Japan’s new outreach in Asia

China’s rise as an economic and military colossus has transformed the geopolitics of East Asia. Its most powerful neighbor, Japan, has embarked on a more self-reliant course, even as it continues to lean heavily on its alliances with the United States.

In a nutshell

- China has challenged Japan’s preeminence and aloofness from Asia’s mainland

- In this new situation, the country has an unusually strong leader in Shinzo Abe

- The prime minister is vigorously promoting reengagement with Asian allies

China’s rise as an economic colossus has had an enormous impact on the geopolitics of Asia. Recently, the world has woken up to the new military and security challenges posed by this ascendant and self-confident superpower. China’s most powerful neighbor, Japan, has embarked on a more self-reliant course in defense and diplomacy. While it continues to lean heavily on its close alliance with the United States, Tokyo is expanding its contacts, both economic and strategic, with Southeast Asia, India and Australia.

Uneasy neighborhood

Some years ago, at an after-dinner discussion on Japan’s position in East Asia and the world, an eminent Japanese historian exclaimed: “We are not Asians, the Indians and Chinese are Asians. We are Japanese!” Indeed, as an island nation, Japan has traditionally had a complex and sometimes difficult relationship with the Asian mainland. In many ways, its behavior mirrors how the British interact with Europe.

There can be no doubt that continental Asia has had a decisive impact on Japanese culture and civilization. Particularly ubiquitous is the influence of China and Korea, from Buddhism to kanji script, from traditional city planning and architecture to food and agriculture, from pottery to painting and music. In many ways, Japan’s most distinct characteristic is how it improved upon whatever it borrowed from its neighbors. The specific Japanese identity is one of refinement and aesthetics.

While, like every island nation, the Japanese are a mixture of ethnicities, the extended archipelago has never been occupied and conquered by a continental Asian power. In the 14th century, when the Mongols occupied the imperial throne in China, there were attempts by expeditionary forces to land on the islands. However, nature in the form of mighty typhoons kept the potential invaders away. In the late 19th century, developments took a different turn.

While China, India and most of Southeast Asia were humiliated and conquered by the Western imperial powers, Japan decided to change history and modernize its economy, society and institutions to resist foreign powers. The Meiji Restoration turned Japan into Asia’s most advanced industrial nation. Within half a generation, Tokyo built the most powerful military in East Asia. Japan defeated China in the First Sino-Japanese War in 1894-1895; 10 years later, it was Russia’s turn to suffer defeat by Japanese arms.

The Meiji Restoration is perhaps the most successful example of crash modernization in history.

The Meiji Restoration is perhaps the most remarkable example in history of the successful crash modernization of a whole nation. However, it also fed the hubris of Japanese imperialism, which brought war and destruction to most of Asia and led to Japan’s humiliating defeat and occupation by the Americans at the end of World War II – the first time this island nation had come under foreign rule in recorded history.

This trauma led to a comprehensive rejection of militarism and war, enshrined in Article 9 of Japan’s postwar constitution (drafted by its U.S. conquerors). As a result, Tokyo based its national security on an American security guarantee, backed by treaty and embodied to this day by substantial U.S. military bases in the archipelago.

Freed from the burden of maintaining large armed forces, Japan could focus on rebuilding its devastated industrial base into one of the most advanced and efficient in the world. Compared with this achievement, Communist China remained a marginal economic and military power. Until the beginning of the 21st century, the Japanese were reasonably confident that they would remain the preeminent power in the Far East.

Wake-up call

All this has changed. In the late 1970s, Deng Xiaoping initiated his first economic reforms; for the next three decades, China’s economic rebirth was impressive but, from Tokyo’s point of view, manageable. Looking back, it is evident that the turning point was China gaining access to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001. Soon enough, its economic ascent looked unstoppable. Over the past 10 years, Beijing has accumulated by far the largest foreign exchange reserves ever held by a single country, and in 2011, the People’s Republic of China overtook Japan as the world’s second-largest economy. The latter development came as a rude shock to Japan.

The tectonic shifts have become more far-reaching and more substantive in recent years. While Deng Xiaoping, a wise and historically conscious statesman, had admonished his country to “hide its strength” and “bide its time,” since the rise of Xi Jinping to the highest positions in the country and the party in 2012-2013, China has become more assertive in its neighborhood and on the world scene.

There is growing concern in Tokyo about unpredictable U.S. foreign policy and its geopolitical implications.

