Realism overtakes wishful thinking in Japan

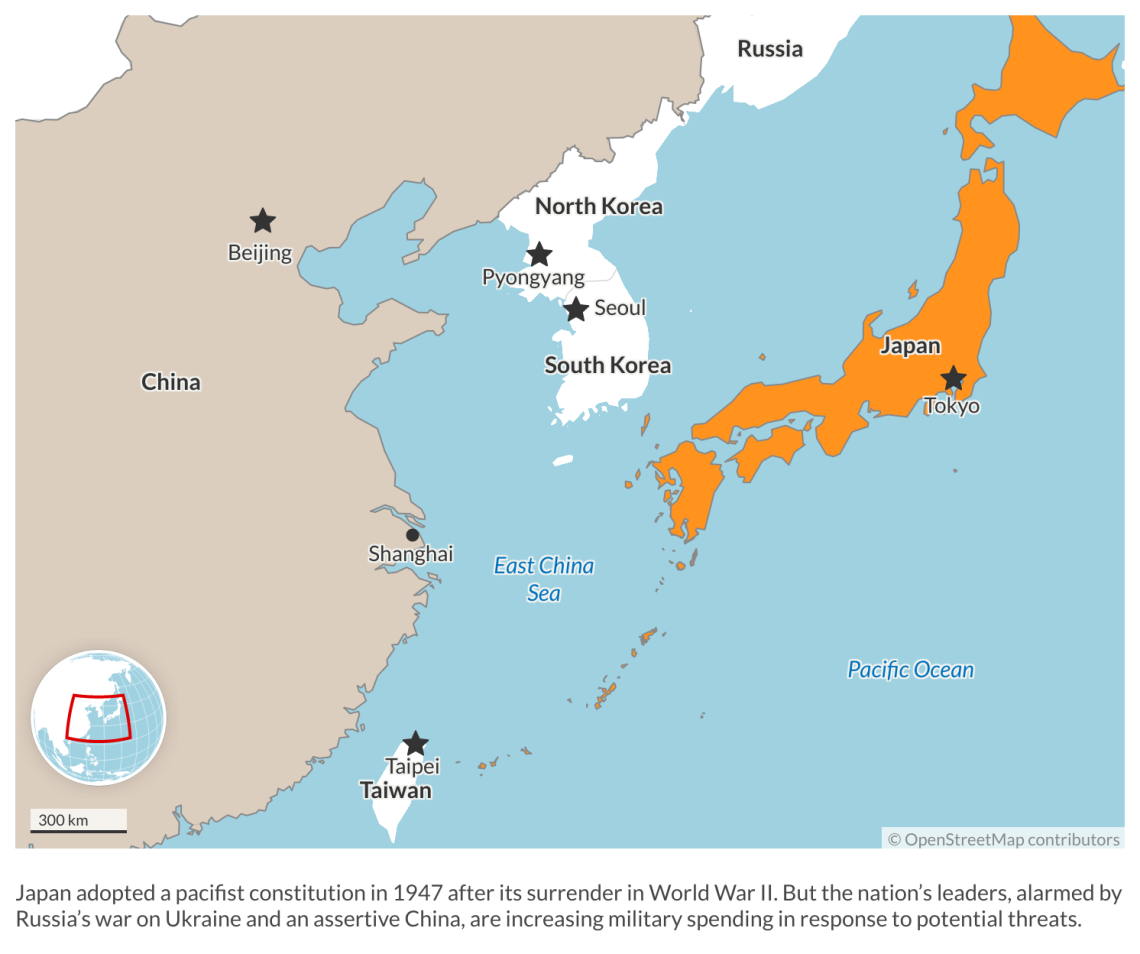

With China and North Korea making aggressive moves, Japan is awakening to the need for increased defense spending and reassessing its post-World War II pacifism.

In a nutshell

- Japan will seek to double annual defense spending by 2027

- Its new security strategy loosens restrictions on military activity

- Some Japanese worry a tougher posture will endanger peace

The world is facing the most significant and turbulent geopolitical shift since the end of World War II. While the West is understandably focused on the war in Ukraine, far-reaching readjustments of military strength and influence are taking place in East Asia. These changes not only herald a new age in conflict and security but are part of a trend toward Asia’s preeminence in global politics.

