Filling the void in Libya

Daily life is in a downward spiral, militias run Tripoli like criminal cartels, and as rival governments in Tripolitania and Cyrenaica vie for control, the desert interior is up for grabs. UN mediation has failed to overcome these centrifugal forces, and hopes for U.S. involvement were dashed by the troop pullout from Syria.

In a nutshell

- Libya remains torn between rival governments, local militias and foreign powers

- The UN’s top-down reconciliation process is not working and needs a rethink

- Khalifa Haftar seems to be implementing a plan to reunite the country by force

- Perhaps only the U.S. can mediate effectively, but it seems determined to stay out

President Donald Trump’s decision to withdraw American troops from Syria reset the geopolitical chessboard in the Middle East. One of the places where its repercussions are being felt is Libya. This may at first seem surprising, since the United States has lacked a significant footprint in the country since evacuating its embassy from Tripoli in 2014. Washington has been wary of Libyan exposure since the September 2012 attack on a U.S. mission in Benghazi, which killed Ambassador Chris Stephens and three other Americans and ignited a political firestorm at home.

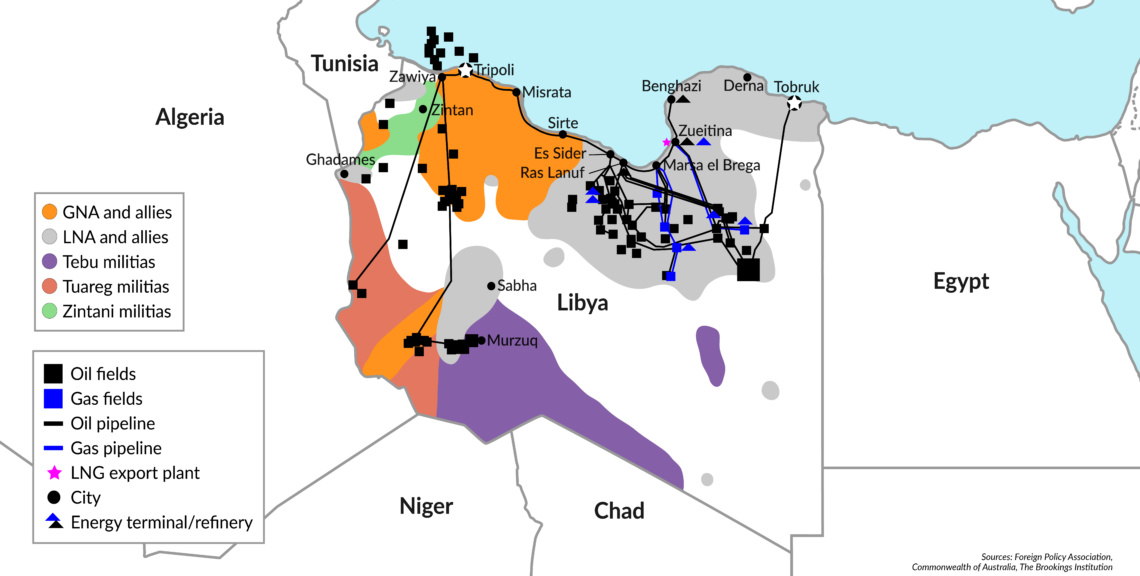

Yet after years of intense mediation by the United Nations, assisted by the European Union, France and Italy, the situation in Libya remains critical. The country is still divided between Tripolitania, nominally under the control of Prime Minister Fayez al-Sarraj’s Government of National Accord (GNA), and Cyrenaica, ruled by the country’s House of Representatives in Tobruk, backed by Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar’s Libyan National Army (LNA). Libya’s sparsely inhabited interior region, Fezzan, has been mostly left to its own devices – until recently, when Mr. Haftar’s forces seized some key outposts in the south, including the ancient city of Sabha.

Strategically, the Libyan desert capital has a great value, but the question is whether Mr. Haftar – whose roughly 25,000-strong LNA represents the strongest armed force in Libya – can muster the strength to push into Tripolitania and annihilate the hundreds of militias that exercise effective control over the area and the GNA. There are grave doubts on this score, even though Haftar forces are supported by Russia (whose private military contractors, including the Wagner Group, are active in Libya’s south) and receive funds and equipment from the United Arab Emirates and Egypt. France, for its part, launched air strikes on February 3 against unidentified Libya-based militias attempting to infiltrate into northern Chad.

