Israel’s unlikely coalition soldiers on, but for how long?

After two years of political turmoil and four unsuccessful attempts at forming a viable government, Israel finally has a ruling coalition. A wide range of parties came together, motivated by the shared goal of ousting long-reigning Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

In a nutshell

- Israel’s motley coalition is fragile

- The Arab party could opt out in a security conflict

- The arrangement could last if hurdles are overcome

After two years and four inconclusive rounds of elections to the Knesset – Israel’s parliament – a government was finally sworn in on June 13, 2021. It faced a hard task: restore stability and confidence in the political system. From 2019 to 2021, then-Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, chairman of the Likud party, repeatedly tried to form a coalition with right-wing and religious parties, as he had done in the past. However, he was unable to muster the 61 Knesset members out of 120 he needed to form a sustainable coalition. It was a tense period, with civic movements and parties on the left taking to the streets to demand his resignation.

Unlikely coalition

Mr. Netanyahu, in power since 2009, was facing charges of bribery, fraud and breach of trust. Though he denied the charges and the Supreme Court had ruled that he was under no obligation to step down while his trial was ongoing, opposition groups demanded that he do so on moral grounds. For more than a year, large demonstrations were held not only in front of his residence but also on bridges and major roads throughout the country, leading to violent clashes with his supporters. The public mood was angry, fueled by heated debates in the press and on television.

Even the right side of the Israeli political spectrum, a Netanyahu stronghold and dominant electoral bloc, was affected. Gideon Sa’ar, a leading member of the Likud party, defected to set up a new formation, New Hope, declaring he remained faithful to the right but would not take part in a Netanyahu government. Avigdor Lieberman, head of the secular, nationalist Yisrael Beiteinu party, also said he would no longer be part of a coalition based on the religious parties that had traditionally backed Mr. Netanyahu. Even Naftali Bennet, head of the right-wing Yamina alliance, abandoned his erstwhile ally.

One of the most bizarre aspects of the situation is that the government is led by Naftali Bennett.

