Examining Iran’s strengths and weaknesses

Iran has never been both as strong and as weak as it is now. Tehran wields tremendous sway over the governments in Baghdad, Sana’a, Beirut and Damascus. Yet Iran is facing discontent at home and among its neighbors, as protests flare up over its heavy-handedness.

In a nutshell

- Iran has built up a strong regional presence

- However, the government is growing weaker at home

- Economic woes are fanning the flames of social unrest

This report is the third in a three-part series on Iran from GIS Expert Professor Dr. Amatzia Baram. Find the first, on Iran’s leadership structure, here. The second, on Iran’s scenarios for reform and regime change, can be found here.

Since the end of the Iran-Iraq War in 1988 and Ayatollah Khomeini’s death in 1989, Iran has never been so strong and yet so weak at the same time. It is stronger because, as the regime is fond of pointing out, it controls four capitals: Beirut, Damascus, Sana’a and Baghdad. It recently held a joint naval exercise with Russia and China, and almost two years after the United States imposed severe economic sanctions, the Iranian economy has not collapsed, nor is it about to.

Until recently, the U.S., paralyzed by fear of war, had responded meekly to Iranian provocations. Tehran’s bravado had never been more brazen. Following the January 3, 2020, assassination of General Qassem Soleimani, observers understood the tremendous outpouring of grief in Iran as support for the regime.

The assassination also moved some U.S. Democrats and Iraq’s caretaker prime minister at the time, Adel Abdul Mahdi, to send Tehran encouraging messages. The U.S. Congress even passed legislation to try to curb the Trump administration’s power to conduct military action. Prime Minister Abdul Mahdi, following a nonbinding demand from the Iraqi parliament, asked U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo to begin formulating a mechanism for the withdrawal of American troops from his country. All these developments were good portents for Tehran.

Signs of weakness

However, Iran is also weaker than ever. The assassination of General Soleimani, its point man in the region and a critical political player in Tehran, could mean that U.S. President Donald Trump is becoming bolder. Iran’s measured response was an open admission that it recognizes its enormous military inferiority.

The demonstrations in Tehran, Shiraz and Isfahan against the leadership’s lies about the downing of the Ukrainian jetliner were very bad news for the regime. Protesters chanted slogans like: “Death to the murderer,” “Death to the dictator,” “Shame!” “You murdered Iranian citizens,” and “Iran-Chernobyl.” Yet even these were topped by cries of “Liars! America is not our enemy! Our enemy is at home.”

In an astounding scene at the University of Tehran, students walked around the Israeli and American flags painted on the floor so as not to step on them. The regime’s official take is that the demonstrations were an American and Zionist plot. This reveals the cavernous credibility gulf between the leadership and the young generation.

Protesters chanted slogans like: ‘America is not our enemy! Our enemy is at home’.

From the universities, the protest spread to the cultural arena. For example, Gellare Jabbari, a well-known news anchor on state television, resigned. On her web site, read by millions of Iranians, she wrote, “Forgive me for 13 years of lies in the name of the regime. I am joining the demonstrators.” Faezeh Hashemi Rafsanjani, daughter of former President Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, called upon Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei to resign. Many others repeated her sentiments, even though such statements can be severely punished in Iran.

The regime had to resort to using live ammunition (again) to break up the protests. The demonstrators’ persistence shows that even if admiration for General Soleimani as a hero of the Iran-Iraq War is genuine, much of the public has far less esteem for the regime and its brutal praetorian guard, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC).

The most worrisome aspect for Tehran is that these demonstrations, which started back in 2017, are growing more frequent. They are being suppressed with more and more violence as the regime relies increasingly on its guns.

Shocks to the system

The first jolt that rocked the leadership was not an Iranian event. On October 1, 2019, Tehran woke up to a medium-sized demonstration in downtown Baghdad over an internal Iraqi affair, but which eventually had a profound impact on Iran.

The protest concerned the dismissal of Iraq’s most popular general, Abdel-Wahab al-Saadi. His only crime was to be an Iraqi nationalist who resented Iran’s influence over Iraqi politics and security. Most of the demonstrators were Shia, revealing the anger against Tehran within that community. The protests spread quickly across the country, with demonstrators decrying corruption, government ineptitude and high unemployment. The blame for these ills was laid at Tehran’s door. The most concise and widespread anti-Iranian slogan became “Iran barra, barra”: “Iran out, out.”

