Kazakhstan: Russia’s staunchest ally wavers

Could the linchpin in Moscow’s plan to reassert its control over former Soviet states be in danger of slipping away? Russia fears it might as Kazakhstan has been making overtures to the U.S. and China and chipping away at cultural relations. Astana cannot afford to break away from Russia, but an overreaction of Russia could tip the balance.

In a nutshell

- Kazakhstan is “de-Russifying” its language and place names

- It has made key deals with Washington and Beijing

- This worries Moscow, which could overreact and even intervene militarily

- Aware of this and other risks, Astana is unlikely to further provoke Russia

Recent developments in Central Asia have fueled speculation that a fundamental geopolitical reorientation may be in the offing. The Kremlin has long been concerned about China’s growing economic influence. Now it can add increasingly independent policymaking by the government in Kazakhstan. Russian commentators express anger over Kazakhstan’s perceived “neutrality” regarding Russia and its moves toward “strategic cooperation” with the United States.

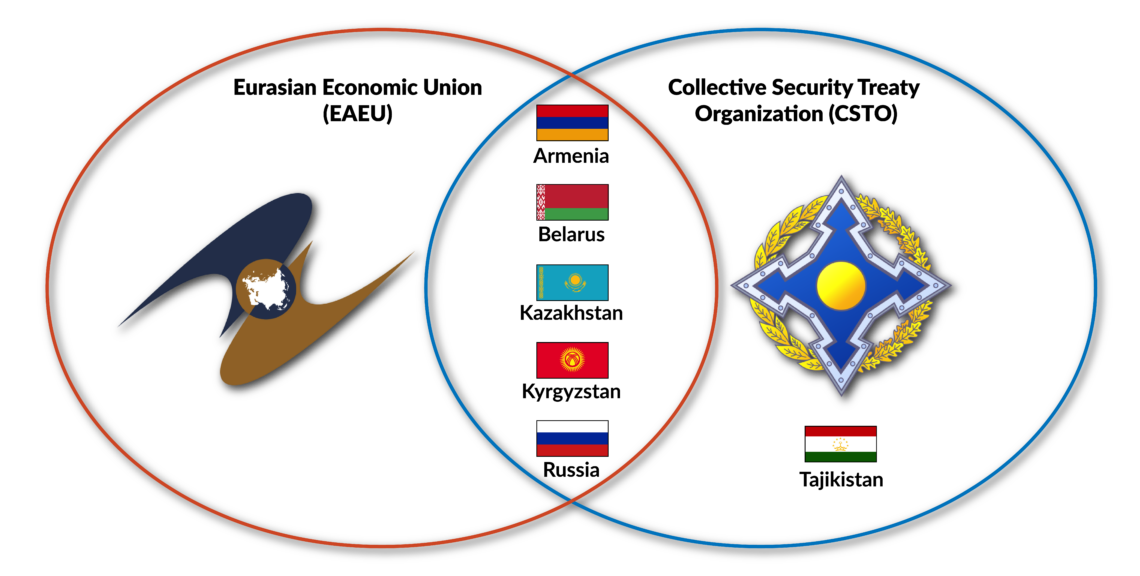

Kazakhstan has long served as the linchpin in Russian ambitions to reintegrate the post-Soviet space under its own control. It is a founding member of the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) and the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU). For the Kremlin, the thought of losing its staunchest ally must be deeply disturbing.

An important cause for concern lies in a perceived process of “de-Russification” in Kazakhstan. Russian-language place names are being replaced by indigenous ones. A decision has been made to abandon the Cyrillic script in favor of a Latinized alphabet. Leaders have vacillated on whether the Russian language is acceptable in government, and not a single person with a Russian background can be found in the ranks of cabinet ministers.

Commonality of the cultural space is regarded as a key element binding the former Soviet republics together.

The key is that “the commonality of the cultural space” was regarded as one of the three pillars (along with energy and defense) that bound the former Soviet republics together. As the Russian role as a provider of energy and defense has already been greatly eroded, it is logical that a challenge to the common cultural identity will be viewed as even more threatening.

Perceived insults

Russia’s aggression against Ukraine appears to be one of the main drivers behind these changes. Kazakhstan has not been alone in concern about who might be next in line for a visit by “green men” from Russia. Other key states, like Azerbaijan and Belarus, have found similar reason to develop a more cautious attitude.

