Kazakhstan: A seamless succession?

President Nazarbayev has ruled Kazakhstan in a patriarchal fashion since 1990 and is one of the ablest politicians in the post-Soviet era. As the moment has come to hand over his office, he has prepared with his typical caution and astuteness. The odds are that the leadership transition will be successful, although a lot could go wrong.

In a nutshell

- President Nursultan Nazarbayev has anchored Kazakhstan's internal stability and international security

- His decision to step down in March 2019 has initiated a long-prepared leadership succession

- Mr. Nazarbayev's chosen successor, Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, may end up being a transitional figure

The political elite of Kazakhstan, the largest country in Central Asia, was not replaced or even seriously disturbed when the Soviet Union collapsed. No one who questioned the communist past even came close to assuming a position of power after 1991. Instead, the country is the last post-Soviet state to maintain an unbroken personal continuity in its political leadership since the USSR’s demise. Only now is this continuity facing a decisive test.

Because Kazakhstan never threw out its ruling elite, the ruling class that has remained in place since the late 1980s has undergone a gradual but deep evolution. The central figure in the power system is Nursultan Nazarbayev, an unusually talented, experienced and effective politician who served as Kazakhstan’s president from 1990 until his resignation in March 2019. Perhaps not coincidentally, he is perhaps the only national leader in the post-Soviet space who never lost touch with the everyday problems of ordinary people.

Leadership style

The unusual circumstances in which Mr. Nazarbayev came to power in 1989 as first secretary of the communist party in Kazakhstan is part of his mystique. In December 1986, Kazakhs in Almaty rose in bloody rebellion against the imposition of an outsider as leader of the local communist party – and the subsequent state of emergency that lasted for three years. It only ended when Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev elevated Mr. Nazarbayev to the position in 1989, restoring the important symbolism of Kazakh leadership to the republic.

President Nazarbayev survived in power as the USSR fell apart, even though (at President Gorbachev’s urging) he stayed away from the December 1991 Belovezha meeting that agreed to dissolve the Soviet Union. He appeared to adapt effortlessly to the new conditions of national sovereignty, displaying his trademark style of extreme caution in both domestic and foreign policy – especially when it came to relations with his northern neighbor.

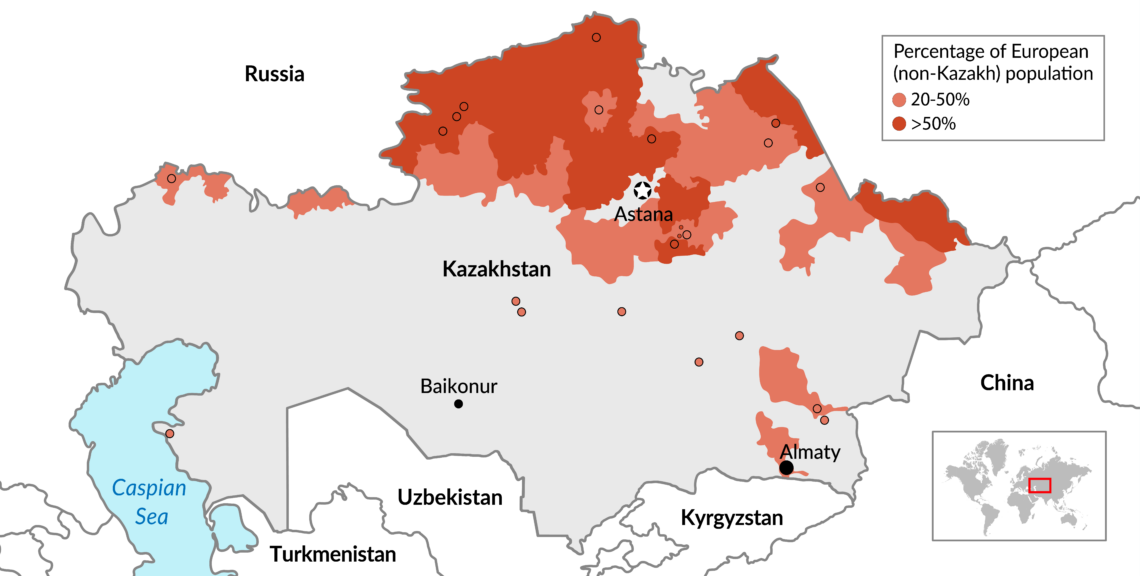

From the start, the “Russian question” was the central issue in Kazakhstan’s internal and external politics, by virtue of a long land border, devoid of natural barriers, and a large population of ethnic Russians concentrated in the northern part of the country and the cities. During the first decade of Kazakhstan’s membership in the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), President Nazarbayev’s guiding policy was a slow, patient drive to strengthen the Kazakh language and national culture.

