Lebanon and Israel’s historic maritime border deal

The decision to agree on their maritime borders will benefit Israel and Lebanon, but it remains to be seen whether the region can become a natural gas hub.

In a nutshell

- The U.S.-brokered agreement solved a decade-long dispute

- The deal will allow hydrocarbon exploration to proceed

- Despite this progress, the region still faces hurdles as an exporter

After more than 12 years since major natural gas discoveries in the Levant Basin in the Eastern Mediterranean, the region has come to a historic understanding. In October 2022, Lebanon and Israel agreed to solve their maritime border dispute under the mediation of the United States. The White House swiftly congratulated both parties, stating that “the region and beyond will soon reap the benefit of these energy resources that will advance security, stability, and prosperity.”

Maritime disputes are common but challenging. By 2020, more than half of all maritime boundaries in the world were still disputed. Solving such conflicts can easily take decades, even between friendly neighbors. For Israel and Lebanon, which have no diplomatic relations and are officially at war, reaching a deal within a relatively short time is a major achievement.

The agreement has removed a major hurdle to exploiting the region’s hydrocarbon potential, primarily by lowering the political risk for investors and potential customers alike. Many analysts now predict that the Eastern Mediterranean could play an important role in helping Europe find alternative gas suppliers to Russia. European Union documents state: “Israel, Egypt and Cyprus, because of their significant offshore gas reserves, make the Eastern Mediterranean region a strategic partner for the EU in its effort to diversify its gas supply routes.” Lebanon could also be added to the list if it makes substantial discoveries.

Facts & figures

However, that optimism may be overdone. The Lebanon-Israel resolution alone is unlikely to be a game changer for the region; several obstacles remain. Persistent effort and consistent policies are still needed to create a reliable gas hub in this politically fragmented region.

Timeline of the dispute

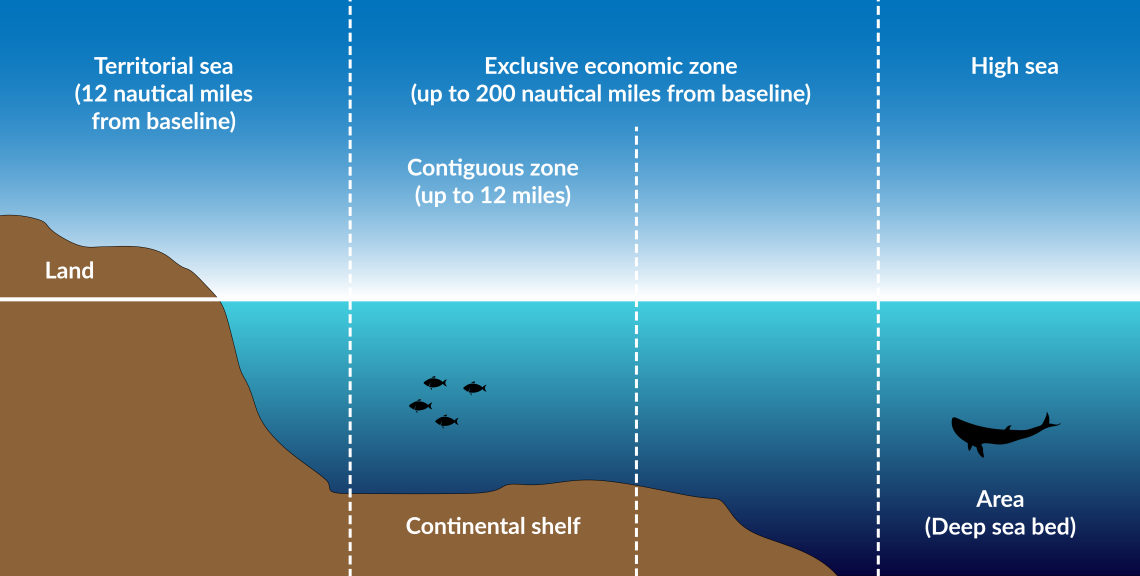

The maritime border dispute between Lebanon and Israel emerged in the first decade of the century when countries in the region started to conclude agreements delimiting their economic exclusive zone (EEZ) to exploit offshore natural resources like oil and gas.

