Reassessing the geopolitics of rising China

The U.S. secretary of state calls the task of finding more creative and assertive ways of containing China the “mission of our time” for the Western world. The challenge is not going to be easy, as the Chinese Communist Party plays its considerable strengths well.

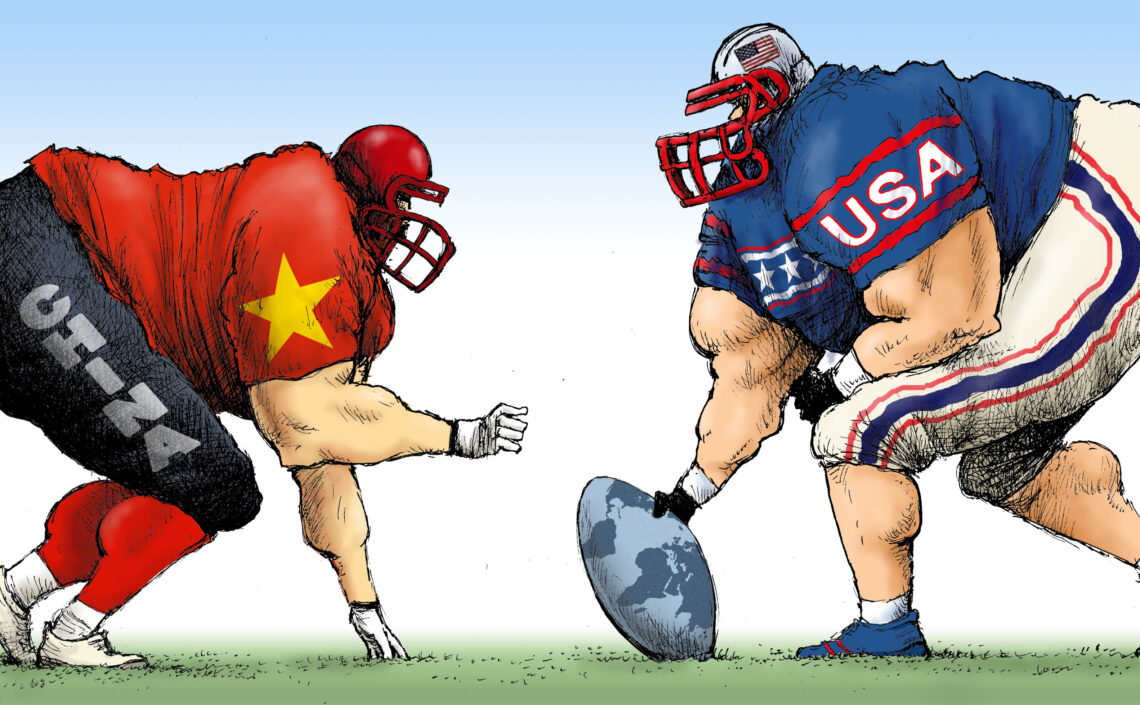

The conflict between China and the United States is intensifying. This is hardly new, as relations between the two countries have been tense for years. Beijing is striving to become a world hegemon and the U.S. strategizes to contain China.

China’s increasing assertiveness has been a source of concern in Southeast Asia. The U.S.’s role as a partner in the effort to contain the new-old giant of the Middle Kingdom is vital to its traditional allies – South Korea, Japan, Taiwan, Australia and the Philippines – as well as other regional actors, such as Vietnam, India and Singapore. All these states feel threatened by Beijing, even though China is also their leading trading partner.

Shows of force

Lately, however, tensions have increased. China’s steady buildup of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), particularly its naval and air branches, has allowed Beijing to try to assert its dominance over the seas adjacent to the mainland. It has drawn sea boundaries disregarding the interests of neighbors such as Japan, the Philippines and Vietnam, and could potentially control all passage through the area. To counter this strategy, the U.S. has now dispatched its most powerful naval force to the South China Sea since the 2017 crisis (when China created military facilities on several contested islands there). Three aircraft carrier groups lead the force. They will conduct naval drills together with U.S. regional allies.

At the same time, the Chinese Navy is intensifying its activities in the waters surrounding Taiwan as verbal assaults against Taipei gain in force. It appears that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), after having brought Hong Kong closer to the mainland, now wants to assert its sovereignty over Taiwan.

Historically, Taiwan has served both as a refuge for anti-communist forces and a symbol of freedom after the armies of Mao Zedong took over mainland China in the 1945-1949 civil war. The small island nation has thrived as a prosperous democracy and a bulwark against totalitarian oppression. Although it is no longer officially recognized by the U.S. since Washington established diplomatic relations with Beijing in 1979, Taiwan remains a close ally.

Many assumed that the Chinese Communist Party, although still authoritarian, had become nonideological after Mao Zedong’s death in 1976.

