Turkey’s energy foreign policy at a crossroads

Energy cooperation between Turkey and Russia has ramped up recently. If it grows any closer, it could threaten EU interests, especially the key Southern Gas Corridor project. But its interests are also at risk if its dependence on Russian gas supplies grows.

In a nutshell

- Turkey sees the EU Southern Gas Corridor project as a priority

- Moscow wants to undermine the initiative with its own pipelines through Turkey

- The dilemma pits Turkey’s energy security and foreign policy objectives against each other

Until recently, Turkey has tended to prioritize its energy interests over foreign policy objectives. This no longer appears to be the case, as President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s domestic agenda increasingly overshadows other priorities. The change threatens Turkey’s long-term interests, both in terms of energy security and foreign policy.

Cooperation between Turkey and Russia on energy has increased in recent years. If this partnership grows closer, it could undermine the European Union’s Southern Gas Corridor project. Such a development would also threaten Turkey’s own energy security, and jeopardize economic and geopolitical interests that it has in common with Azerbaijan. Moreover, Southeastern European countries could seek to reduce their dependency on Turkey for gas imports, decreasing their overall demand for gas, expanding their liquefied natural gas (LNG) import capacities and buying more from offshore gas fields in countries such as Romania, Bulgaria, Israel, Cyprus and Egypt.

Confronted with the Turkish lira losing more than 40 percent of its value in the first two weeks of August, President Erdogan has not backed down in an escalating diplomatic conflict with the Trump administration in the United States. Mr. Erdogan has even threatened to cut old ties by moving toward “new markets, new cooperation and new alliances.” After the attempted coup in July 2016, he and his “Eurasianist” bureaucracy have favored a closer relationship with Russia and China and weakened Turkey’s traditional security ties with the West.

Pipeline politics

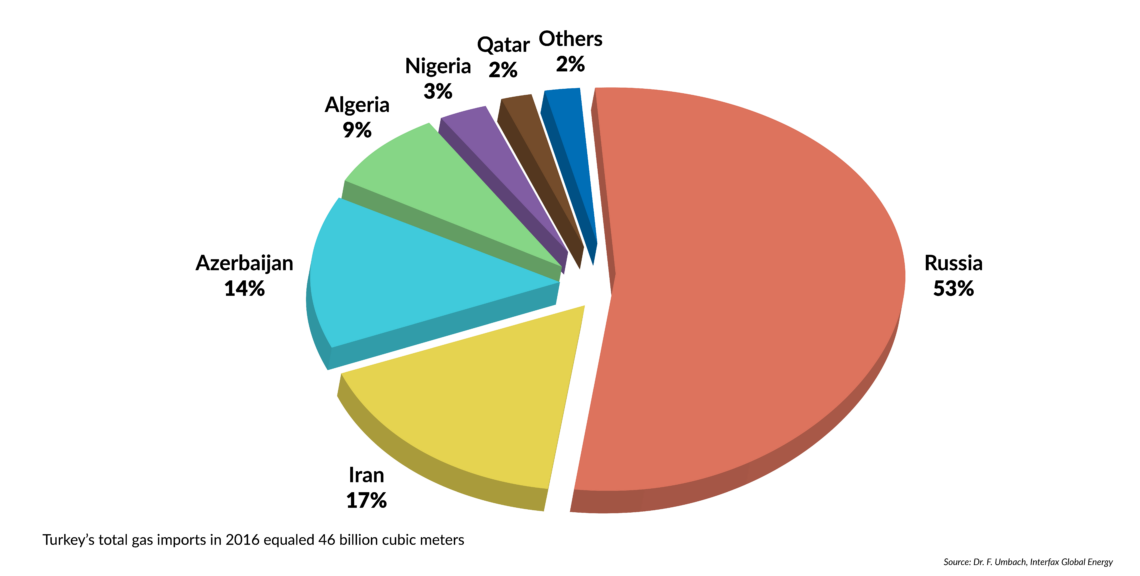

Ankara has given the go-ahead for Russia’s Gazprom to build a second TurkStream pipeline, with another 15.75 billion cubic meters per year (bcm/y) of capacity. With this new line, Russia will have yet another avenue (after the Nord Stream pipelines) for circumventing Ukraine in delivering gas to Europe. It will also be able to reduce flows through the Trans-Balkan Pipeline (TBP) as it supplies gas to Turkey and Southeastern Europe. Russia is not only Turkey’s most important gas supplier (accounting for 24.5 bcm or 53 percent of the country’s gas imports in 2016), but has also become its second-largest trade partner.

Turkey has become increasingly important as a hub for gas deliveries to Europe.