Facts & figures

Exclusive economic zones

First, Cyprus and Egypt agreed on their mutual EEZs in 2003. Then in 2007, Lebanon and Cyprus signed an agreement delimiting their maritime borders. The deal included one clause that left open the possibility of amending the southernmost and northernmost borders of the EEZs in case of future agreements with neighboring countries, namely Israel and Syria.

This open clause complies with the United Nations Law of the Sea, but it also has a political dimension. Beirut likely did not want to jeopardize its relationship with Turkey, which complained that the deal violated the rights of Northern Cyprus. Lebanon was still reeling from the devastating war between Israel and Hezbollah in July 2006 and was still in the middle of a domestic political crisis. Although Cyprus ratified the deal in 2009, Beirut has yet to ratify it.

In July and October 2010, Lebanon presented the geographical coordinates of its EEZ at the office of the UN secretary-general, stretching the EEZ further.

In December 2010, Israel signed an agreement with Cyprus delimiting their EEZs while taking into consideration the coordinates of the 2007 Lebanese-Cypriot agreement. However, according to Lebanon’s 2010 claim, the end of the Lebanese EEZ was 17 kilometers further. These conflicting claims created an overlap of nearly 860 square kilometers, where some of the country’s offshore southern oil and gas blocks are located.

In July 2011, Lebanon submitted a letter to the UN reaffirming its 2010 claim – Line 23 – which was then rejected by Israel.

In 2012, the U. S. offered to mediate between the two. One proposed solution was to split the disputed area by a line, called the Hoff line, into 490 square kilometers for Lebanon and 370 square kilometers for Israel. Neither of the disputing parties agreed to the proposal and the negotiations stalled.

Historic agreement

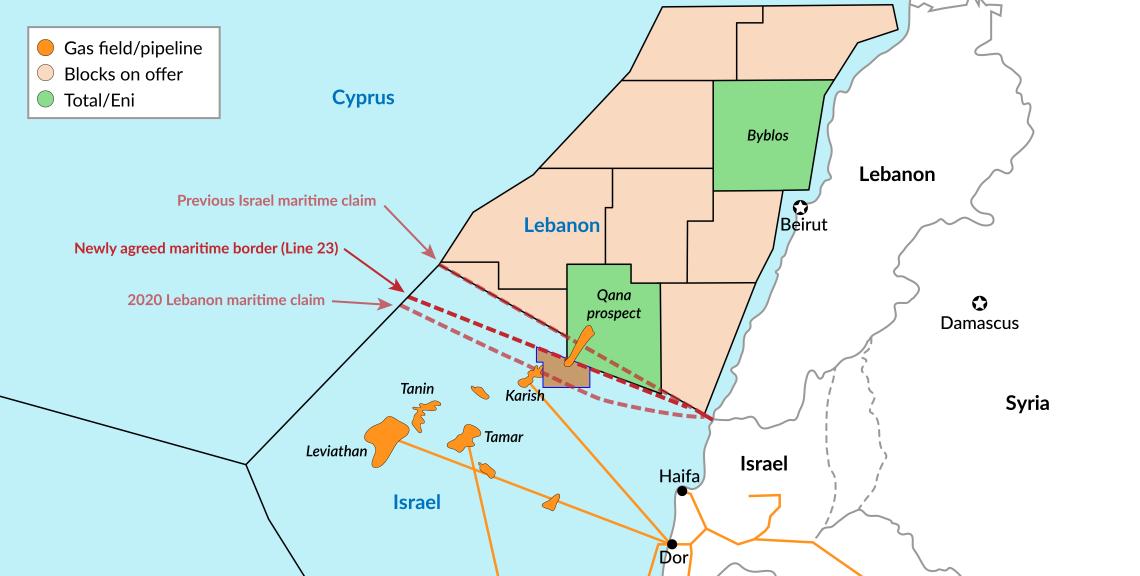

In October 2020, talks were reinitiated, facilitated once again by the U.S. Meanwhile, Lebanon submitted a new claim supported by one study conducted by the United Kingdom’s Hydrographic Office and another by the Lebanese Army. The country further extended its maritime boundary southward, adding 1,430 square kilometers to the disputed area of 860 square kilometers. The newly claimed boundary would directly cross Israel’s Karish gas field, due to start producing gas in 2022.