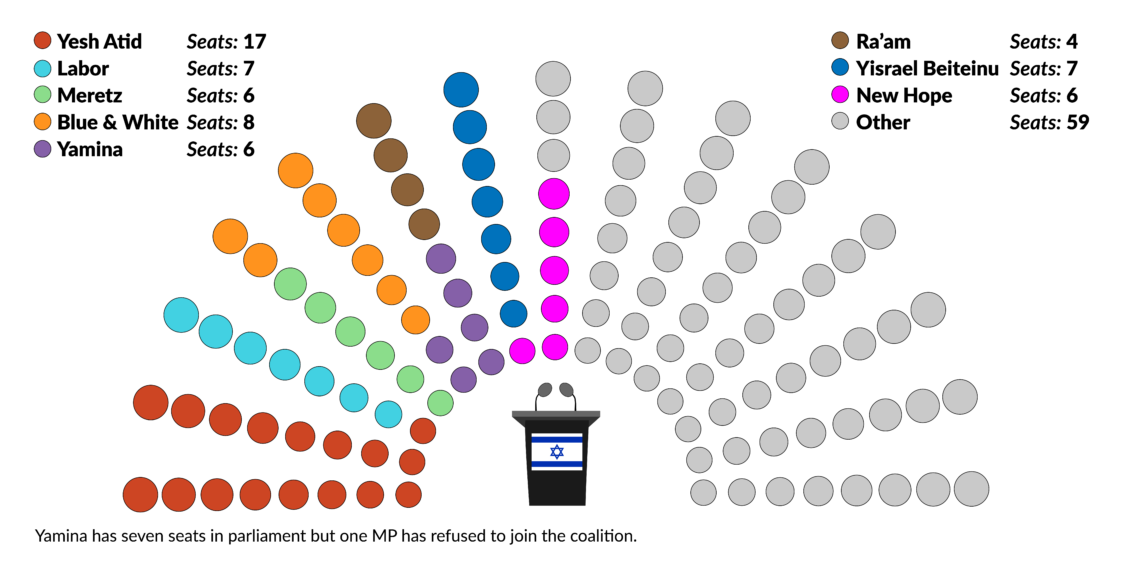

The fourth election brought no solution to the political divide – neither side received a majority of the vote. But people hoped that their representatives would make the necessary sacrifices to form a government urgently needed to deal with pressing health, economic and security issues. Against all odds, an unlikely coalition was born, uniting eight parties ranging from the far left to the far right, as well as, for the first time, an Arab party, Ra’am. Their vastly diverging ideologies were bridged by a common goal: obtaining the required majority and preventing a Netanyahu comeback at all costs. The government was confirmed by the Knesset by the narrowest margin, 60 against 59, one of the members of Ra’am abstaining. This shows how fragile the coalition majority is, leaving it open to pressure by individual members.

To satisfy each of its components, the new government is one of the largest the country has known: 27 ministers and deputy prime ministers, nearly half its representation in the Knesset. Out of necessity, the new leaders made exceptional use of the so-called “Norwegian Law,” which enabled a third of the ministers to resign from the Knesset to focus on their duties and allowed the next candidates on the party list to take their seats. Under this arrangement, if a minister wishes to resume his or her seat, the substitute must give it back.

Two prime ministers

One of the most bizarre aspects of the situation is that the government is led by Naftali Bennett, whose Yamina party has only seven Knesset members, and not Yair Lapid. Mr. Lapid is head of Yesh Atid, which with 17 members in the parliament is the largest coalition faction. As such, Mr. Lapid who was tasked by then-President Reuven Rivlin to form a new government after Benyamin Netanyahu had failed to form a coalition government despite Likud’s 30 seats.

However, it was obvious from the beginning that he would be unable to achieve a coalition with leftist and centrist parties as he would have liked. He would need to get the support of two right-wing parties, Yamina and Yisrael Beiteinu, with rigid principles such as rejecting the creation of a Palestinian state, as well as one Arab party, Ra’am. To achieve this apparently impossible feat and realize his ambition to promote a change of government, Mr. Lapid let Mr. Bennett take the coveted leadership spot for the first two years of the Knesset’s four-year term. Mr. Lapid will be foreign minister until 2023, at which point he will switch roles with Mr. Bennett.

Facts & figures

As things stand, the eight parties making up the coalition are the centrist Yesh Atid and the Blue and White alliance, the right-wing New Hope and Yamina, the nationalist and secular Yisrael Beiteinu, the leftist Labor, the far-left Meretz and the conservative Islamic Arab Ra’am, which has links to the Muslim Brotherhood. This is a historic precedent on many counts. On one hand, it is the first time Israeli Arabs have been included in a government; but Ra’am will have to accept measures against Palestinians dictated by security imperatives. It could quit and trigger the fall of the government if there is an armed conflict with Hamas or any other Palestinian movement. But this would defeat its purpose in joining the coalition: ensuring reforms and bigger budget outlays for the Arab minority in Israel.

The coalition was achieved after arduous negotiations. The talks had to be halted for 11 days while Israel responded to a Hamas missile attack on Jerusalem, which threatened the fragile agreement.

The new government’s program focuses on economic issues – passing a budget and implementing reforms. Guidelines on sensitive topics such as relations with the religious sector and the Palestinian conflict are vague. The Israeli Arab community will receive a much greater portion of the budget and the government will make fighting violence in that community a priority. Some of these worthy objectives will probably remain empty declarations.

The vulnerable coalition will need responsible leadership not to lose sight of its main goals – surviving to the end of its four-year mandate to restore stability, pass much-needed laws and implement indispensable reforms, all the while maintaining the delicate balance between its component parts. It will also have to deal with a relentless opposition spearheaded by Benjamin Netanyahu, who branded Naftali Bennet a traitor who “stole” votes from the right.

Impressive record

Three months on, the coalition has surmounted several obstacles and remains whole. It has agreed on most of the legislative projects and economic reforms that were stuck in limbo and has drafted a budget for 2021-2022. Faced with a Hezbollah attempt to draw the country into an armed conflict by launching rockets on the Galilee region for the first time in years, the government replied swiftly and decisively.