The great operation of moving the capital from Almaty to Astana ensured Mr. Nazarbayev a place in history.

Mr. Nazarbayev’s most important undertaking, which ensured him a lasting place in Kazakhstan’s history, was the great logistical operation of moving the Kazakh capital from Almaty in the south to the new, planned city of Astana in the central part of the country. The reasons for the move were various, including a desire to escape the earthquake-prone environs of the former capital. However, the most important motivation was unspoken – a plan to use the administrative move to shift more of the Kazakh population north, into what had been ethnically Russian territory.

The political system that has evolved in Kazakhstan is a peculiar mix that combines elements of traditional social structures that survived the period of totalitarian rule with Russian and Western models. The linchpin holding the system together was Mr. Nazarbayev in the presidency. This setup has usually been described as authoritarian, but comparing Kazakhstan’s internal arrangements with those of its neighbors in the region, they could perhaps be better described as a modern version of the patrimonial state based on a strong leader with a broad base of social legitimacy and support.

National assets

A Poland-sized chunk of Kazakhstan is located geographically in Europe. The government has capitalized on this fact to justify its ambitions for closer ties with the European Union, and at times relations between Astana and Brussels have been close indeed.

A fixed element of Kazakh foreign policy has been the search for fields of cooperation with the EU. For example, in 2007, the German presidency prioritized the drafting of a special EU strategy toward Central Asia, with special emphasis on Kazakhstan. At that time, the EU-Kazakhstan Cooperation Council discussed not only bilateral relations but internal reforms in Kazakhstan. In the 1990s, this opening to the West was accompanied by strong political links with the United States.

As Central Asia’s most important state and something of a regional leader, Kazakhstan plays a key role in world affairs. One of its most pressing problems is growing pressure from China, all the more acute because of Kazakhstan’s relatively low population of 18.3 million, yielding a population density of only 7 per square kilometer. But Russia continues to be the country’s most important neighbor, and one with which the authorities in Astana are careful to maintain good relations.

Facts & figures

Kazakhstan: ethnic divide

Given Kazakhstan’s relatively weak geopolitical position vis-a-vis Russia, it is worth noting the relatively equal partnership between the two countries – much of which can be attributed to the personal stature of Mr. Nazarbayev, whom the Kremlin has always treated with great respect. Since 1991, Kazakhstan has been careful to conduct a multi-vectored foreign policy. Its international position has been strengthened by its abundant natural resources, especially oil, as well as by its central location on the overland trade route between Asia and Europe.

It is easy to find a modernizing strain in Kazakh policy. The government has encouraged and funded foreign university studies for elite groups, and has also staffed its own institutions of higher learning with Western faculty.

A major strategic asset is the aerospace industry, centered on the Baikonur Cosmodrome in the country’s southern steppe. This space launch center, established in 1955, is still leased to Russia under a 1994 agreement with the state-owned company Roskosmos. It is the largest such complex in the world, encompassing an area of 6,717 square kilometers, including the city of Baikonur, 11 assembly plants, nine launch sites and two airfields. Only in 2011 did Russia start building its own spaceport, the Vostochny Cosmodrome in the Amur Oblast of the Russian Far East, to lessen its dependence on Baikonur. The first launch operations from Vostochny began in 2016.

Stability first

Mr. Nazarbayev quickly realized that the key to staying in power was to ensure domestic stability. This was also in the interest of practically all of Kazakhstan’s major foreign partners. Leveraging Kazakhstan’s other assets, the Kazakh president focused on building a sturdy state administration and providing security and stability – at least by Central Asian standards – to ordinary citizens.

Given his priority of maintaining domestic stability and the Kremlin’s tacit readiness to make political use of Russian minorities in the post-Soviet space, Mr. Nazarbayev made a point of steering clear of “color revolutions” in former republics of the USSR, especially in Georgia and Ukraine.

The key challenge is to keep the current elite in power while preventing Russia from influencing the process.

He supported the rebirth of Islam – in its least radical variant – as the traditional religion of the Kazakh people, while at the same time stressing the nation’s multiethnic and multicultural character. Especially during the pontificate of Pope John Paul II (1978-2005), Mr. Nazarbayev cultivated relations with the Holy See and made many friendly gestures toward the local Catholic community.