Throughout the past three decades, the world was focused on issues of globalization and supply chains. In the new world shaping up, the key issue will be how evolving geopolitics will affect the world economy. In this, China and the United States are crucial. The U.S. is, for the foreseeable future, the only Western power on an equal footing with China. It is not out of altruism or concern for allies that Washington is refocusing its China policy. It is simply a reflection of the fact that the U.S. is a Pacific power and thereby, unlike the Europeans, an Asian stakeholder.

Many Western analysts see the challenge posed by Beijing as an ideological issue. This is certainly a factor, particularly since the rise of Xi Jinping to the pinnacle of the Chinese Communist Party. However, there is also a strong element of the classical power game, which had once been pursued by the German Reich during the 30-year rule (1888-1918) of Wilhelm II, with his striving for a “place in the sun.” This ambition is at the core of Beijing’s drive for global grandeur, with which Japan’s 126 million people must contend. It is a remarkable turn of history that some 100 years ago, Japan itself was in search of a “place in the sun.” Tokyo’s answer was imperialism, which brought great harm to China and Southeast Asia.

There are several reasons that led Japan to the disastrous choice that ended in its humiliating capitulation on August 15, 1945. Japan, like Germany, was a latecomer in the game of imperialism. It was concerned about getting its share of overseas colonial possessions. Once it started its empire building, the vulnerability of its supply lines of vital materials and resources was exposed as a major threat. An American embargo led Japan to launch its attack on the U.S., thereby initiating the Pacific theater of World War II. Remarkably, Chinese concerns about Washington are similar today.

Read more by Urs Schöttli

Multitasking for Japan’s strategists

Anxious look to Taiwan

Japan is witnessing a similar conundrum with Beijing’s security policy, most notably its aggressiveness in the South China Sea, the East China Sea and the Taiwan Strait. During the high tide of globalization, Japan – like its Western partners – harbored the illusion that China would be satisfied with acquiring economic might. Tokyo believed – or at least acted as if it believed – that the changes initiated by market-oriented reformist Deng Xiaoping, who ruled from 1978 to 1989, would transform the People’s Republic.

Berlin and Tokyo now face threats that both were able to ignore during most of the post-World War II era.

In the late 19th century and early 20th century, Japan, like Germany, suffered from latecomer syndrome. In both cases, this ended in catastrophic defeat. Under active tutelage by the victorious U. S., both countries decided to abandon military strength as a tool for national greatness. In Japan, this ended in a pacifist constitution that in its remarkable Article 9 prevents Tokyo from active overseas military engagements.

In Germany and Japan, the shift in focus to economic development and reduced military spending relied on U.S. deterrence of any threat. The rapid post-World War II ascent of Japan and Germany, respectively the world’s third- and fourth-largest economies, was aided by meager military budgets that did not reflect the real security threats. With Russia’s all-out invasion of Ukraine, the security environment has become more dangerous. Berlin and Tokyo now face threats that both were able to ignore during most of the post-World War II era.

Japan’s neighborhood has always been dangerous, particularly due to the unpredictable regime of Kim Jong-un in Pyongyang, with his huge nuclear and missile ambitions. North Korea, however, does not pose the same challenge to East Asia as a war between the Chinese mainland and Taiwan. A shooting war in the Taiwan Strait would have a devastating impact on the world economy, particularly if the U.S. were drawn into it.

Taiwan is close to Japan’s Okinawa archipelago. It is almost inconceivable that a war would not involve Okinawa and thereby the Japanese self-defense forces – even more so as nationalist forces in Beijing do not consider the islands, formerly known as the Ryukyu Kingdom, as a part of Japan. The return of Taiwan, the “renegade province,” to the motherland is the sacred duty of every leader in Beijing. Repeatedly, President Xi has stressed that reunification could be achieved through military force if necessary.

All this bodes ill. A glance at the maps of Southeast and East Asia shows a cordon sanitaire established by the U.S. around the Pacific coasts of China. It must be broken if Beijing wants to be a superpower on par with Washington. And in this cordon sanitaire, Taiwan and the Japanese archipelago are key elements. We recall General Douglas MacArthur’s description of Japan as the “unsinkable aircraft carrier.”