Prime Minister Bennett engaged in fruitful talks with Jordan. The United Arab Emirates opened an embassy in Tel Aviv and Foreign Minister Lapid flew to Abu Dhabi for the inauguration of the Israeli Embassy there. He also met in July with the foreign ministers of the European Union in a move to convene the 1995 Association Agreement that had been put on hold after Operation Protective Edge in 2014. Altogether, this is an impressive record. However, if the coalition cannot get the Knesset to pass the budget by November as required by the constitution, the government will fall, and new elections will be held in 2022.

Riots broke out in mixed Jewish-Arab communities, leaving deep scars.

Meanwhile, Israel is battling an upsurge of the Delta strain of Covid-19, which hit the country hard after a successful vaccination campaign initially appeared to have nearly eradicated the virus. Prime Minister Bennett took the bold step of not imposing a new lockdown, which would have been disastrous for the economy, instead promoting booster shots. The strategy seems to be working, earning the government kudos.

Like his predecessors, Mr. Bennett faces several significant challenges. During the operation to respond to the missile attacks, riots broke out in mixed Jewish-Arab communities, leaving deep scars. At least some of these riots were incited by Hamas.

Violence is on the rise in the Arab community where gang warfare, vendettas and so-called “honor killings” have already claimed 94 victims in 2021 – including 11 women and numbers are expected to rise before the end of the year. The police have been given a bigger budget and more personnel to tackle the problem. Ra’am approves of the move in principle, though it is ready to pounce if it believes that excessive force is being used.

In line with its conservative agenda, the Arab party voted down a law legalizing private use of cannabis and opposes the pro-LGBT policies favored by the Meretz and Labor parties. Mr. Lieberman’s goals include public transportation on the Sabbath, compulsory teaching of core subjects in religious schools and allowing civil unions. Meretz and Labor support this agenda, but Yamina and New Hope oppose it; they still hope to convince the more moderate religious parties to join the coalition. There are other divisive issues, but these have been put on hold out of a tacit agreement to preserve the coalition.

On the international front, the main concern is the Iranian threat and its impact on relations with the United States. Israel needs to convince the Biden administration that there is no point in going back to the old agreement, since Tehran has made great strides toward the nuclear bomb.

Scenarios

Jerusalem has been careful not to comment on the hurried withdrawal from Afghanistan. But it is worried that Washington is retreating from the Middle East, leaving Israel to act alone should Iran be on the brink of producing a nuclear weapon.

Ahead of a visit to Washington in late August, Prime Minister Bennett had reportedly prepared suggestions for an alternative policy entailing heavy pressure on Tehran by Israel and the Gulf states with strong backing from the U.S. There were talks of a blueprint for secret operations to damage Iranian nuclear installations. In the briefing he held after meeting the Israeli prime minister, President Joe Biden did state that he would never let Iran develop a nuclear weapon, adding that “if diplomacy fails we are ready to turn to other options.” This positive result strengthened the position of Mr. Bennett and his government.

There was no breakthrough on the Palestinian issue. Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas has rejected every proposal – including former President Donald Trump’s “Deal of the Century” – without proffering a plan of his own

Hamas has increased its influence in the Palestinian territories. Israeli forces must be present there not only for Israeli security but also for the Palestinian Authority. They alone prevent infiltration by Iranian agents and terror organizations. Nevertheless, Ra’am could yet opt out in case of serious clashes with Hamas.

The coalition is at the mercy of the defection of one of its components. Its success is not guaranteed. Former opponents who came together to defeat Mr. Netanyahu may feel pressured by their constituents and become restive. As of now, decisions are being taken by Prime Minister Bennet and alternate Prime Minister Lapid. It has been suggested that a representative of the left be included in some of the deliberations to ensure that a consensus is reached in time to prevent a crisis.

Should the government overcome this hurdle and get Knesset approval for the budget – by no means a given – the new ministers could come to believe that they can advance their agendas without giving up their core beliefs. The coalition would then last through its term. Should a major external threat emerge from Iran, Hamas or Hezbollah and demand decisive action, it would probably lead to the formation of a unity government with all parties, as in the past.