Probably the most symbolically significant events were attacks by protesters against the Iranian consulates in the Shia Islam holy cities of Najaf and Karbala. General Soleimani ordered the Iraqi security forces to put down the protests at any cost. The army declined but the pro-Iranian Hashd militias killed between 400 and 500 demonstrators and wounded thousands. To no avail – the demonstrations continued. Even despite the threat of coronavirus, the hard-core protesters are still demonstrating in Baghdad’s Tahrir Square.

Facts & figures

The second jolt that rocked Tehran was the October 17 demonstrations in Lebanon, which were partially inspired by the protests in Iraq. Similarly to Iraq, while anti-corruption and anti-sectarian, these demonstrations were also anti-Hezbollah and in a more muffled way, anti-Iranian. The Lebanese, too, despite Hezbollah’s semi-violent attempts, refused to stand down. While smaller, street demonstrations are also still occurring in Beirut.

However, Tehran was most worried about the way the protests in Iraq evolved. Not only were they fiercely anti-Iranian but they also united the country under a sizable proactive element that was entirely Shia. The Sunnis, for their part, for fear that they would be identified with Islamic State, were passive supporters. The Kurdish president refused to collaborate with the Iranians and the other Kurds kept very quiet.

Those developments were a particularly bad omen for Tehran, due to Iraq’s geographic proximity and the Shia-versus-Shia nature of the protest. Moreover, Iraq provides Iran with net income. Holding sway over the other governments – in Lebanon, Syria and Yemen – results in net expenditures for Iran.

Al-Sistani steps in

To add insult to injury, the Najaf-based Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, the leading Shia authority in the world, supported the demonstrations from the very beginning in the summer of 2018 and did not waver even after protesters set fire to the Iranian consulate in Basra. When the protests erupted again in October 2019, Ayatollah al-Sistani called for the resignation of Iran-backed Prime Minister Abdul Mahdi, for a new electoral law and new elections.

The prime minister was forced to resign, even though General Soleimani had ordered him to ignore the ayatollah’s demands. Worse, Iran applied all the pressure it could to appoint pro-Iranian Governor of Basra Asaad Al Eidani as prime minister. Ayatollah al-Sistani opposed the move and President Barham Salih threatened to resign. The nomination fell through. Later, another pro-Iranian candidate was also rejected.

The prime minister was forced to resign, even though General Soleimani had ordered him to ignore the ayatollah’s demands.

By late December, the demonstrators had declared a boycott on Iranian products. Iran’s annual exports to Iraq are worth about $9 billion. If it succeeds, the boycott will represent a problem for the Iranian economy. By mid-March 2020, the anti-Iranian demonstrations continued, despite about 550 killed and 30,000 wounded. The assassination of General Soleimani made it politically more difficult to demonstrate, but not enough to end the protests.

The coronavirus pandemic did not end the demonstrations either, even though it reduced the number of participants. Still, due to the closure of the universities, many students joined. The protests now are mostly aimed at the government for the miserable state of the health infrastructure and lack of coronavirus reporting, and against the Iranians, who are pouring into Iraq and spreading the disease. The most fervent demonstrators say that if the regime’s guns did not deter them, the coronavirus certainly will not. Protesters are providing free masks and disinfectant and are checking people’s temperature.

Fuel-price hike

Tehran’s concern about Iraq and Lebanon proved justified. The next blow came in mid-November 2019, in response to a late-night announcement that gasoline would be rationed and that prices would rise by 50 percent. Protests started in the northeastern holy city of Mashhad and, thanks to social media, spread to more than 100 cities, towns and villages throughout the country.

The speed at which the demonstrations proliferated, the unprecedented vitriol and vandalism that typified them, and the mix of social classes that took to the streets surprised the Iranian leadership. Hundreds of banks, government buildings, petrol stations and other symbols of the regime were set ablaze. Ayatollah Khamenei’s portraits were burned with great fanfare. Demonstrators shouted, “forget about Palestine, we have no money,” and “no Syria, no Lebanon, no Iraq.” They even chanted, “Bring back the shah,” “Death to the dictator,” and “Death to Khamenei.”