Grim situation

The socioeconomic and political situation is equally grim. The country’s economy is struggling, despite the millions of barrels of oil being pumped from the ground every month. A package of economic reforms promised by the Sarraj government in September 2018 have not been implemented; the GNA itself is in disarray after a recent confrontation between the prime minister and his senior deputy, Ahmed Maiteeq; power blackouts and interruptions of water and fuel supplies are frequent; and despite gains against Islamic State, jihadist groups are still far from being eliminated – as witnessed by Derna, a Cyrenaican city that has been virtually destroyed by continuous fighting.

Thanks to their prime location and superior force, the Tripoli militias have emerged as real business cartels.

To this sad scenery, visible in almost every Libyan city (where almost 80 percent of the population lives), must be added the omnipresent militias. They are an inescapable presence in Tripolitania, where they enjoy virtually unchallenged control. The capital, Tripoli, has been chopped up by armed factions into neighborhood zones of control. Constant turf battles can escalate into heavy clashes, like the one in August 2018 between the GNA-affiliated militia “cartel” and the Tarhouna-based Kaniyat (7th Brigade) from south of the city. Scores of civilians were killed and road traffic into the capital was blocked for many weeks. A cease-fire brokered by UN Special Envoy Ghassan Salame did not last long. Fighting broke out again in February 2019 – apparently for control of the international airport – lasting a few days before the fragile truce was restored.

In this context, the quality of life for ordinary people – above all in western Libya – has entered a downward spiral. Public services are deteriorating, while abuse and violence by street toughs is a daily experience for many citizens. Thanks to their prime location and superior force, the Tripoli militias have emerged as real business cartels – able to “farm” state institutions like the Central Bank of Libya and the National Oil Corp. for income, while maintaining lucrative cash flows from smuggling narcotics, weapons and African migrants. The GNA – whose effective reach can be measured in city blocks from Tripoli harbor – is powerless to restrain these groups, which have become the country’s central problem.

Facts & figures

Haftar heads south

The situation on the ground has kept the UN Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL) from successfully organizing a National Reconciliation Conference, intended to bring Libya’s various factions together to lay the groundwork for elections and political reunification. As Mr. Salame remarked in a January 18 speech at the UN, reconciliation can only work “under the right conditions, with the right people [and] an outcome that is agreeable to the broad majority.”

Instead, the process has been disrupted by external powers (including Egypt, Russia, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Turkey, France and Italy, to name a few) pursuing their own interests. Separately and together, they have disrupted the natural selection of new, local political leaders. In the worst case, Mr. Salame warned, these “spoilers will sabotage the political advancement and undo any progress made” in Libya.

Trooping south

The alternative to a UN-mediated reconciliation process – or perhaps a preparatory maneuver to win advantage for its end stages – is for one of Libya’s feuding central authorities to gain the upper hand. With the GNA looking increasingly enfeebled despite official backing from Europe and the U.S., this is what Field Marshal Haftar and the Tobruk government appear to be trying to accomplish.

The key lies in gaining control of the south, a vast expanse of dunes and occasional oases that contains a good amount of Libya’s oil and gas. During their period of colonial rule, the Italians called this part of the country “the big sandbox.” Muammar Qaddafi’s regime (1969-2011) kept Fezzan under control by closely monitoring the tribes – above all their smuggling activities – while erecting a complex alliance system based on patronage and compulsion.

Mr. Haftar is a veteran of Libya’s border wars with Chad and has always appreciated Fezzan’s strategic importance.

After Qaddafi’s death, this elaborate structure collapsed and the south reverted to a no-man’s-land, patrolled by jihadi groups and smugglers. The GNA is too weak and too far away to exercise even nominal control. For this reason, Italian Interior Minister Marco Minniti decided in mid-2017 to negotiate directly with the southern tribes and individual Libyan cities to limit the flow of migrants. His successor, Matteo Salvini, chose an even simpler approach by closing Italian ports to vessels carrying migrants.

Mr. Haftar is a veteran of Libya’s border wars with Chad and has always appreciated Fezzan’s strategic importance. Two years ago, he began organizing LNA units to occupy territory in the south. Their initial deployments came under the guise of counterterrorism operations against al-Qaeda and Daesh. But there are many reasons why Fezzan played an important role in the field marshal’s calculations.

Securing the cooperation of its many tribes, while a torturous process, could provide the LNA with battle-tested new recruits. Control of the border with Chad would provide military benefits, especially by stopping flows of weapons and militants to the Tripoli militias, and potentially diplomatic ones as well, by establishing choke points for the migrant steams headed north. Most of all, seizing the remaining southern oil facilities – especially Sharara, the country’s largest oil field, near Murzuq – would give the LNA and the Tobruk government control of the bulk of Libya’s hydrocarbon resources. This could prove a decisive edge in any push to conquer Tripolitania and unite the country by force, or to be recognized as the leading authority in a peaceful unification process.

