Latvia and the Russia factor

The large Russian-speaking population in Latvia has long led to political and social difficulties, as Russia uses it to exert influence on the Baltic state. Recently, however, things have begun looking up. Riga’s politics may be turning a corner.

In a nutshell

- Moscow’s meddling has led to corruption scandals in Latvia

- Some fear Russia could use military intervention

- Riga has cracked down on illicit finance

Moody’s Investors Service recently affirmed its rating for Latvia at A3 with a stable outlook. This is the rating agency’s sixth-highest investment grade, and it is good news for the Latvian government. Grounds for optimism include a moderate debt burden, fiscal sustainability and an expected gross domestic product growth of 3.1 percent for 2021. Most importantly, Latvia won praise for cracking down hard on illicit finance.

In recent years, immense money-laundering scandals have racked Latvia’s banking sector. The verdict from Moody’s confirms that the country is making headway in tackling the issue. Latvian regulators have made significant progress in reducing financial sector risks, and prosecutors have been successful in bringing some of the worst transgressors to justice.

In its 2020 country-specific recommendations, the European Commission also identifies “effective supervision and the enforcement of the anti-money laundering framework” as an area where Latvia has made “substantial progress.”

Kremlin cronies exploit this factor in numerous ways, not just by corrupting financial markets.

While this is all good news, it also highlights the country’s deep vulnerability to infiltration by nefarious Russian interests that cultivate contacts among Latvia’s Russian-speaking population. Kremlin cronies exploit this factor in numerous ways, not just by corrupting financial markets. They work through Russian oligarchs, who are increasing their control over key Latvian infrastructure. Parties that draw their support from Russian speakers heavily influence domestic politics. And fears remain that an uprising of ethnic Russians could provoke an invasion.

Soviet legacy

The presence of numerous Russian-speaking residents, many of whom are not Latvian citizens, is a legacy from the days of the Soviet occupation. Moscow’s postwar drive to militarize and industrialize the Baltics came with a major influx of Russians. When Latvia regained independence, it had to decide how to deal with its Russian-speaking inhabitants, many of whom by that time had been born within Latvia’s borders.

In the early days of independence, Latvians faced the very real prospect of becoming a minority in their own country. As animosities intensified, the European Union demanded that the Russian speakers be integrated and granted citizenship. The question of language laws became a deeply divisive issue.

Russian ‘compatriots’

Although the controversies over alleged discrimination against Russian speakers have receded, the Russia factor remains significant, permeating Latvia’s politics, society and economics. Above all, it fuels fears of a Russian military intervention.

Such fears took on a new sense of urgency following Russia’s seizure of Crimea. Because of their exposed location, many considered Estonia and Latvia especially vulnerable. Scenarios for Russian aggression focused on the Kremlin fomenting unrest among Russian-speaking minorities and then claiming a right to intervene to protect them.