With this, they had crossed a red line. The Supreme Leader ordered his security branches to do “everything necessary” to quash the uprising. He was also deeply worried because, unlike in 2009, most of the demonstrators were not middle-class young people and university students, but rather blue-collar, low-income workers. Moreover, the demonstrations had erupted in many periphery cities. In other words, these were the people that had formed the regime’s core popular support. It may be said that for the first time since its founding, the Islamic Republic was attacked by the very people for whom Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini claimed to have led his revolution: al-mustad’afin fi al-ardh, or “the oppressed in the land.”

The regime claimed that about 200 had been killed in the violence, and that it had detained about 7,000 people. Opposition groups and international media put the number of people killed by the police emergency forces, the Basij militia and the Revolutionary Guard at some 1,500. The number of wounded, detainees and disappearances was in the many thousands.

Economic woes

The Supreme Leader had good reason to be worried. The Iranian economy is malfunctioning partly because of its structural problems and partly due to the U.S.-imposed embargo. The protests were an expression of genuine frustration. This frustration was further aggravated by the sense that the nation’s wealth – especially its petroleum riches – was being plundered by the privileged few.

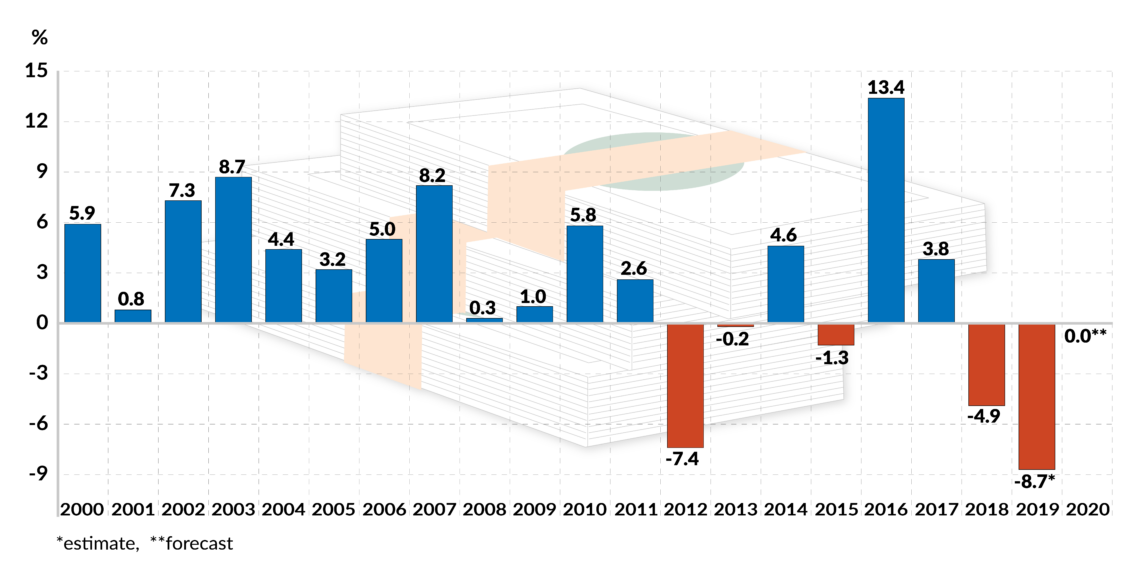

According to the World Bank, Iran’s gross domestic product (GDP) shrank by 8.7 percent in 2019, and will likely see no growth this year. The population is increasing by 1 percent annually, which means that the per capita GDP is likely to continue its decline.

By 2019, oil exports had declined from 2.5 million barrels per day to around 400,000.

In 2018, Iran’s per capita GDP was $5,400, as compared to around $9,300 in Turkey, which has no oil or gas. Inflation in mid-2019 was at least 40 percent. The individual citizen felt it more acutely on a daily basis because prices for vegetables, milk and chicken increased by 70 percent. If one is living on a very modest salary, such price hikes are shocking.

By 2019, oil exports had declined from 2.5 million barrels per day to around 400,000. Iran is managing to evade the oil embargo somewhat, but not on a large enough scale. According to both U.S. and Iranian sources, the sanctions have cost Iran some $200 billion. The recent decline in oil prices is further eroding Iran’s oil revenue.