With the administration of U.S. President Donald Trump, things have taken a new turn. On the one hand, Washington has become close to belligerent toward Beijing, reacting not only to massive distortions in bilateral trade but also to China’s growing military strength and expanding strategic reach. On the other hand, there is growing concern in Tokyo about the unpredictability of U.S. foreign policy and particularly about the geopolitical implications of MAGA (“Making America Great Again”). Tokyo is aware that the “new” U.S. demands much greater defense outlays from its allies, not only in Europe and NATO but also in the Far East. Equally, there are new doubts in Tokyo about whether Washington will stand by Japan’s side in all eventualities, especially in the dispute over the Senkaku Islands in the East China Sea.

Abe’s uniqueness

Since it capitulated to the allies in August 1945, Japan has had no less than 28 prime ministers and 55 governments. Longevity was obviously not a hallmark of Japanese cabinets. In contrast to the frequent personnel changes, the governance structure has been very durable. The Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), formed in 1955 through the merger of two conservative parties, has been in power for no less than 58 of the past 64 years. Constant leadership changes and the electoral strength of the LDP has meant that the international profile of Japanese politicians and the significance of foreign policy on the domestic political scene have been marginal.

Occasionally, there were prime ministers who were exceptions to this rule, such as Kakuei Tanaka (1972-1974), Yasuhiro Nakasone (1982-1987) and Junichiro Koizumi (2001-2006). Perhaps the most remarkable is Japan’s current head of government, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, who has held office since 2012 and whose current term runs through 2021. If he stays the course, he will become postwar Japan’s longest-serving prime minister.

Whether by lucky coincidence or design, Japan is being led by a man with no serious rivals within his own party or the opposition precisely at a moment when the country has lost its regional preeminence. In response to the Chinese challenge, Mr. Abe has developed a great affinity for foreign policy and security issues, which has given him an unusual prominence in international affairs. Critics of the prime minister have accused him of abetting nationalism and warmongering. However, it would be truer to say that he has made the Japanese realize they can no longer stand aside while a new world (dis-)order emerges, as they were content to do throughout the Cold War period.

Southern pivot

This extensive background is required to appreciate just how fundamentally Japan’s position in the world has shifted, particularly in Asia. The changes have both economic and security implications. After some initial reluctance, Tokyo has taken notice of Chinese economic expansion into Southeast Asia, the Indian Ocean region, the Middle East, Africa and even Europe – most strikingly through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), whose geopolitical implications are profound.

If more proof for China’s global ambitions were needed, it was provided by the launching of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) in early 2016. This new multilateral institution, in which China holds the veto power, is a useful instrument for expanding Beijing’s influence and curtailing that of the Bretton Woods institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, which have traditionally been dominated by the U.S. and the Western industrialized nations.

Under Shinzo Abe’s leadership, Japan has begun to face up to the challenges posed by China’s ascent.

Until now, China has not used war to expand its zone of influence, though it is using military methods to stake territorial claims to the South China Sea by a series of faits accomplis. Beijing’s central tool to enhance its position in the world and challenge the supremacy of the U.S. is the economy. More and more countries in Asia, Africa and Latin America have been targeted for Chinese investments, trade and bilateral economic cooperation. In many cases, these countries have run up sizable debts to Chinese lenders, fostering one-sided dependency or even vassalage.

Under Shinzo Abe’s leadership, Japan has begun to face up to these challenges. Tokyo has considerably increased its economic cooperation with members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and India. It has also increased its financial stake in the Asian Development Bank, an alternative to the AIIB and traditionally an institution under Japanese leadership. Japanese corporations have expanded their presence in Southeast Asia and India. Projects and investments range from infrastructure to manufacturing and information technology.

As countries grow wary of the debt trap and overdependence on Chinese capital, and as China becomes more aggressive in promoting its economic and geopolitical interests, many Asian nations have welcomed Japan as a regional counterweight. Most recently, we have witnessed turnarounds in Malaysia and the Maldives, where resentment of Chinese arrogance has grown.