Last week, U.S. authorities closed the Chinese consulate in Houston, claiming that it was used as a base for espionage. A Chinese citizen was also arrested in California on spying charges. Beijing retaliated by closing the U.S. consulate in Chengdu. U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo declared that Washington and its allies must use “more creative and assertive ways” to pressure the CCP to change its ways. He called the U.S. aim to contain China the “mission of our time.”

The head of U.S. diplomacy directly addressed the role of China’s political regime – a vital aspect of the situation that was largely ignored in the West in past years. Many assumed that the CCP, although still authoritarian, had become nonideological after Mao Zedong’s death in 1976. To drive his point home, Mr. Pompeo quoted President Richard Nixon (1969-1974), who in 1972 paid a historic visit to Beijing that eventually led to formal U.S.-China relations: “President Nixon once said he feared he had created a ‘Frankenstein’ by opening the world to the CCP. And here we are.”

Not simply a Cold War

The secretary emphasized the necessity to build an alliance to contain Beijing, especially with European partners. Brussels and the countries of Europe – with the notable exception of the United Kingdom – have been very cautious to avoid verbally antagonizing Beijing. Their reactions are limited to verbal criticism.

These developments may remind many of the Cold War (1947-1991). Today’s confrontation with China is different but no less dangerous. The notion that China might become more democratic as it grows economically is an illusion. Today’s contest is not over political philosophy: it is a real and potentially bloody power play.

By cultivating its soft power, China has won the support of global institutions.

The CCP does not promote a proletarian world revolution. It uses socialism mainly as an internal control tool. In contrast to the former Soviet Union, China also lacks military allies. Its strategy is a rather extreme variety of “China First,” internally socialist (with all-encompassing state control) and outwardly nationalistic. On the world stage, Beijing aims to become the new hegemon by gaining political and economic influence, which makes it the aim of the U.S. to contain China. Like its emperors of old, the Middle Kingdom appears to consider neighboring countries as tributaries. Beijing’s goal is not to spread its ideology but to grow its influence and control. It pursues this strategy through diplomatic and economic means.

By cultivating its soft power, China has won the support of global institutions. It has also created institutions of its own, like the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, which serves as a tool for economic control. Moreover, some agencies of the United Nations covertly harbor pro-Beijing attitudes. It was hardly surprising that the World Health Organization (WHO) praised China for its handling of the coronavirus outbreak – despite the evidence that Beijing had tried to suppress information on the new disease when the crisis started. The WHO’s recent praise of China could prove overly optimistic.

Beijing resorts to other policies as well. These include financing infrastructure in many countries in Asia, Africa, Latin America and even Europe, as well as strategic business purchases. China continues to establish naval bases in critical locations, such as in Djibouti at the entrance to the Red Sea and, therefore, the Suez Canal. The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), meanwhile, creates a platform for China, Russia, India, Pakistan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan to collaborate. Mongolia, Belarus, Afghanistan and Iran are observers, while Turkey, Sri Lanka, Azerbaijan, Armenia and Cambodia are dialogue partners.

However, China’s most crucial international push is the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the modern-day land and maritime equivalent of the ancient Silk Road. Officially an economic, infrastructure and cultural project, the BRI is thoroughly political. It creates dependencies, only in an indirect, sophisticated way – nothing like the crude Soviet technique of forcing Marxism on other countries through coercion.

The Chinese strategy has a clear underlying ideological component. Due to its size and tradition, the country feels entitled to be a leading nation in the world – at best, the leading nation. It draws lessons from the Soviet Union’s history of failures. The CCP relies on its economy as a pillar of political control and only uses military strength when politics are not enough. Many in the West argue that China has no history of attacking neighboring countries. This is only partially true: Vietnam, for example, experienced several Chinese military interventions over the centuries, the last one in 1979.

There is little doubt that China will use its massive and modern military force as a deterrent to back up its political ambitions. And while it is true that the PLA has little combat experience, as opposed to the U.S. Armed Forces, it would be most unwise to underestimate its strength.

Attempts to change Beijing are bound to fail and shows of weakness can be fatal.

What we are witnessing now is not a confrontation of two well-defined opposing systems, as was the case during the Cold War. We will see global fragmentation, with fewer alliances on China’s side but many effective partnerships. Following this policy logic, China is also trying to establish its own financial and monetary system.

Economy and sovereignty

Understanding China is important, but this does not mean agreeing with its policies. Attempts to change Beijing are bound to fail and shows of weakness can be fatal. Secretary Pompeo’s call to press the CCP to change its ways is warranted. It is essential to curtail China’s interference with other countries’ sovereignty, as well as its unfair trade practices. Unfortunately, protectionism is not only a Chinese habit. Though to a lesser extent, the European Union and the U.S. engage in protectionist practices too.

In this situation, pragmatism is a political necessity. The utopian hope that democracy would spread throughout the world is dead. This makes it only more important for European countries to assess their policies toward China. The goal is not to exclude Beijing but to support other countries’ international order and sovereignty by expanding economic relations. A stronger European commitment to defense is needed too. The Old Continent cannot overtax U.S. generosity in extending the American security umbrella to allies and partners.