After almost two years, a deal was signed on October 27, 2022. The agreement stipulated that Line 23 would be the final line dividing the two EEZs. Furthermore, Israel received full rights to explore the Karish field. Meanwhile, Lebanon received full rights to the Qana prospect – an area that geologists believe may contain hydrocarbons based on seismic surveys – but agreed to allow Israel a share of royalties through a side agreement with the French company TotalEnergies for the section of the field that extends beyond the agreed maritime border.

Facts & figures

Exclusive economic zone claims in the Mediterranean Sea

Understandably, there was no joint signing ceremony. Still, both parties emphasized the political benefits of the deal. While former Lebanese President Michel Aoun emphasized that the accord did not constitute a peace agreement with Israel, describing the deal as purely technical, he added that the accord would prevent war with Israel and that the full status of the southern border would be resolved later through dialogue.

Meanwhile, Israel’s prime minister at the time, Yair Lapid, portrayed the deal as a political victory, stating that “it is not every day that an enemy country recognizes the state of Israel, in a written agreement, in view of the international community.”

The road to stability

The solution has cast some optimism on the political outlook of the region, thereby reducing the security and political risk for investors and potentially attracting capital inflows. For the heavily indebted Lebanese economy, this could even reverse the vicious downward spiral the country has experienced particularly in the last few years. In 2021, the World Bank described the economic crisis in Lebanon as “one of the top 10, possibly top three most severe economic collapses worldwide since the 1850s.”