Kazakhstan’s new security doctrine, adopted in September 2017, is so filled with Cold War jargon and so peppered with references to hybrid war and cyber threats that it can only be viewed as cautiously pointed at Russia.

The Kremlin has also viewed some aspects of recent Kazakh foreign policy as outright insults. For example, at the April 14 session of the United Nations Security Council, Kazakhstan abstained from backing a Russian-sponsored resolution to condemn U.S. and allied air strikes in Syria. The sense of fury that gripped Russian media was exemplified by television talk show host Vladimir Soloviev, one of the Kremlin’s prime attack dogs, who asked: “Should we expect the next Maidan [Ukraine-style revolt] will occur in and against Kazakhstan, so it can be torn away from Russia?”

Russian anger over “strategic cooperation” between Kazakhstan and the U.S. was fueled by a deal to designate the Caspian Sea ports of Aktau and Kuryk as additional points of transit for supplies to U.S. forces in Afghanistan. During his visit to Washington in January, Kazakhstani President Nursultan Nazarbayev received praise from U.S. President Donald Trump for agreeing to this. Russian media in contrast bristled with accusations of how the ports in question would be turned into “bases of the Pentagon and its allies.”

Facts & figures

Kazakhstan

In mid-March, Russia also reacted strongly against Kazakhstan’s decision to offer visa-free access to U.S. citizens. Although the ambition was to attract foreign visitors and investment, the Russian spin was that the move offers American spies a backdoor to enter Russia without detection. In a blatant display of postimperialism, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov demanded that in such matters, Astana must consult with Moscow.

‘Great game’ redux

The combined effect of these observations is to bring back memories of the geopolitical “great game” for influence over Central Asia that was played out in the 19th century between the Russian and the British Empires. This time around, the game features four different players, with very different assets and agendas.

Russia appears as policeman, providing security and demanding allegiance. China appears as banker, providing loans for infrastructure investment and demanding equity stakes in return. Turkey provides identity and promotes its agenda of pan-Turkism. The U.S. is mainly focused on transit rights for its Afghanistan operation logistics.

In this game, Kazakhstan is both the key player and the main playing field. While it has remained firmly linked to Russia in the field of security, it has been successful in attracting global energy majors to develop its energy assets. More recently, it has also emerged as one of the main transport corridors in China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

President Nazarbayev has successfully capitalized on these developments. Astana has been designated as the hub for negotiations on peace in Syria. Even more importantly, in mid-August, the port city Aktau hosted a summit on the Caspian Sea, at which the five littoral states finally managed to agree on a convention for the Caspian’s legal status. This will facilitate cooperation both in security and hydrocarbon exploitation.

Reasons for worry

President Nazarbayev recently turned 78. If a transition of power results in a serious succession crisis, it could throw the country into turmoil, in turn allowing for a challenge from radical Islamists. At the very least, Russia could be faced with a huge wave of refugees (interspersed with terrorists) flooding over its porous, 7,600-kilometer-long border.

If the Kremlin decided that another foreign military adventure is needed, Kazakhstan would be the logical choice.

What speaks against this scenario is that similar fears were not realized when long-serving strongman President Islam Karimov died in neighboring Uzbekistan in 2016. At the time, radical jihadists groups had a far more threatening presence in Uzbekistan than they have in Kazakhstan today. As it turned out, the clans that wield power in Uzbekistan were well-prepared to manage the transition. It is a reasonable bet that the same will prove true in Kazakhstan.

A considerably more disturbing scenario is a Russian Crimea-style land grab. If the Kremlin decided that another foreign military adventure is needed to avert attention from domestic trouble, Kazakhstan would be the logical choice. Russia’s pretext for such a move would be its self-arrogated right to protect Russian speakers abroad, no matter where they are.

Although many of the Russian speakers that lived in Soviet Kazakhstan have since moved “home” to Russia, ethnic Russians still make up about 20 percent of the population. Northern Kazakhstan remains predominantly Russian. It would not be hard for Moscow-backed agents to trigger nationalist anger over alleged discrimination.

What makes this scenario so disturbing is that the Kremlin has actively stoked these fires. In August 2014, President Vladimir Putin noted that Kazakhstan is a “state on a territory where no state had ever existed.” The remark was made as war was erupting in Ukraine, and it recalled his infamous 2008 quip to U.S. President George Bush: “You must realize, George, that Ukraine is not even a state.” Many other Kremlin-affiliated voices have since repeated the same sentiment. In January 2017, Duma member Pavel Shperov claimed that Kazakh territory was merely “on loan” from Russia.