Against this backdrop of shifting policy, Turkey has become increasingly important as a hub and transit country for gas deliveries from Azerbaijan and other exporters to Europe. Questions have already arisen about whether Turkey will strengthen Europe’s energy security or weaken it in a growing alliance with Russia.

Positive signs for the EU

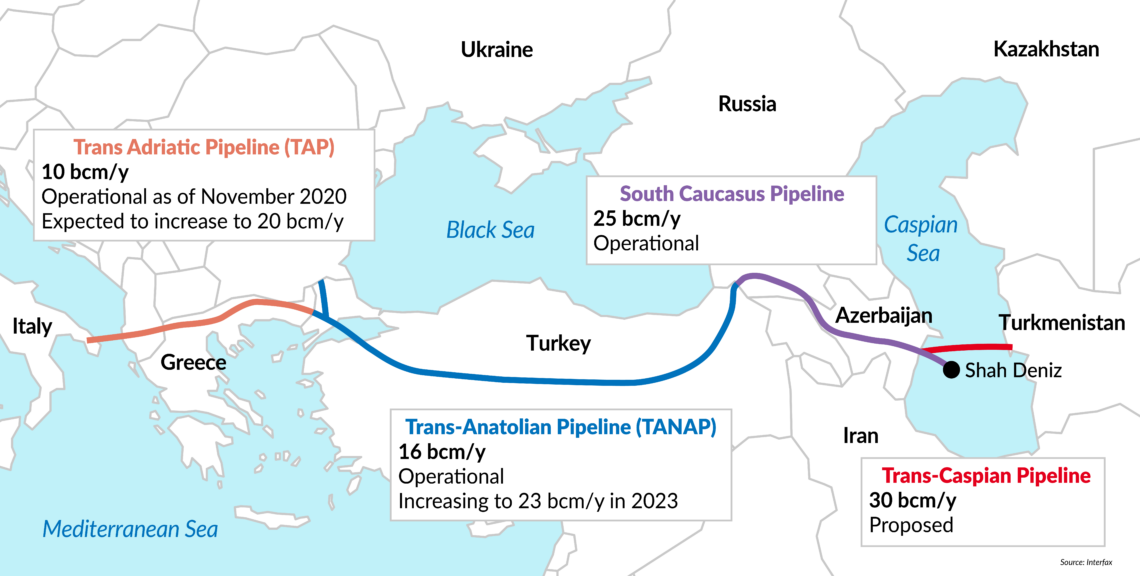

Despite the growing friction between the European Union and Turkey, President Erdogan and his government still consider the Southern Gas Corridor pipeline network as the country’s most important gas diversification project. The network includes the Trans-Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline (TANAP), the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline (TAP; to be completed by 2020) and the South Caucasus Pipeline (SCP); the gas will be supplied by Azerbaijan. Turkey – a centuries-old rival of Russia – does not want to become too dependent on Moscow. Azerbaijan, on the other hand, is Turkey’s only natural gas supplier that has not become mired in a serious price dispute or geopolitical conflict with Ankara over the last two decades.

As Turkey’s energy ties with Russia have grown, President Erdogan has sought to diversify his country’s energy mix and decrease its gas consumption, which more than tripled from 15 bcm in 2000 to 53.8 bcm in 2017. Turkey’s gas demand grew by nearly 16 percent last year, but this was only a temporary blip, as a wave of new coal-fired plants is coming online. In May, gas imports were already 19 percent lower than during the same period in 2017 due to the switch to coal, which is both cheap and plentiful in Turkey. Turkey’s “Vision 2023” policy, introduced in 2017, envisages boosting the share of (increasingly cost-competitive) renewables in the country’s energy mix to 30 percent, of coal to 30 percent and of nuclear to 10 percent, while reducing the share of gas to 30 percent by 2023.

Facts & figures

Elements of the Southern Gas Corridor

Turkey expanded LNG import capacity by building two large import terminals (with capacities of 8.2 bcm/y and 5 bcm/y). Ankara also signed contracts for another three floating storage and regasification units (FSRUs), which will give it more flexibility to manage seasonal peak demand and strengthen its negotiating leverage with Russia. Turkey will also soon launch a 24-hour gas trading market. At the end of July, it began sharing gas market data as part of its market liberalization process.