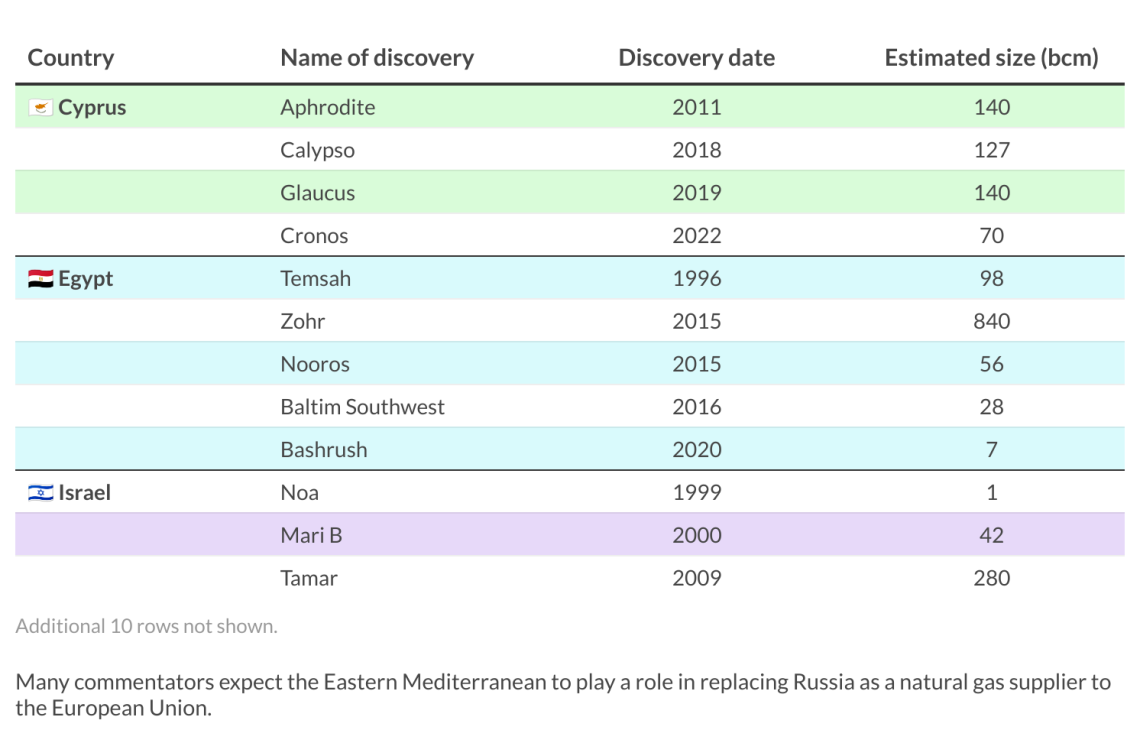

Furthermore, if the presence of hydrocarbons is confirmed in the Qana prospect, Lebanon – where no discoveries have been made so far – will become significantly more attractive to energy companies. To date, most discoveries in the Levant basin have been made in Israel as well as in Cyprus, albeit smaller volumes. Only Israel has been producing natural gas and exporting a small fraction to Egypt.

The timing is also favorable. Lebanon launched its second licensing round in November 2021; it was originally due to close in December 2022, but the deadline has been extended to mid-2023 to take advantage of oil companies’ record profits.

Should discoveries be made in Lebanon, they can first be used domestically to alleviate and potentially solve Lebanon’s chronic power shortage problem. Additional supplies can be exported, bringing in much-needed foreign currency to the country.

