Iran’s stakes in Syria

While Iran is not responsible for the outbreak of the Syrian civil war, Tehran has exploited the situation to its advantage. Iran has injected tens of thousands of pro-regime fighters into the country, keeping President al-Assad in power.

In a nutshell

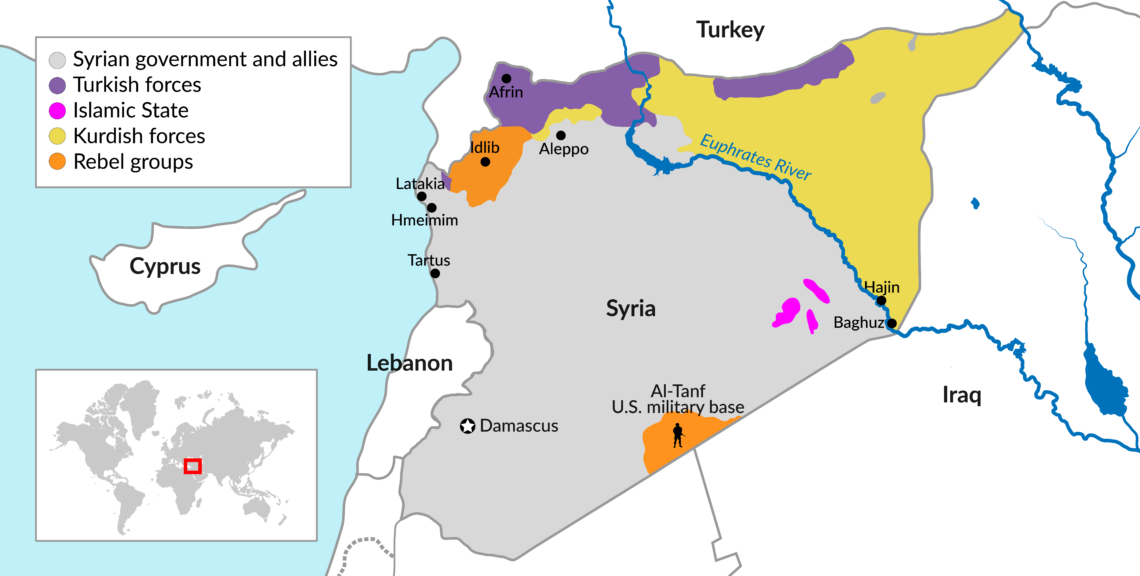

The territory that was Syria until March 2011 is, as of the fall of 2021, ruled by five powers and two embryonic states. The northwestern coast is controlled by Russia. The northwest is ruled by Sunni jihadists. The north is occupied by Turkey and could soon be annexed. The northeast, from the Euphrates River to the Iraqi border, is a Kurdish protectorate maintained by the United States. The border zone with Lebanon is Hezbollah territory.

The center, center-north and the south, roughly two-thirds of what was Syria, is ruled by a military coalition. One component is President Bashar al-Assad’s army. It consists of the Russian-commanded Syrian Fifth Army (a division size), of the Iranian-controlled Syrian Army’s Fourth Division, and other units. Another component is Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), and there are also three Iran-backed Shia militias. At the juncture of the Iraqi and Jordanian borders in the south, there is a small American enclave at Al-Tanf.

For Iran, while Iraq serves as a cash cow, Syria is a net loss in financial terms.

In the central and eastern deserts, President Assad’s coalition and the Kurds occasionally fight Islamic State. U.S. forces in Syria are also sometimes attacked by pro-Iranian Iraqi militias.

In 2011, there were between 21 and 22 million Syrians. Ten years later, at least 400,000 people have died in the civil war, and more than half the Syrian population has fled the country or become internal refugees. Many Sunni Arabs have been pushed out of areas controlled by the regime, where an incremental Iranian demographic, cultural and Shia colonization is underway.

Economic hardship

Just before the outbreak of the civil war, the Syrian economy had been hard-hit by a few years of drought – one of the causes of the conflict. But the war brought with it an unmitigated economic disaster. The World Bank estimates that already by 2018, about a third of Syria’s housing and half of its health and education facilities had been destroyed. Reconstruction will cost at least $300 billion and take at least 10 years.