As a signatory to the 1991 Energy Charter Treaty, Turkey seeks to encourage investment and trade, as well as ensure reliable transit. It has been a dependable reexporter of natural gas to Greece since 2007, despite the countries’ often contentious relationship, covering almost one- third of Greek consumption. It is unlikely to be successful in using its growing transit status as a political instrument against the EU, since the TANAP-TAP pipeline network will only provide the bloc with 10 bcm/y – equivalent to just 2 percent of EU gas demand. Even if it expands deliveries to 30-60 bcm/y, TANAP-TAP will pale in comparison to Russian pipeline supplies to Europe (including Turkey), which amounted to more than 190 bcm in 2017.

Facts & figures

The Southern Gas Corridor project

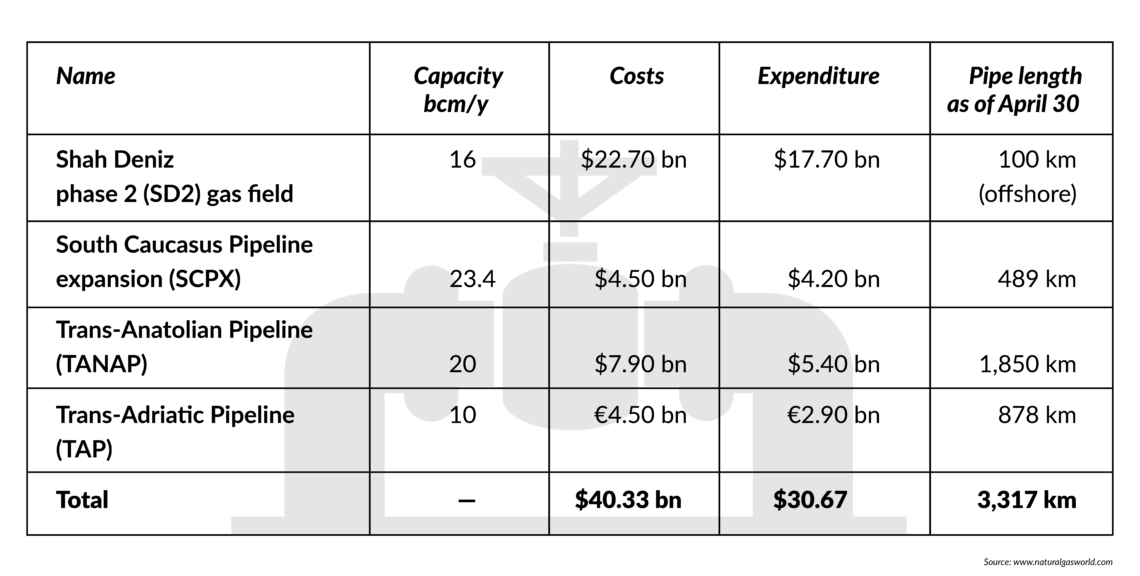

Turkey and Azerbaijan want to increase TANAP-TAP’s current 16 bcm/y capacity. At the end of June, about 95 percent of TANAP and 76 percent of TAP were completed. TANAP was already operational by the end of May.

The Southern Gas Corridor project, which delivers gas from Azerbaijan’s Shah Deniz phase 2 (SD-2) field, has received an exemption from newly-imposed U.S. sanctions on Iran, even though Naftiran Intertrade, a subsidiary of Iran’s state-owned oil producer NIOC, has a 10 percent stake in the field. On June 30, SD-2 began delivering commercial gas supplies via the completed South Caucasus Pipeline extension (SCPX) to Turkey. By 2025, the extension will increase SD-2 gas deliveries to Turkey from the current 25 bcm/y to 31 bcm/y. Via TANAP, that gas can be distributed in Southeastern Europe not just through planned bilateral gas interconnectors, but also via the Trans-Balkan Pipeline, with its 16.7 bcm/y capacity for reverse flows.

The State Oil Company of the Azerbaijan Republic (SOCAR) wants to increase its market share in Turkey’s gas sector to 20 percent of Turkish consumption. Achieving this goal will bind together the countries’ strategic interests even more closely. Azerbaijan can balance its economic ties with Russia by maintaining closer relations with the West. This could help keep Turkey from drifting too close to Russia’s geopolitical orbit and maintain its engagement in the Southern Gas Corridor project.

Facts & figures

Azerbaijan's gas projects, under development or planned

Those interests might be strengthened by the surprising August 12, 2018 agreement on the legal status of the Caspian Sea, resolving a nearly 30-year disagreement between its five littoral states. The long-discussed 300-kilometer undersea Trans-Caspian pipeline could finally be built. It would allow Turkmenistan, with the world’s fourth-largest conventional gas reserves of around 20 trillion cubic meters (tcm), to export 30 bcm of gas to Azerbaijan and then further to Europe via the Southern Gas Corridor. If that happens, Turkey’s growing status as a transit country and gas hub will remain dependent on cooperation with the EU.