Before the coronavirus crisis, unemployment was officially about 12 percent but unofficially among the young it is twice as high; among educated young people the rate is some 40 percent. By mid-March, it may have increased by 50 percent. Tourism died out and domestic trade must have declined precipitously.

The same thing has happened around the world, and Iran legislated a support package for 3 million needy families, but it does not have the economic reserves needed to further cushion the effects of the crisis in the future. The Iranian banks are severely restricted because they are mostly cut out of the international financial system.

The government’s annual budget is around $43 billion. At least 30 percent of the budget (some say 50 percent) had previously been covered by oil and gas revenues. These revenues have now shrunk by at least a half. Even after raising gasoline prices, the fuel is still about 20-percent subsidized. The government is hard-pressed to reduce subsidies across the board and increase taxes. Will the poor accept such policies?

Ayatollah Khamenei recently coined the expression ‘Resistance Economy’ in hopes that the suffering masses will identify their travails with a lofty cause.

Ayatollah Khamenei recently coined the expression “Resistance Economy” in hopes that the suffering masses will identify their travails with a lofty cause: the struggle against the U.S., the Zionists and the Saudis. It is clear from the 2019 disturbances that the poor were not impressed. They consider their suffering the result of government corruption, inefficiency and the privileged position of certain segments of society. The students in 2020 have showed that they are not impressed either.

The coronavirus crisis represents the most recent blow. Official statistics state that by mid-March, about 1,000 had died and 16,000 had been infected. Reports on social media indicate that the true numbers may be at least twice those figures. At least 12 senior politicians and officials have died and some 20 more are infected. The government closed down the holy shrines in Qom and Mashhad, but people in the latter city flaunted the restrictions.

The partial curfew is not working. Tehran’s airport is still quite active; flights are leaving mainly for Najaf (pilgrims, militias), Turkey, Beirut and Damascus (military, pilgrims). Health services for most people are almost nonexistent. Add the half-hearted public response to the hodgepodge government policy, and we can understand the Health Ministry’s frustration. Its spokesperson told the public that if they obey the government’s instructions only 12,000 Iranians will die, but if they flaunt them 3.5 million will. Regime spokesmen accuse the U.S. of bringing the virus to the country. There are no demonstrations, but all the signs are that the credibility of the regime has hit rock bottom.

What needs changing?

When he came into office in August 2013, President Hassan Rouhani tried to introduce some economic reforms. He wanted to double gasoline prices, cancel financial entitlements for millions of people and introduce some streamlining in other segments of the economy. His rivals forced him to withdraw his proposals.

Now, under the pressure of the U.S. embargo, they have agreed to a single step: raising gasoline prices. The Supreme Leader himself gave the move his full support, though he insisted on shielding the privileged segments of society that support him. To ease the economic pressure, President Rouhani must do much more.

Further reducing subsidies is one necessary step. Even just the November 2019 partial increase of gas prices will save the Iranian treasury more than $5 billion annually, between direct savings and eliminating the smuggling of subsidized petrol abroad. President Rouhani will have to increase taxes on the upper-middle class and rich, reduce all or most of the privileged groups’ financial entitlements, eliminate all of the bonyads (independent charity funds) that benefit the clerics and the IRGC, introduce radical measures to crack down on official corruption, and appoint decent professionals to manage the economy and infrastructure.

Any such reforms will serve as ammunition for his opponents. The middle and upper-middle classes vote in droves, while the working class does not.

When it comes to national security, Iran is spending a few billion dollars annually on Syria, Lebanon and Yemen – in that order from most to least. The decision to drastically cut the regime’s financial commitments there is above the president’s pay grade. The same applies to a decision to accept American demands to engage in new nuclear negotiations. It seems unlikely that the more powerful decision makers will further reduce security expenses abroad substantially.

If they cannot wait for the U.S. elections in November, it seems that the Iranian leadership’s choice will be either a military escalation or renewed nuclear negotiations. The public’s trust in and support of the regime is now at its lowest point ever. The hope that hostilities will unite the masses around the leadership may tilt the Iranian regime’s decision toward more aggression, either direct or through its proxies.

However, this unprecedented and very dangerous crisis could serve as a golden opportunity for President Rouhani to implement the deep reforms he always wanted.