The false end of quantitative easing

The ECB made the fateful announcement that it would phase out its bond-buying program – called quantitative easing – by the end of this year. But, it is not the same thing as ending the ECB’s ultra-lax monetary policy. By rolling over its balance sheet of bonds, policymakers could keep oxygenating the euro area’s economy for years.

In a nutshell

- The ECB will end its net bond purchases by the end of this year

- However, euro-area growth remains hampered by corporate and government debt

- This suggests rates will stay near zero as the ECB rolls over its maturing bond portfolio

On June 14, the Governing Council of the European Central Bank (ECB) came together for a policy meeting in Riga to make a long-awaited announcement: it could now envisage putting an end to its ultra-accommodative monetary policy, known as “quantitative easing” (QE).

The decision did not really come as a surprise. For months, Europe’s top central bankers had been urging ECB President Mario Draghi to shut down the controversial QE program. Now, for the first time, the ECB communicated a possible date – the end of September 2018 – for phasing out its nonstandard monetary policy measures. Net asset purchases could end as soon as January 2019.

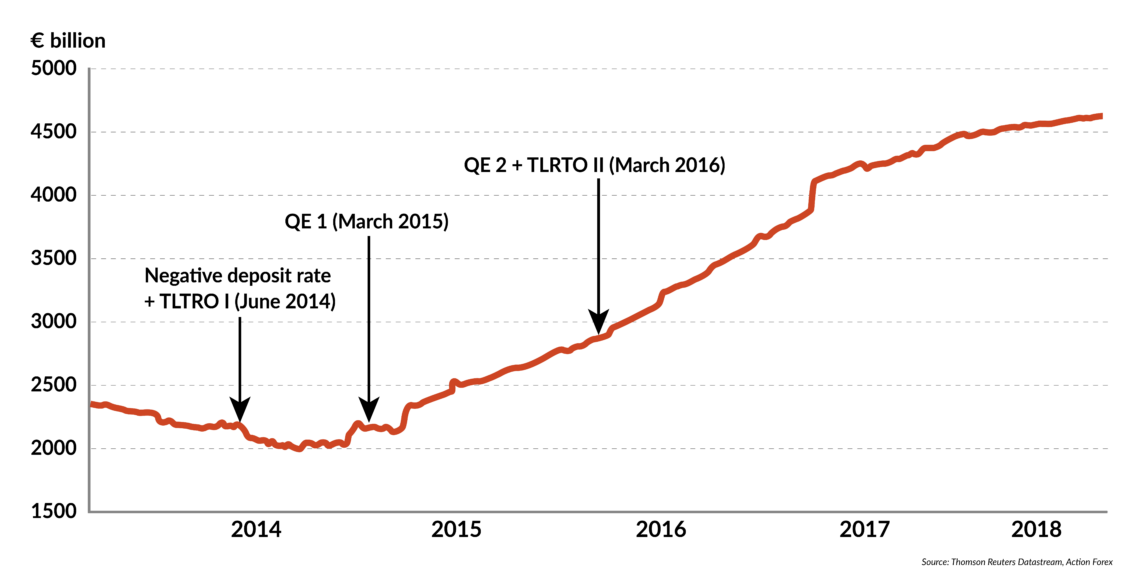

Initially conceived as a short-term emergency remedy for countering dangerous deflationary trends in the euro area, QE had soon become the ECB’s signature policy, based on a long-term commitment to buy bonds from commercial banks at the stupefying pace of 60 billion euros a month. Since May 2015, the ECB thus pumped over 2.5 trillion euros of liquidity into the eurozone economy through its expanded asset purchase program (APP), allowing distressed markets to breathe again.

Useful distraction

There is widespread agreement that the APP’s shutdown should occur gradually and be implemented with great caution. In fact, it had already begun in January 2018, when the stimulus package was halved to 30 billion euros each month. This should be further reduced to 15 billion euros by the end of September, before being phased out completely by the end of December.

Latvia’s central bank scandal provided the ECB with a handy pretext to deflect awkward policy questions.

As it happened, the two-day session of the ECB’s Governing Council in Riga was overshadowed by a corruption scandal involving the governor of Latvia’s central bank, Ilmars Rimsevics, who was barred from attending the meeting. The scandal reflected wider issues with Latvian commercial banks, several of which had recently come under pressure over dealings with dubious Russian clients. One of the country’s biggest lenders, ABLV Bank, was put in liquidation in February 2018 after the ECB determined that it “was failing or likely to fail” following allegations of money laundering and noncompliance with EU sanctions against North Korea.

This situation made for an uncomfortable and even embarrassing atmosphere at the Riga meeting. However, it had the beneficial side effect of providing the ECB with the perfect shield to deflect awkward questions about its rather opaque statement concerning the alleged end of its ultra-lax monetary policy.

Inflation boost

At his post-meeting press conference in Riga, Mr. Draghi chose his words with care:

We anticipate that, after September 2018, subject to incoming data confirming our medium-term inflation outlook, we will reduce the monthly pace of the net asset purchases to 15 billion euros until the end of December 2018 and then end net purchases.

Clearly, this “anticipation” leaves open the possibility for the bank to retreat from its position, in case incoming economic data, notably concerning inflation, do not live up to the ECB’s expectations. From the start, the Governing Council had made the duration of APP conditional “on the extent of progress towards a sustained adjustment in the path of inflation to levels below, but close to, 2 percent in the medium term.”