Scenarios

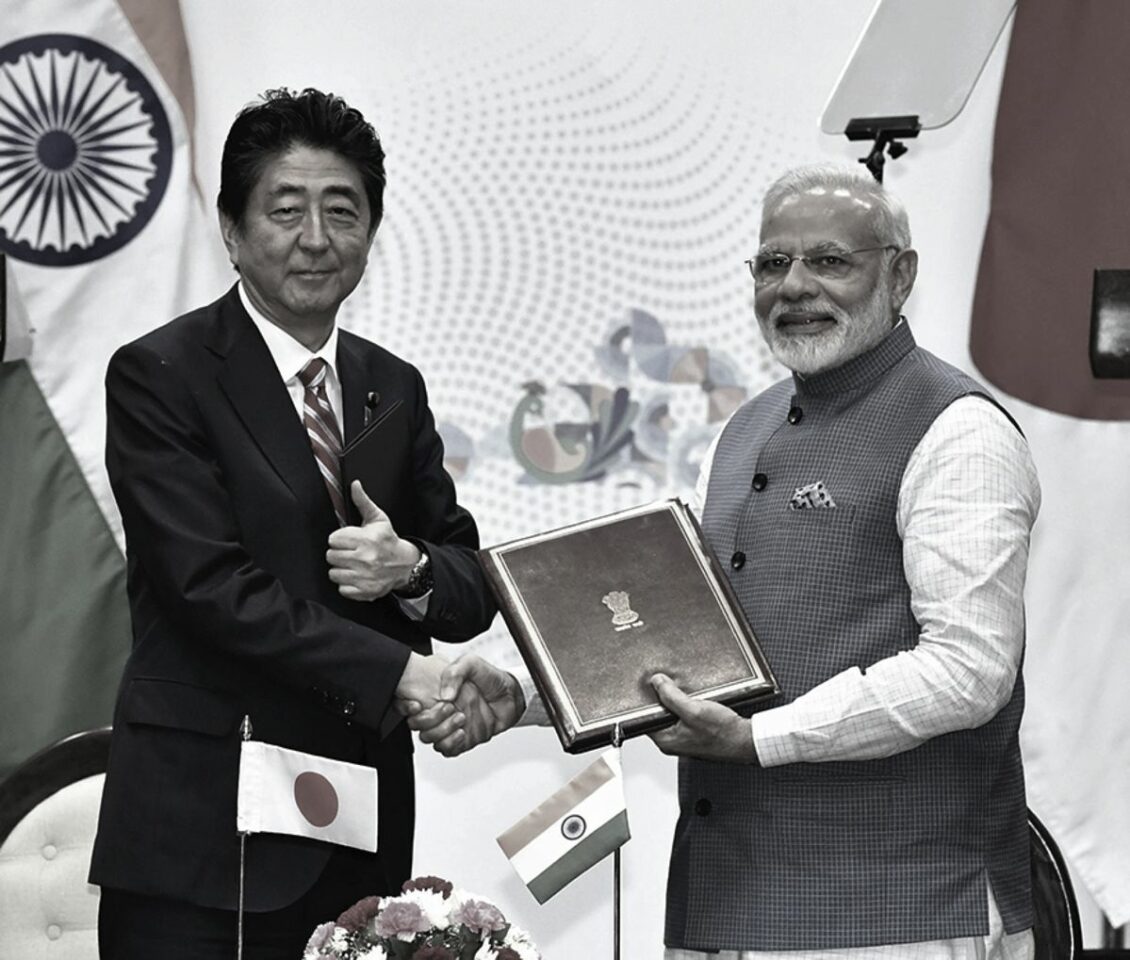

Japan's commitment to Asia will deepen and widen in the years to come. As the country works to raise its international profile, its main effort will be channeled through diplomacy, security cooperation and investment. Mr. Abe himself has been relentless in promoting Japan. He has established an excellent rapport with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, and the two meet regularly.

The Japanese navy has been substantially upgraded in recent years, and it has begun to venture far beyond home waters. Cooperation with other navies is increasing, most notably with the Australian and Indian fleets. Japanese companies have carried on their expansion throughout Southeast Asia and India. In part, this business strategy has been dictated by the shrinkage of Japan’s domestic market due to a rapidly aging society, and in part it reflects new geopolitical priorities in Asia.

Much closer cooperation can be expected with those ASEAN nations – notably Indonesia, Malaysia and Vietnam – that are most worried by Chinese expansion. The Sino-Japanese rivalry over Myanmar will intensify, but here Beijing has the advantage due to geography, culture and history. Tokyo will pay more attention to Taiwan, as this island will become one of the main points of friction in East Asia in the years to come. Furthermore, to protect its vulnerable supply lines to Europe and the Middle East, Japan will take a greater interest in the Indian Ocean and show its flag more there.

Even so, Japan’s reengagement with Asia will show a much lighter touch than China’s. Beijing’s approach has been to solidify its presence through port management, landing privileges, outright infringement of economic sovereignty or even the establishment of overseas military bases (Djibouti). Tokyo has neither the interest nor the ability to adopt this hegemonic approach. Its instruments will be diplomacy, soft power, and inducements for closer economic and strategic cooperation. The result will be an intensified, but asymmetric, regional rivalry with China.

Recent overtures by the Chinese leadership to involve Japan in the BRI project will not go beyond the talking stage. While Japan certainly shares China’s concerns about American protectionism and trade wars, its core interests strongly diverge from Beijing’s. Occasional discord between the U.S. and Japan should not obscure the core reality that when it comes to national security, the Japanese will depend on the American defense umbrella for a very long time to come.