There are also external obstacles to rebuilding Syrian society. In response to the al-Assad government’s atrocities and corruption, in June 2020 the U.S. passed the Caesar Syria Civilian Protection Act, which sanctions businesses and individuals with connections to the regime’s economic enablers. The broad scope of the measures has scared off foreign investors. Gulf countries are unwilling to invest in reconstruction also because of the overwhelming Iranian presence. Finally, the banking disaster in Lebanon froze the assets of many Syrian entrepreneurs.

In 2010, the Syrian gross domestic product (GDP) per capita was low – $2,380 – but by 2019 it had halved. Between January 2011 and January 2021, the black market Syrian lira deteriorated from 50 to at least 3,500 liras per $1. Most of the population sank into poverty. By 2021, over 80 percent of the territory’s inhabitants fell below the poverty threshold.

As salaries lost most of their value, security personnel have been compensating themselves by privately “taxing” Sunni and Kurdish entrepreneurs in the provinces. New warlords and pro-Assad and pro-Iranian militia as well as local army commanders are oppressing the local Sunni population there. In 2020, the government reduced food and petrol subsidies while also imposing strict rationing. By early 2021 bread and fuel were in short supply and there were long queues even in Damascus and the Alawite region, leading to sporadic protests. An Amnesty International report from September 2021 states that the few Sunni refugees who returned were severely harassed.

Gradual colonization

For Iran, while Iraq serves as a cash cow, Syria is a net loss in financial terms. Some oil revenues from the east and some from commercial assets are dwarfed by the huge investment required to maintain the Iranian military presence and civilian entrenchment. According to knowledgeable sources, the decade of involvement in Syria cost Iran around $100 billion.

Even if the cost is half that, for a country under embargo this is an enormous expense. However, in the long run, these costs could bring strategic gains. Syria is the gateway to Lebanon, to Hezbollah and to the Mediterranean, which are all crucial to Iran’s long-term plans. Furthermore, the tomb and mosque of Sayyidah Zaynab, sister of Imam Hussein, in southern Damascus is a crucial site in the Shia world. Since 1990, Iranian mass pilgrimages to the tomb have been a feather in Tehran’s cap.

In September 2015, the London-based, Arabic-language newspaper Al-Quds Al-Arabi published excerpts from the book “I Know Them at Close Range,” authored by Saqr al-Milhim, an ex-diplomat from Hafez al-Assad’s era now living in exile.

From 1997 to 2002, Mr. al-Milhim served at the Syrian embassy in Tehran as a mid-level diplomat, eventually becoming fluent in Farsi. His analysis of the inside workings of the opaque Iranian regime is revealing.

He describes a meeting in Tehran immediately after Hafez al-Assad passed away. Iranian officials came to express their condolences. A group of senior military officers was also in attendance. They spoke Farsi, believing that no Syrians would understand their language. The most senior officer spoke to his people very quietly, saying: “Allah removed the mountain from our path. Soon Zaynab will wake up from her slumber and our ships will sail again on the Mediterranean.”

Bashar al-Assad fails to appreciate the threat that radical Shia Iranian nationalism poses to his secular Arab Syria.

The “mountain” referred to Hafez al-Assad, who had opposed excessive Iranian interference during his rule. Mr. al-Milhim’s report, if authentic, demonstrates the Iranian leadership’s hybrid soul, combining religiosity with a cold interpretation of Iran’s strategic interests. The report rings true; after Hafez al-Assad’s death, nothing has stood in Tehran’s way. Bashar al-Assad, writes Mr. al-Milhim, turned Syria into “Iran’s thirty-fifth district.”

The fast-moving civil war that broke out in March 2011 rattled Tehran. In April and May, Iranian leaders provided the al-Assad regime with riot-control equipment and trained them in intelligence monitoring techniques, as well as Iranian intelligence and cyber officers. In late 2011, the deteriorating situation forced Iran to send special forces to save the president. The number of IRGC and Iranian army troops in Syria reached around 15,000.

In 2012 Hezbollah fighters crossed the border from Lebanon and took over eight villages in the Al-Qusayr District. Ever since, their involvement has been considerable, at first only in the Syrian territories bordering on Lebanon but eventually all over. In 2013 Iran began sending Iraqi, Afghan and Pakistani militias into Syria to replace the Iranians, and soon most of the Iranian troops were withdrawn. By 2015 the number of Shia militiamen reached tens of thousands.

Still, President al-Assad’s military was disintegrating. In July 2015, Iran made a desperate move. IRGC Quds Force Commander General Qassem Suleimani paid an emergency visit to Moscow and urged the Russians to save the regime. In exchange, President al-Assad agreed to allow Russian bases on the Mediterranean.

