Low interest rates: How long will savers be penalized?

Low interest rates around the world are depriving savers of potential earnings. Just a couple of years ago, it seemed as if the normalization of interest rates was on the horizon. Now, economic and political realities portend a “low-for-long” scenario.

In a nutshell

- For a decade, monetary policy has punished savers

- Low interest rates help support irresponsible fiscal policy

- Central bankers see them as a way to easily reduce high debt

- This vicious cycle will likely continue; rates could go even lower

The past decade has been frustrating for ordinary savers. Ultra-low and even slightly negative interest rates are depriving them of decent returns on their nest eggs.

For previous generations, putting money in a savings account was a way to build one’s wealth. Today, doing so erodes it. Other forms of savings may offer superior yields, but often come with higher degrees of uncertainty. Yet what savers want most in these insecure times are safe assets. Chronically scarce, these do not necessarily generate much earnings. On the contrary, they can be costly to hold.

How long can savers expect this unfavorable macro-financial situation to last?

Point of no return

A couple of years ago, it seemed as if economic recovery, coming hand in hand with monetary policy normalization, was a credible scenario. Years of quantitative easing, notably at the European Union level, pushed short-term interest rates to record lows.

This tactic seemed to bear fruit in 2017, when the eurozone’s growth rates reached a 10-year high of 2.4 percent. Savers could realistically hope for a reversal of the disastrous financial cycle that had started abruptly in 2008 with the worldwide forced deleveraging of the excess debt accumulated in the decade before the crisis. Prominent economists such as Charles Goodhart expected long-term interest rates in advanced economies to return to their historical equilibrium values of 2.5 to 3.0 percent as early as 2025.

The most likely scenario is of lasting low interest rates coinciding with low growth.

Today, the optimistic “back-to-normal” scenario, based on a cyclical vision of the economy, looks unconvincing. The growth momentum did not last long, and the EU’s latest economic outlook does not look bright. Institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the European Central Bank (ECB) have had to revise their macroeconomic forecasts downward. A “low-for-long” scenario of lasting zero or mildly negative interest rates, coinciding with low economic growth rates in Europe, is now clearly the most likely.

Doomed to mediocrity

The IMF’s outgoing managing director Christine Lagarde once described this state of affairs as a “new mediocre” that henceforth would be the “new normal.” Other economists prefer to speak of “secular stagnation.” They claim that, beyond cyclical (crisis-related) factors, interest rates keep declining for structural reasons. Since the mid-1980s, sluggish productivity growth, inefficient labor markets, lack of investment and innovation and, above all, aging populations in advanced economies have been building up the conditions for a global “low-growth trap.” The 2008 debacle just made it all worse.

For years, the ECB has been surfing on the secular stagnation wave to defend itself against the accusation that its ultra-loose monetary policy is imposing a tax on savers. In 2015, it commissioned an official study to demonstrate that its policies were not “expropriating savers.”

Angst effect

Subsequent ECB reports imply that savers themselves are at fault for low long-term rates and mediocre economic growth. Europeans simply save too much. In times of crises, people are prone to what ECB Executive Board Member Yves Mersch calls the “Ricardian angst effect”: persistently low interest rates increase, rather than reduce, their propensity to save.