At the end of January, an alliance with the Awlad Suleiman tribe – traditionally opposed to the Tebu tribe that controls much of the southern border with Niger and Chad – allowed the LNA to take Sabha. Almost immediately, reports surfaced of violence directed against local Tebu. Shortly afterward, the LNA announced it had occupied the Sharara oil field, prompting the Tripoli government to dispatch forces southward in early February for a potential confrontation.

Absent feeling

The U.S. is perhaps the only international actor with the capacity and clout to get this situation in hand. For now, its presence is limited to a small contingent of special forces troops and surveillance drones for antiterrorist operations, but this is more a tactical than a strategic solution.

Before his resignation in December 2018 over the Syrian pullout, Defense Secretary James Mattis had shown signs of exploring a deeper political engagement in Libya, commissioning a report by the Brookings Institution on an alternative strategy to rebuild the country. The report (co-written by this author) was published in February, but with Mr. Mattis gone, its findings may no longer stir the interest of senior officials.

Meanwhile, the U.S. absence has left a vacuum that other actors have been quick to fill. One that bears careful watching is Russia, whose commercial interests in the country have been extensive since Qaddafi’s day, ranging from infrastructure and energy investments to very profitable military procurement contracts.

Libya’s proximity and position astride the main migration routes gives an extra source of leverage over Europe.

Strategically, Libya is important to Moscow for two reasons. First, its ports would make extremely good bases for Russia’s Mediterranean fleet. Second, Libya’s proximity to Europe and position astride the main migration routes gives an extra source of influence – and leverage – over Europe.

Diplomatically, wheels appear to be turning. On January 31, after consultations in Cairo, Russian Security Council Secretary Nikolai Patrushev met with his counterpart at the United Arab Emirates, Sheikh Tahnoon bin Zayed Al Nahyan, to talk about security cooperation and the situation in the Middle East and Africa. These meetings were followed by others in Saudi Arabia on security and counterterrorism. Mr. Patrushev has already met several times with Mr. Haftar to discuss possible joint strategies in Libya. In this context, the presence of the Wagner Group in Fezzan, alongside the LNA, is significant.

Scenarios

Libyan developments

If the LNA keeps advancing into Tripolitania, it will soon encounter the Misrata militias (which dominate the coastal strip east of Tripoli). If it comes to a fight, the militia cartels in Tripoli will also join in to defend their positions. This kind of confrontation could be a huge obstacle to future elections and unification.

Even more important, international mediation has provided no clarity about Mr. Haftar’s future role. The field marshal has always declared disinterest in politics; in reality, he is potentially the biggest domestic “spoiler” of the entire democratization process. In Benghazi, he is popular as a strongman who stands for order and against any form of religious extremism. One can be sure he would be happy to govern without elections, imposing his Cyrenaican model of governance on Tripolitania and Fezzan.

American options

At least theoretically, the Trump administration could listen to the suggestions from the Brookings task force on Libya and similar findings from the UN-supported Libyan National Conference Process. This would involve: 1) trying to stem the interference of some foreign powers; while 2) buttressing local forms of self-government in Libya while fostering a bottom-up democratization process. The other choice would be to stick to the limited antiterrorist operations the U.S. has been conducting for years, employing small detachments of special forces.

The second choice is clearly the most likely, if only because it is the least burdensome in economic and military terms. However, it is totally devoid of any long-term strategic vision for a trouble spot that could inflict extensive harm on Europe, and by extension, to the U.S. itself.

Third-party opportunities

Competitors eager to fill the void in the Maghreb include China and Russia. Both are interested in energy and infrastructure deals, as shown by Rosneft’s cooperation agreement with Libya’s NOC a few years back. The growing local presence of China and Russia will force an accommodation by Europe’s medium-sized powers, leaving U.S. interests increasingly isolated. In Russia’s case, at stake is potential naval access to Libya’s strategic ports.

This scenario casts Europe as the weak link. That accords with recent experience, which has shown Italy and France – the two Western countries most interested in Libya for economic and security reasons – consistently failing to pursue a common strategic line. At times, they have worked at cross-purposes, and occasionally (especially in the case of Italy), they simply look confused. There appears to be little understanding that under this approach, everyone must lose.