Signs of a growing Turkish-Russian energy alliance

However, it cannot be excluded that Turkey will establish closer foreign, security and energy policies with Russia and China. Russia’s state-owned nuclear company, Rosatom, formally launched construction on the Akkuyu Nuclear Power Plant. The project will cost $20 billion and when completed, the plant will have four 1,200 megawatt reactors. The first unit is scheduled to start operation in 2023, with the other three units following by 2025.

Despite interest from nuclear power companies in China (State Nuclear Power Technology Corporation) and Japan (Mitsubishi Heavy Industries), it now looks doubtful that any other nuclear reactors will be built in Turkey. Such plants would decrease Turkey’s gas consumption (and therefore imports), but the country’s currency troubles and the decline of solar and wind power costs make nuclear a less viable option for Ankara.

Russia’s pipeline plans are clearly directed against EU-supported proposals.

To bring gas from its second TurkStream pipeline to Europe, Russia is considering a new connecting pipeline from Turkey to Baumgarten, Austria, which had originally been planned as part of its now-abandoned South Stream pipeline. The proposed line has been dubbed “South Stream Lite” and is supported by Bulgaria and Serbia. Gazprom could also simply exploit unused capacity in TAP – between 10 and 20 bcm/y – or revive the construction of the Interconnector Turkey-Greece-Italy (ITGI, also known as “Poseidon”) project. These Russian plans are clearly directed against EU-supported proposals such as the Bulgaria-Romania-Hungary-Austria (BRUA) and Eastring pipelines, which would allow Southeastern Europe to better diversify gas supplies away from Russian sources.

Facts & figures

Linking TurkStream to the European network

Turkey has had growing difficulty in reducing its dependence on Russian gas imports. Importing gas from Iraqi Kurdistan, for example, seems out of the question, at least in the short term. Ankara has become increasingly jittery about Kurds’ aspirations for their own state after the Kurdish Regional Government in Iraq held an independence referendum last autumn. Kurds form a large minority in Turkey, and Ankara considers the militant Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) a terrorist organization.

Second, even if gas from Kurdistan could be exported to Turkey, it might be sold by a Russian state-owned company. Rosneft is currently considering various options for an Iraqi-Kurdistan gas pipeline that would transport gas to Europe via Turkey.

Third, any gas imports from Israel to Turkey depend not only on better relations between the two countries, but also on a comprehensive settlement on Cyprus. The island is divided between a Greek-allied government in the south and a Turkish-allied government in the north, and a pipeline between Israel and Turkey would cross through its exclusive economic zone (EEZ).

It is unrealistic to expect Turkey to compromise on the Cyprus issue.

With President Erdogan’s allies in parliament, the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), adhering to an anti-Western foreign policy agenda, it is unrealistic to expect Turkey to compromise on the Cyprus issue. Last February, the Turkish navy blocked an Italian drilling ship from exploring in the Cyprus EEZ. Ankara believes the waters it wanted to explore fall under the jurisdiction of the Turkish-allied government in northern Cyprus, and wanted to prevent the internationally recognized government in Nicosia from claiming the natural resources there.

Fourth, Russia has used its leverage in Cyprus and Israel to block the construction of a Turkish-Israeli pipeline, as well as the planned EastMed gas pipeline from Israel to Cyprus and then further to Italy. Such pipelines would allow the EU and Southeastern Europe to diversify their gas imports, reducing Russia’s market share and weakening its geopolitical influence.

Fifth, the new agreement on the Caspian Sea only delineates territorial waters, sets rules for military cooperation and regulates water surface activities. The seabed’s natural resources, with estimated reserves of 50 billion barrels of oil and 9 trillion cubic meters of gas, have not been divided up, nor have any rules for undersea pipelines been agreed upon. These contentious issues will have to be worked out in bilateral agreements.

Finally, gas prices are currently low, making it difficult to turn a profit on selling Turkmen gas to Europe, since it must be transported some 3,500 km. Russia’s heavily subsidized pipeline gas could simply outcompete such supplies.

Scenarios

Any closer cooperation between Turkey and Russia in the realms of energy and foreign policy – and directed against the EU – will further complicate Turkish policy toward Azerbaijan and Southeastern Europe. If Ankara were to exploit the EU’s growing dependence on Turkey for gas imports, it might only produce some short-term gains for Turkey. Therefore, Turkey may try to balance its growing partnership with Russia by cooperating on the Southern Gas Corridor project, expanding supplies into the TANAP-TAP network with non-Russian gas and maintaining functional but ambivalent cooperation with the EU on energy and foreign policy.