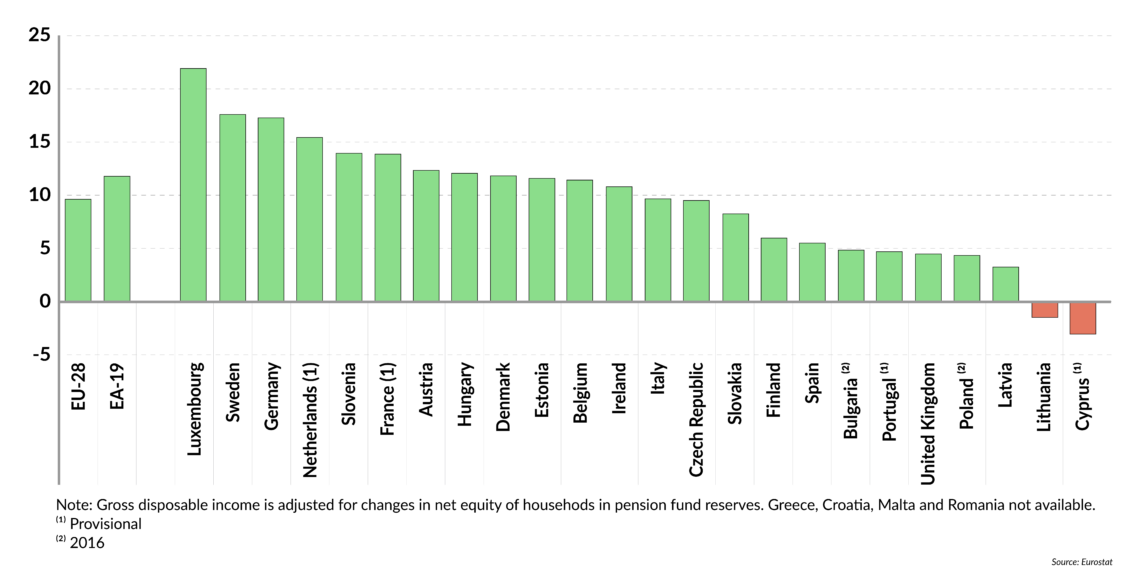

One reason for this might be that in times of great uncertainty, savers mostly seek to build up a reserve against future contingencies, not enjoy interest. Recent Eurostat data on the postcrisis evolution of gross household saving rates appear to confirm this trend above all for Germany, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Sweden.

Facts & figures

Gross household saving rate, 2017

(%, ratio of gross saving to gross disposable income)

Be it households frenetically searching for scarce safe assets or nonfinancial corporations piling up cash on their balance sheets, economic agents are accused of precipitating what former Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke pejoratively called a “global savings glut” – the counterpart of a “global investment slump.” Savers’ precautionary behavior is bad for the economy, the argument goes. By hoarding money that could otherwise be profitably invested, they are accused of contributing to a fall in long-term interest rates worldwide.

Undoubtedly, economic and demographic factors play an important role in shaping rates in the long run. Yet, the way the ECB minimizes the monetary influences on interest rates is stunning. The Bank’s reasoning implies that its massive stimulus programs in recent years, injecting trillions of euros worth of liquidity into European economies, only affected short-term interest rates, which, it says, are “not decisive for the vast majority of savers.” It is not made clear why and how central bank-induced short-term interest rates should trigger investment instead.

Policy choice

Even if one refuses to believe in the determinism of the secular stagnation hypothesis, the low-for-long scenario still seems the most plausible. Rates are likely to remain at their record lows for the near future not because of some law of nature, but because of politics.

Zero-percent interest rates help policymakers when a debt trap is looming. No one wants an interest-rate increase (except, of course, savers), since it would mean higher interest on public and private debt. When it comes to the former, consequences for national budgets could be significant. State solvency and hence global financial stability could be at stake.

‘Financial repression’ will certainly remain one of the favored measures.

As many countries’ debt-to-GDP ratios remain a cause for worry, debt-reduction strategies will likely stay atop the EU’s list of priorities for years to come. And “financial repression” will certainly remain one of the favored measures.

‘Capturing’ savers

A few years back, economists contemptuously used that term – “financial repression” – to describe policies that allow central banks to liquidate government debt, either by capping interest rates or targeting higher inflation.

Increasingly presented as a smart instrument for implementing macroprudential regulation (i.e., limiting risk to the financial system as a whole), “financial repression” has found new favor in the aftermath of the crisis, notably with a group of IMF economists publishing a series of studies advising governments to “capture” (by underpaying) domestic savers through near-zero interest-rate policies. The strategy is presented as a convenient way to deal with the highest levels of public debt the world has ever known.

Confiscating revenue from savings to reimburse global debt could be an exceptional measure adapted to exceptional circumstances. However, policymakers struggling to manage chronically depressed economies are increasingly considering the use of slightly negative rates over longer periods as well.

In a severe economic downturn, central banks will have to break deeper into negative territory.

Several obstacles remain. Monetary policy might prove ineffective if interest rates are too close to zero. If a severe economic downturn occurs, central banks will be unable to make further cuts without breaking more seriously into negative territory.