Strong ties

In an extreme scenario, Kazakhstan might try to make a clean break with Russia. If Astana were to opt out of Moscow-controlled organizations like the CSTO or the EAEU, Russian intervention in some form would be bound to follow. Two reasons speak against this happening. One is that Kazakhstan remains linked to Russia in a multitude of ways, ranging from trade and security to education and personal networks. The other is that recent developments have given rise to fears about Kazakhstan becoming overly dependent on China.

Facts & figures

Eurasian Economic Union and Collective Security Treaty Organization

The Chinese authorities have expanded their persecution of the Muslim Uighur population in Xinjiang to also target ethnic Kazakhs living there. Increasing numbers of the latter have been brought to Kazakhstan and it has become increasingly difficult for Astana to turn a blind eye to Beijing’s actions.

In 2016, Kazakh authorities had to withdraw a proposal for agricultural land to be offered on long-term lease to foreign companies. Huge protests had erupted against the proposal, as many ordinary Kazakhs worried Beijing would use the opportunity to enhance its influence. Fear of being overpowered by China will keep Astana from making provocative moves against Russia.

While the likelihood of any of these negative scenarios coming about is minimal, the risk of serious confrontation will raise the stakes in the games that really matter: those concerning trade flows through Central Asia.

Trade flows

Kazakhstan finds itself at the crossroads between conflicting Russian and Chinese trade interests. While Moscow remains focused on retaining the old Soviet structures of south to north, built mainly to pump oil and gas, Beijing is investing heavily in the BRI, which envisions greater east-west trade. Having already made big strides toward reducing its dependence on Russian infrastructure, Kazakhstan now hopes to make billions of dollars from its cooperation with China.

The entry point for the BRI into Kazakhstan is at Khorgos, where the Khorgos Gateway dry port has been designed to serve as a “Rotterdam of the future.” At the other end of the country, on the shores of the Caspian, the port of Aktau has been modernized. In August, on the eve of the Caspian summit, President Nazarbayev inaugurated a new transport hub at the nearby port of Kuryk.

Russia is now mainly concerned with keeping U.S. military influence out of the Caspian region.

Beijing’s vision is that freight trains will travel 11,500 km from Lianyungang on the Yellow Sea to Duisburg, Germany in 13-15 days, compared to more than a month at sea. It is far from obvious that the investment will pay off. As most trains from China return empty, the sea route remains the more cost-effective option.

Yet, the geopolitical implications of reorienting the trade flows are already evident. Turkmenistan is also building a new port on the Caspian, while plans to build a Trans-Caspian pipeline may still be realized, despite hard Russian resistance.

Having had to come to terms with a loss of its prior monopoly on energy flows out of Central Asia, Russia is now mainly concerned with keeping U.S. military influence out of the Caspian region. This explains its strongly negative reaction to the Kazakh decision to offer the ports of Aktau and Kuryk as additional points of entry for U.S. logistics operations.

It is also significant that Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu recently announced that his country will move the base for its Caspian Flotilla from Astrakhan to a new deepwater port to be built at Kaspiysk, in Russia’s Dagestan region. Located on the opposite shore from Aktau and Kuryk, it is close to the center of the Caspian, allowing Russia the possibility to intervene against unwanted pipelines.

Turkey’s role

The most interesting feature going forward concerns Turkey’s role as an identity provider. Although Kazakhstan will remain locked into dependence on Russia, both for security and as a counterweight to China, the tectonic plates of linguistic and religious affiliations are shifting. The introduction of a Latinized alphabet will not only drive a wedge between Kazakhs and Russian speakers. By providing support for pan-Turkism against Russian pan-Slavism, the move will facilitate Kazakh relations with Azerbaijan and make more room for Turkey to operate across Central Asia.

The Kremlin’s inability to see the significance of these developments is both striking and symptomatic. Kazakhs will note that President Putin said Kazakhstan lay on “territory where no state had ever existed” just as they were preparing to celebrate 550 years of statehood. In this sense, Russia is its own worst enemy, and its arrogance is bound to feed a relentless erosion of both status and influence.