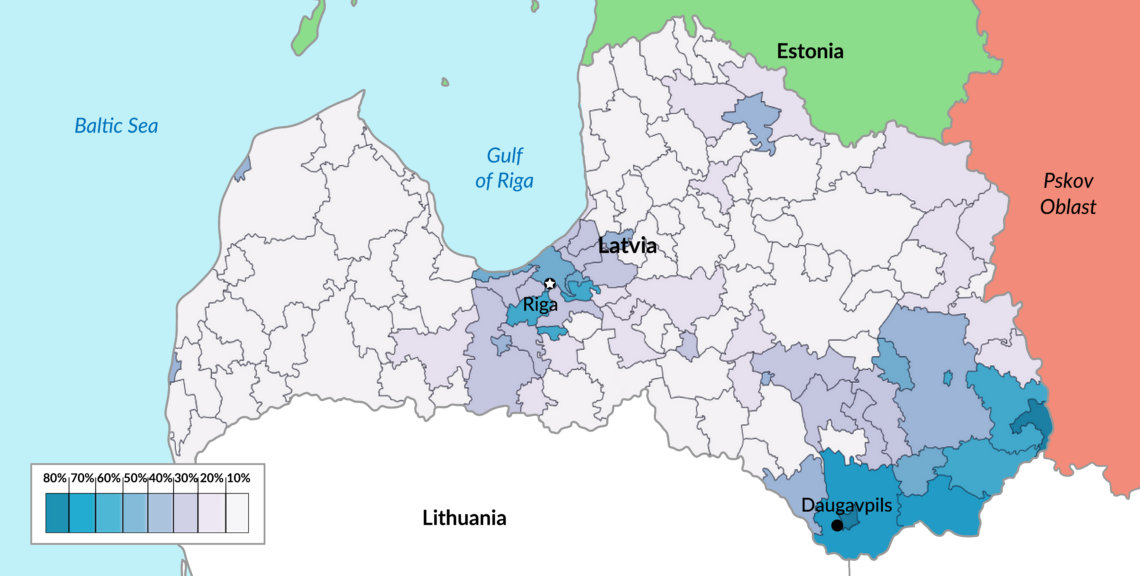

The cities of Narva in Estonia and Daugavpils in Latvia offer instructive examples. Both are located near the border with Russia, and both are heavily populated by Russian speakers. Street and shop signs are in Russian, and locals find it hard to understand why they should bother learning Estonian or Latvian. Daugavpils has even become known as “Little Russia.”

Facts & figures

Since the Kremlin’s propaganda has focused so heavily on the plight of Russians abroad, it has been easy enough to conjure up scenarios where threats become a grim reality. In a 2016 report, the Rand Corporation presented the results of a series of war-gaming exercises whose “unambiguous” conclusion was that Russian forces could quickly overwhelm the defense of NATO members Estonia and Latvia and reach the outskirts of the respective capital cities Tallinn and Riga in 60 hours or less.

These worries are overblown for two reasons. One is that it is hard to see what Russia could gain that would outweigh the cost of provoking an armed conflict with NATO. Even if Moscow were to secure deniability by repeating the stunt with the “little green men” in Crimea, the Western powers would be sure to inflict crushing retribution.

The other and more important reason is that war-gaming exercises have failed to present a credible scenario on how escalation into military conflict would begin. It is easy to suggest that local Russian speakers constitute a Trojan horse, and much can be made of the Kremlin’s rhetoric about patriots loyal to Mother Russia. The problem with such scenarios is that Russian speakers living in Latvia (and Estonia) are well aware that life on their side of the border is considerably better than on the other side. The neighboring Pskov Oblast is one of the poorest in Russia. Given recent developments in Russia under President Vladimir Putin, Russian speakers in the Baltics are unlikely to be persuaded by talk about being reunited with the homeland.

Even more important is that many of the Russian speakers have developed hybrid identities that combine a sense of being Russian with a parallel sense of being Latvian or Estonian. These identities have emerged in part thanks to special passports for “stateless” Russian speakers. These documents allow visa-free travel both to Russia and within the European Union. With Latvian or Estonian citizenship, it would become difficult to visit Russia.

All this suggests that while Russian speakers in Latvia and Estonia may have formed parallel societies in cultural terms, they are not particularly susceptible to Kremlin-backed agitation – at least not enough to open the door for an armed intervention. What remains of the Russia factor is linked to domestic developments. Here, vulnerabilities in the financial sector figure prominently.

Money laundering

News of what came to be known as the “Russian Laundromat” was first broken by an international network of journalists in 2014. Their investigation showed that between 2011 and 2014, a total of $20.8 billion had been moved from 19 Russian banks – via financial institutions in Latvia and Moldova – to more than 5,000 companies’ bank accounts across nearly 100 countries. Close to $13 billion was funneled into Trasta Komercbanka in Latvia, from where it could be moved on as “clean” European money. The onward journey of this flow of dirty Russian funds would involve numerous reputable international banks.