Facts & figures

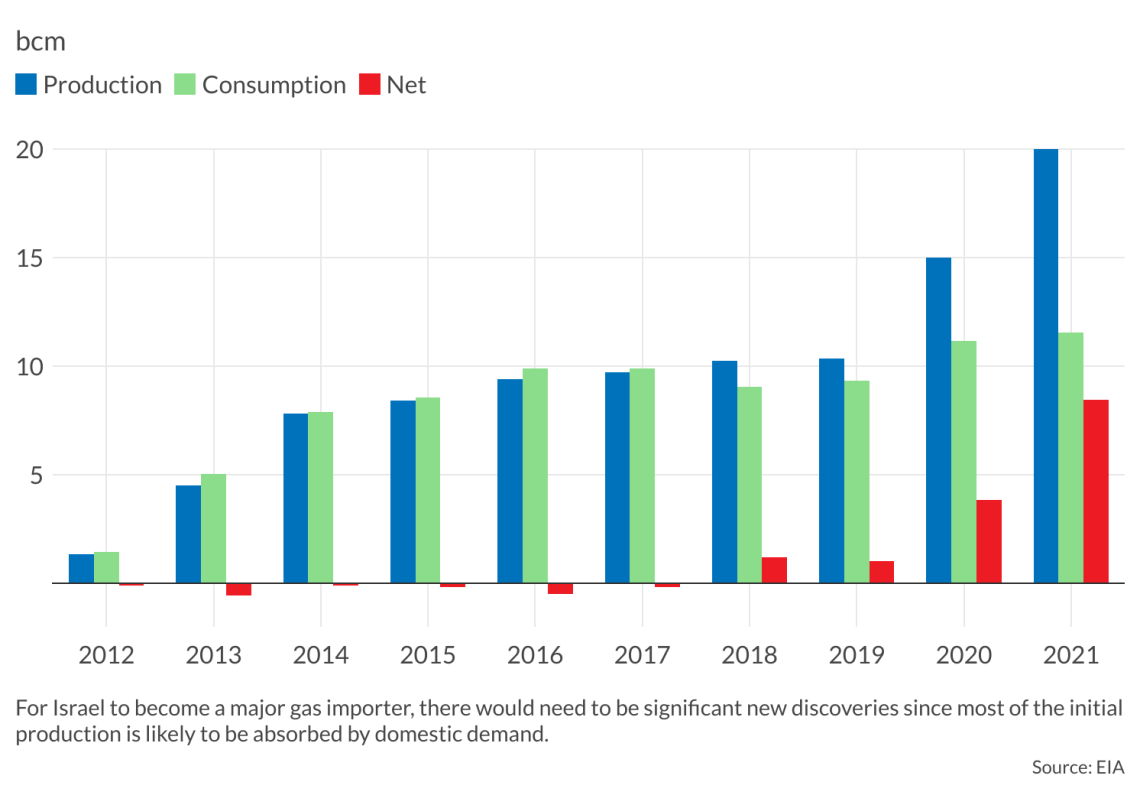

Israel has already gone down that path. Its gas production initially prioritized the local market, largely displacing imported fuels, mainly coal. In 2012, the Israeli administration decided to cap gas exports at only 40 percent of potential reserves to guarantee domestic supply for the next 25 years. In 2021, a surplus of 8.5 billion cubic meters of Israeli gas was exported partly to Jordan and partly to Egypt, either for local consumption or contributing to the country’s own LNG exports. Production from the Karish field is unlikely to dramatically change Israel’s export capacity.

From a purely economic perspective, Lebanon needed the deal much more than Israel. From a security perspective, however, both parties are equal winners. The White House described the deal as “equally beneficial to both Israel and Lebanon, it will strengthen the economic and security interests of Israel, while promoting critically needed foreign investment for the Lebanese people as they face a devastating economic crisis.”

Facts & figures

- The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) of 1982 is the globally recognized regime dealing with all matters relating to the law of the sea. Turkey, Israel and Syria have not ratified the UNCLOS.

- The Levant Basin encompasses approximately 83,000 square kilometers of the easternmost portion of the Mediterranean, stretching from Israel to northwest Syria, and including Lebanon and Cyprus.

- Lebanon’s energy and electricity mixes are largely dependent on imported petroleum which meets more than 90% of the country’s energy needs. These imports also account for nearly 30% of the country’s total merchandise imports.

- In 2019, Egypt, Jordan, Palestine, Israel, Cyprus, Greece and Italy launched the East Mediterranean Gas Forum (EMGF), a cooperation platform headquartered in Cairo. It received political backing from the U.S., the EU and several international institutions.

- The Tamar and Leviathan gas discoveries offshore in Israel in 2009 and 2010 respectively were described as the two biggest gas discoveries of the decade.

- In December 2019, Turkey and Libya reached a maritime deal that creates an EEZ running from Turkey’s southern Mediterranean shore to Libya’s northeast coast. The deal has been condemned by Greece, Cyprus and Egypt.

Scenarios

The deal is a milestone in the East Mediterranean region’s quest to become a major supplier in global gas markets. However, on its own, it is far from being sufficient. More discoveries need to be made to boost the export potential of the region, bearing in mind domestic market needs.

But depending on their location, some discoveries may prove problematic. There is no guarantee that, in the case of a discovery extending between Lebanon and Israel, an agreement would automatically be reached on the revenue-sharing mechanism. And there is precedent in the region even between two players on good terms. Aphrodite, Cyprus’s largest gas discovery to date, remains stranded more than 10 years after its discovery as it extends into Israel’s EEZ. The two parties could not agree on the extent to which Israel has rights in the field.

Political risk could also hinder further developments. Notable politicians in Israel continue to oppose the deal, including Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, and so do some voices in the Lebanese parliament.

The Eastern Mediterranean region still has many maritime borders to be delineated, including between Lebanon and Syria, Syria and Cyprus, Turkey and Cyprus, as well as between Turkey, Greece, Egypt and Libya.

On balance, while there is good reason to praise the remarkable progress that has been achieved to date, the quagmire of the Eastern Mediterranean’s gas is far from being over. Placing too much hope on the region’s export potential continues to be a risky bet. For Lebanon in particular, clinging onto highly hypothetical revenues instead of pursuing much-needed economic reform is a very dangerous bet.