Blasting through zero

As the eurozone heads for another recession, the ECB faces a dilemma. Either it lets policy rates fall significantly below the psychological barrier of zero (low enough to “absorb the excess of saving over investment”) and accepts the blame for expropriating savers, or it keeps refusing to do so (President Mario Draghi’s policy so far) and is blamed for the economy’s slow recovery.

Christine Lagarde was recently nominated to take over for President Draghi at the ECB in November, and it is not clear which path she will follow. Under her leadership of the IMF, which began in 2011, a young generation of economists – among them Ruchir Agarwal and Miles Kimball – have audaciously defended the use of “deep” negative policy rates. Could their policy recommendations inspire Ms. Lagarde in her new job? Or will she hold the line with Mr. Draghi’s “patient, persistent and prudent” strategy?

Deeply negative rates would be difficult to enforce in Europe. Savers would lose big. For example, if rates were fixed at minus 4.5 percent (the average rate cuts needed to rescue an economy from recession lie between 3 and 6 percentage points, according to an IMF study), a savings account with 1 million euros would shrink by 45,000 euros every year.

People would almost certainly withdraw their money immediately, triggering a bank run, with all that implies for financial stability. How could that be avoided?

Operating instructions

In a recent working paper, Mr. Agarwal and Mr. Kimball elaborate solutions for “enabling” deeply negative rates. The first, labeled the “clean approach,” would introduce an exchange rate between paper currency and electronic money (bank deposits). In other words, cash and noncash are treated as distinct currencies. The negative “paper currency interest rate” (PCIR) is presented as a new policy variable for deterring depositors from withdrawing cash. Complementary measures are discussed in this context, reaching from imposing quantity restrictions on cash to abolishing it altogether, as deep negative rates seem to work best in cashless societies.

So far, savers have grudgingly accepted the losses imposed on them.

If there were too many legal barriers, the authors propose (as a second-best option) a “rental-fee approach.” Here, central banks are invited to charge commercial banks a fee for the cumulative net cash withdrawn over a period of time. The latter would subsequently pass this cost on to their customers.

New morality

So far, savers have grudgingly accepted bearing the losses imposed on them by moderate financial repression. Will they still do so if negative rates were to fall below tolerable levels?

The IMF researchers insist that, if implemented, the saver-unfriendly policies they have been theorizing over the last few years must be supported by efficient communication tools for promoting a broad political and social “acceptance.” To mitigate saver rebellion, they propose “subsidizing” low-income households – in other words, a sort of welfare measure that consists in compensating poor families for the losses imposed on their (supposedly meager) savings.

How such redistributive programs would look – some form of “punitive tax” imposed on wealthy savers? – is not spelled out. Nonetheless, there is a barely concealed Keynesian (and even Piketty-style neo-Marxist) undertone in this type of argument. Low and middle-income households are expected to have a higher marginal propensity to spend (thereby fueling the economy) than well-earning households and corporations, which, on the contrary, are supposed to have a higher propensity to save (thereby harming the economy).

Saving is foremost an act of investment and essential for sustainable economic growth.

When it comes to creating the right incentives for what Mr. Mersch, the central banker, calls “behaving responsibly in a low-interest rate environment,” it is mostly the high-earners that are targeted – precisely those who are accused of exacerbating the global savings glut – the supposed source of evils such as income and wealth inequality.

What the European Systemic Risk Board fears most in a low-for-long context is that seasoned savers, in search of yields and alternative forms of finance, will be drawn into ever riskier waters, outside the heavily regulated (and therefore relatively safe) banking sector. The Board calls for “enhanced supervision of risks stemming from bank-like activities in the nonbanking sector,” implicitly assuming that people are too shortsighted to be trusted to invest their own money in reasonable ways.

What is, in fact, shortsighted is the deprecatory concept of saving shared by many policymakers and economists of our time. Rather than amounting to leakage from the economy, saving is foremost an act of investment and, therefore, essential for sustainable economic growth.

The current policy discourses tend to address the issues of saving and wealth in terms, at their worst, reminiscent of Keynes’ “hatred of thrift.” While some of Keynes’ legendary expressions, such as the “euthanasia of the rentier,” would shock today, the ideas behind them seem to attract plenty of contemporary economists and policymakers.