Latvia is on the road toward restoring its banking industry’s reputation.

The first steps toward a cleanup were prompted by pressure from the United States. Trasta Komercbanka was liquidated in 2016, and in 2018 the U.S. Treasury imposed sanctions that caused the collapse of other large Latvian banks. Meanwhile, senior officials were replaced, including the central bank governor, the bank regulator, and the head of the money-laundering watchdog. Latvia froze large sums of suspicious money, expelled dubious shell companies and opened several criminal investigations into shady dealings.

The good marks the Latvian government has received shows that it is on the road toward restoring its banking industry’s reputation, and thus the trust that is essential for the financial markets to work. Similar progress has been made in rolling back well-connected oligarchs’ influence over key infrastructure, like pipelines and port facilities.

A case in point is Aivars Lembergs. One of the richest people in Latvia, he served as mayor of the port city of Ventspils from 1988 until being suspended in 2008. A Latvian national, he also repeatedly stood as a candidate for prime minister from the Union of Greens and Farmers political alliance. In February this year, a court in Riga convicted him of bribery and money laundering. He was sentenced to five years in prison, a decision he is appealing.

His allegedly corrupt activities go back to the 1990s, when Ventspils was an important location for trade in Russian oil and fertilizers. The matter had been under investigation since 2007, and again it was pressure from the U.S. Treasury that sealed Mr. Lembergs’ fate. In 2019, Washington imposed sanctions on the city’s port authority and found that the suspended mayor was “directly or indirectly” linked to bribery regarding public contracts.

While Latvian authorities have been making good progress in cleaning up the financial sector and in rolling back the influence of well-connected oligarchs, the Russia factor remains an important hallmark of the country’s political system. This is a feature that has important implications for future developments in Latvia.

Political power

Though some Russian speakers have returned to Russia since independence, their presence in Latvia and Estonia remains significant. Around a quarter of the two countries’ respective populations are ethnic Russians and around a third speak Russian as their first language. A substantial share of votes in national elections go to political parties that draw their main support from these groups.

The strong performance of Russian parties makes it hard to form stable governments.

This not only implies that ethnicity has become a more important factor than traditional issues of left versus right. More ominously, the parties in question – the Center Party in Estonia and the National Harmony Party in Latvia – also have formal ties with Russian government circles and with United Russia, the country’s dominant political party. The strong performance of these factions makes it hard to form stable governments.

In Latvia’s 2018 national elections, Harmony secured 19.9 percent of the vote, depriving the ruling coalition of its majority. Five parties had to cobble together a coalition to prevent it from entering government. Other parties refuse to deal with Harmony for several reasons, including the party’s support for a failed 2012 referendum to make Russian an official language, its refusal to support Latvia’s official condemnation of Russian aggression against Ukraine, and its voting against legislation that cleared the way for cracking down on money laundering.

Most importantly, in June 2021, the Latvian parliament voted to strip Harmony member of parliament Janis Adamsons of his immunity against prosecution, clearing the way for an investigation into alleged spying for Russia.

Outlook

On balance, Latvia’s outlook remains positive. The country has weathered the Covid crisis with moderate damage. Its economy is picking up and it is successfully tackling crime and corruption. The remaining cloud on the horizon regards how the political system will deal with the Russia factor. The outcome of snap municipal elections in Riga in August last year suggests a transformation may be underway.

The elections were called following a series of corruption scandals that culminated in police raiding the home of Harmony party leader Nils Usakovs. The predominance of Russian speakers in Riga had helped him become mayor of the capital city in 2009. In April 2019, he was suspended from office. Faced with the added problem of internal party struggles, Mr. Usakovs managed to get elected to the European Parliament and left for Brussels.

The subsequent elections in Riga returned a severe defeat for Harmony. Parties that ran on a platform of progressive ideology – rather than ethnicity – had a strong showing. The results imply that old political divisions may be on the way out, as a younger generation demands policy based on issues rather than cultural or linguistic background.