After a three-decade run, however, the problem of succession reared its head. Mr. Nazarbayev had prepared for this moment for years. Hence the frequent constitutional amendments, repeated reshufflings in the senior leadership, and keen observation of a series of potential successors. This evolutionary process has been referred to by some writers as Mr. Nazarbayev’s perestroika.

The key challenge of this political transition was to keep power in the hands of the current power elite while preventing Russia from influencing the process, yet at the same time winning its acceptance of the result. That is why Mr. Nazarbayev was careful to institutionalize the succession through administrative reforms and constitutional changes. However, the trickiest problem is always how to pick the correct moment to execute the handover of power. A number of factors weighed on Mr. Nazarbayev’s decision to resign in March 2019, of which the most important was perhaps his health.

Yeltsin model

Russia experts will be familiar with the succession model followed by President Boris Yeltsin in 1999-2000, as he resigned to make way for Vladimir Putin. Yeltsin also realized the need for a controlled handover of power and carefully prepared for one. At the same time, however, he was subjected to pressure from competing political and economic interest groups, which deepened his doubts about the right moment for succession.

According to the generally accepted version of events, the framework for succession had been set and accepted by Mr. Yeltsin, but his associates (including a key group of advisors known as “The Family”) kept trying to influence the decision through the president’s daughter, Tatyana.

In personalist hierarchies, the timing of succession is critical – not just for the individual leader, but even more for his immediate family and political entourage. An uncontrolled or overdue leadership change might constitute a direct threat to their wealth and personal safety.

For some observers, the situation of Kazakhstan’s ruling elite in 2019 recalls that in Russia two decades earlier, with a few significant differences. Firstly, Mr. Nazarbayev is fully cognizant of the power shift, which cannot necessarily be said about Yeltsin in his waning years. Secondly, the transition in Kazakhstan has been carried out over a much longer period. Thirdly, the succession process was designed with several safety mechanisms that can be triggered in case of emergency.

Dressed for success

Above all else, it should be stressed that Kazakhstan’s leadership transfer is not yet over. Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, the former prime minister and foreign minister who was tapped to serve out the rest of Mr. Nazarbayev’s presidential term, is still a transitional figure and cannot be sure of his long-term position. His decision (consulted with Mr. Nazarbayev) to call a snap presidential election on June 9 was clearly intended to clarify this situation, though uncertainty lingered until the country’s electoral commission registered Mr. Tokayev as a candidate at the beginning of May.

Even so, many of the powers formerly vested in the presidency remain in the hands of Mr. Nazarbayev, who has retained lifetime chairmanship of the Security Council of Kazakhstan, leadership of the ruling Nur Otan party and a seat on the country’s Constitutional Council. His daughter, Dariga, continues to supervise the transition from her position as chairwoman of the Senate. There are many indications that she will play a pivotal role in the power structure that will emerge after the succession. Another possible player could be Mr. Nazarbayev’s nephew, General Samat Abish, currently the first deputy chairman of the national Security Council.

It is difficult to assess just how strong and widespread opposition to the Nazarbayev clan runs in Kazakh society.

For now, the most likely outcome in Kazakhstan is that its managed succession will succeed, ushering in a slow process of systemic changes from above. The country’s ruling caste is committed to this reform model, which supposedly is in harmony with traditional Kazakh culture. It also suits external players, who want a stable Kazakhstan for economic and geostrategic reasons.

Risk factors

Potential risks associated with the transition should not be overlooked. Since Mr. Nazarbayev’s personal authority played an important role in stabilizing bilateral relations with Russia, its diminution or absence could present the Kremlin with an opportunity to meddle in Kazakh affairs.

Recent years have also shown the potential for domestic unrest and protest movements in Kazakhstan. These could assume a purely social or political character, depending on whether they receive outside support. There are also some among the country’s business elite who would eagerly take revenge on the Nazarbayev family for preventing them from accumulating vast fortunes and achieving oligarchic status.

It is difficult to assess just how strong and widespread opposition to the Nazarbayev clan runs in Kazakh society. To the extent that such hidden sentiment exists, it can be expected to show itself more fully as time passes. For this reason, the coming presidential elections and their aftermath will be an especially crucial phase in Kazakhstan’s development. The country’s political transition is far from complete and bears careful watching.