Facts & figures

Kishida will follow in Abe’s footsteps

The painful realization that Japan needed to enhance its military security had begun to sink in several years before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Although President Donald Trump had an exceptionally good relationship with Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, he made it clear that Japan, America’s most important ally in Asia, had to substantially increase its military budget. He even indicated that Tokyo may not completely rely on American involvement in a war defending, for example, the Senkaku Islands in the East China Sea. President Joe Biden has, instead, emphasized America’s role as a reliable Japanese ally.

Mr. Abe, who retired as prime minister in September 2020 and was assassinated last year, was the longest-serving prime minister since World War II. He also left an important legacy internationally. He realized that the changing security environment demanded not only an increase in military hardware but also a much wider role for Japan in the world.

Mr. Abe wanted the Japanese to understand that, for their own security, the nation needed to invest more in their defense and remove pacifist impediments. Japan also had to enhance its contacts and cooperation with countries like Australia, India, Indonesia, Vietnam and Taiwan – all nations with concerns about the aggressive rise of China.

The message to Beijing is clear: An invasion of Taiwan would lead to an escalation of unforeseeable dimensions.

Upon being chosen by the Diet, Japan’s parliament, to become prime minister, Fumio Kishida made it clear that he would follow in Mr. Abe’s footsteps. Mr. Kishida pursues a more subdued leadership style than his flamboyant mentor. This trait may work in his favor, as the outspoken Mr. Abe created a lot of adversaries.

One thing seems clear: Prime Minister Kishida will not dominate Japan’s political scene as Mr. Abe did during his almost nine years at the helm. Mr. Kishida must operate in an environment that, since the outbreak of Russia’s war against Ukraine, has become much more dangerous. He has a clearer perception of the risks that China poses to Japan. An ever-larger part of the Japanese public shares the opinion that China, as described in Japan’s new National Security Strategy, presents an “unprecedented strategic challenge.”

Japan’s changing strategy

Since 2013, when Japan’s last National Security Strategy came into effect, President Xi’s rise has increased the perceived threats in Tokyo, bringing Japan closer to the U.S. position.

A new National Security Strategy published last year envisages the doubling of Japan’s defense budget, the ninth-largest in the world in 2021, with annual spending of $80-$90 billion over the next five years. There are still political debates about how to finance this extra burden and, equally important, how to implement the new defense strategy.

Japan’s vulnerabilities are underscored by Chinese missiles landing in Japan’s exclusive economic zone near Taiwan, Chinese transgressions into the waters around the Senkaku Islands in the East China Sea and North Korea firing ballistic missiles over Japanese territory.

All these violations have demonstrated that Tokyo cannot prevent itself from military engagements beyond its own shores. The revised 2022 National Security Strategy enables Japan to launch counterattacks against military targets in enemy territory. This is a clear departure from past practices and signifies a substantial change in how Japan’s forces can respond to threats.

Scenarios

This far-reaching change in strategy comes at a time when relations between the U.S. and Japan are at an all-time high. Shortly after the Japanese government announced the sweeping overhaul of its defense and security policy, the two sides agreed to an enhancement of the presence and the quality of U.S. defense forces stationed on Japanese territory. The U.S. is clearly helping Japan strengthen its capacity for counterstrikes against enemies. The message to Beijing is clear: An invasion of Taiwan would lead to an escalation of unforeseeable dimensions.

Ultimately, the success of the new Japanese strategy depends largely on the leadership of the Liberal Democratic Party convincing the Japanese public that the nation needs to abandon its self-imposed restraints. This recognition faces two hurdles. One obstacle is from wishful thinkers who want the U.S. out of the country and for Japan to remain pacifist. Another comes from those among Japan’s economic leaders whose companies have high stakes in China and in the bilateral Sino-Japanese trade relationship.

While for the time being, the American-Japanese entente cordiale is riding high, there are strong forces within Japan’s society and economy that favor good relations with Beijing and express concern that a toughening of Japan’s military stance might not enhance national security but instead endanger peace in a volatile region. But for as long as Beijing continues its aggressive security policy, these voices will be diminishing.