Despite all its investments, Tehran could not single-handedly save President al-Assad. Russia charged into Syria full steam ahead, but not as a full-fledged ally of Iran – rather as a “frenemy.”

By the end of 2020, Iran and its subordinate militias had 131 military sites in Syria, scattered through 10 districts. Since 2011, the Iranians and their allies have been gradually taking over in parts of Damascus but also Aleppo, Hama, and the south. In many areas, they acquired real estate abandoned by Sunni refugees who will never be able to return. Families of the Shia Afghan, Pakistani and Iraqi militiamen are being settled there.

Facts & figures

In large cities and in the southeast, a growing number of Alawites but also some Sunnis are converting to Shia Islam. Iranian cultural institutions and holy sites are serving as hybrid conversion and recruitment centers for pro-Iranian local militias.

All this is leading to a gradual but profound “Shiafying” of Syria. With more than half the Syrian population, almost all of them Sunnis, unable to return to their homes, this process will soon be irreversible. Maybe Bashar al-Assad considers the newcomers more loyal to him than the cleansed Sunni Arabs. If so, then, unlike his father, he fails to appreciate the threat that radical Shia Iranian nationalism poses to his secular Arab Syria.

Iran’s most ambitious strategic project in Syria so far is a strategic railway connecting the Persian Gulf with the Mediterranean through Iraq. The political, military, and economic implications of such a railway are immense. The project will harm Baghdad’s political and economic interests as it further subjugates its economy (not to mention its politics) to Tehran’s. Worse, it conflicts with an immeasurably more beneficial project linking Egypt and Jordan with Iraq within a common economic system – the New Levant Project. Iraqi Prime Minister Mustafa Al-Kadhimi, his reluctance notwithstanding, will agree to the Iranian project. However, the U.S. and Israel will do what they can to derail the initiative. Russia, too, will be wary of such massive Iranian infrastructure in Syria. It is not clear yet what China’s position will be, but the railway would possibly compete with the Belt and Road Initiative.

Tehran’s responsibility

Iran is not to blame for the outbreak of the Syrian civil war. Climate change and the initial oppressive steps taken by the Assad regime against the Sunni population of southern Syria had nothing to do with Iran. However, very soon after the civil war erupted Iran began exploiting the civil war to its advantage.

By injecting tens of thousands of pro-regime fighters into Syria, compensating for the incremental disintegration of Mr. al-Assad’s military, Iran empowered itself at the president’s expense. By allowing its forces to perform atrocities alongside those performed by the regime, Tehran also legitimized President al-Assad’s crimes and encouraged him to persecute the Sunni majority in Syria. By taking advantage of the mass flight of Sunnis to entrench themselves in large areas of Syria, Iranians have capitalized on the plight of the Syrian people. Crucially, Iran’s presence in Syria is also preventing Gulf countries from investing in reconstruction.

That Iran’s involvement in Syria is prolonging the suffering of most Syrians means little to Tehran.

Russian commitment to the al-Assad regime has been no less solid than Iran’s and Russian forces were no less brutal than the Iranian ones. But Russia has never tried to colonize Syria as Iran has done. Unlike Iran, it has also made extensive diplomatic efforts to settle the Syrian conflict. At the beginning of the civil war, in the February 2012 UN-sponsored negotiation, Moscow was even ready to drop Mr. al-Assad as part of a political solution. For Iran, the weak Bashar al-Assad is indispensable.

Scenarios

The Russians have also been trying to persuade President al-Assad to change the constitution and allow more or less free elections. Iran has never joined this effort. The Kremlin hopes for an end to hostilities. It would no longer need to send Russian soldiers into battle, and its strategic presence on the northern shore would be under less threat from Islamist groups. If a more legitimate regime approved Russian bases, they would also receive more international approval.

Russia understands that a compromise would win Turkish support and thus remove a dangerous friction point between Moscow and Ankara. If such an outcome also marginalizes NATO, then all the better. For Iran, however, any such compromise would mean less influence and an eventual evacuation of troops from Syria. To stay entrenched, Iran needs to do very little, only support President al-Assad’s staunch opposition to an agreement with the Sunni rebels or rapprochement with Turkey.

That Iran’s involvement in Syria is prolonging the suffering of most Syrians means little to Tehran. Religious and ideological convictions paired with strategic calculations make the regime impervious to any humanitarian considerations. Iranian leaders need Syria. If they need to run it into the ground to remain in control, they will.