May 2018 was the first month in years to yield an inflation rate (1.9 percent) compatible with the ECB’s target. As recently as February, annual consumer price growth had been only 1.1 percent, rising to 1.3 percent in March and April. But by July, headline inflation had accelerated to 2.1 percent, backing Mr. Draghi’s case for announcing, at least provisionally, the end of QE.

Three months of data are not enough to speak of a durable trend toward sustainable higher inflation.

Of course, three months of data is not enough to speak of a durable trend toward sustainable inflation. As the ECB president himself admitted, the welcome price data in May and June were to a considerable degree caused by increases in food and energy prices. If these rather volatile items were excluded, inflation slowed from 1.1 percent in May to 1.0 percent in June, a figure as low as in the early postcrisis years.

Even so, in comments to the European Parliament in early July, Mr. Draghi saw no reason to rescind the decision to withdraw from QE. In his view, inflation “can be expected to pick up” on a sustained basis because the economy should continue to grow – mainly thanks to the ECB’s “very effective” monetary policy.

S(t)imulated growth

Last year, the eurozone economy enjoyed its strongest growth (2.8 percent) in a decade, and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Economic Outlook forecasts satisfactory, though lower, growth rates of around 2.0 percent for 2018 and 2019.

The recent improvement in EU growth can undoubtedly be ascribed to years of ultra-loose monetary policy, which has created the easiest lending conditions of all time. This seems a far cry, however, from the “smart, sustainable and inclusive growth” that the European Commission had aimed for in its Europe 2020 strategy. Various international observers, ranging from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to the OECD, have warned about the inevitable long-term decline of productivity in an aging Europe. All agree that not enough structural reforms have been implemented, even though last year’s short cyclical pickup would have provided an excellent opportunity to do so.

Instead, a decade of cheap credit has driven many companies and households into unendurable debt. Close-to-zero interest rates encouraged banks to lend to ever more vulnerable customers. In consequence, low-productivity firms (so-called “corporate zombies”) have proliferated in many European industries. Their lack of competitiveness, in the long run, could undermine the recent economic recovery. Recent data suggest that about one in every 10 European corporates can be categorized as a “zombie” – i.e. a company that would fail in a normal market, but is kept alive by financial doping.

Not surprisingly, the quality of European corporate debt has steadily deteriorated over the years. Commercial banks’ balance sheets have become overstretched with bad (or, worse, junk) loans, which is worrisome in itself. As The Economist puts it, we could soon be watching a “triple-B movie” as Europe follows the lead of the United States, where the largest group of corporate bonds is rated “just one notch above junk” by various international rating companies. Global corporate debt, associated with malinvestment and the misallocation of resources, provides a perfect cocktail for triggering the next worldwide crisis, as another article in The Economist claims. The trigger could be the effective withdrawal of monetary stimulus or so-called “quantitative tightening” (QT), which will soon be put in practice by the U.S. Federal Reserve.

Another issue is that low or zero interest rates have made banks too dependent on short-term funding. The liquidity oversupply created by the ECB’s aggressive QE policy, were it to continue, could destabilize financial markets and eventually set off crashes. Being able to buy and sell quickly is vital, of course, particularly during a crisis. But at some point, a healthy economy needs people to resume acting as responsible, long-term investors, not just traders hooked on short-term profits.

Sovereign trap

Government and corporate debt are creating vulnerabilities that will weaken long-term growth in the EU. The euro area is already affected by a contraction in domestic demand caused, among other things, by the aggressive tax policies of heavily indebted states.

Governments that have clung for years to fiscal stimulus policies are now desperate to dig themselves out from under a mountain of debt (or at least slow its explosive growth), even if it means putting economic expansion at risk. France is an example of a eurozone economy that has slowed more than expected in recent months due to particularly high tax pressures. This could send the euro area into a new slump even before the announced withdrawal of QE takes effect.

Rising interest rates might plunge Italy into a debt trap, with fateful consequences for the entire EU.

The greatest threat to future growth in the eurozone undoubtedly comes from Italy, the currency bloc’s third-largest economy. Italy’s debt clock is ticking toward a vertiginous 2.5 trillion euros, and its debt-to-GDP ratio has exceeded 130 percent for years.

The question is whether rising interest rates in Europe (to be expected in case monetary policy is “normalized”) might plunge Italy into a debt trap, with fateful consequences for the entire EU. By late May 2018, Italy’s borrowing costs had already risen significantly in reaction to the country’s latest anti-EU political turn. As a result, the quality of Italian debt has been downgraded, and Mr. Draghi’s home country could soon cease to be eligible for the ECB’s bond-buying program.

Theater of the absurd

Interestingly, while making the QE exit announcement, Mr. Draghi made the paradoxical claim that key interest rates will continue to remain at their record lows in Europe (currently 0.0 percent) for a long time – at least through the summer of 2019, and possibly beyond.

This formulation puts the pronouncement that QE is ending in a different light. The enigmatic words of the absurdist playwright Samuel Beckett – “the end is in the beginning and yet you go on” – find a strange echo in Mr. Draghi’s struggle to escape from a policy that is running on empty.

When the ECB president promises to walk out on QE, what he really means is that the bank will give it another go.

As Mr. Draghi explains:

We intend to maintain our policy of reinvesting the principal payments from maturing securities purchased under the APP for an extended period of time after the end of our net asset purchases, and in any case for as long as necessary to maintain favorable liquidity conditions and an ample degree of monetary accommodation.

In other words, what will stop in 2019 is the purchase of assets to enlarge the ECB’s monetary base. The bank will simply rely on its current, colossal balance sheet to oxygenate the European economy for a long time to come. Call it what you will, this is still QE, just in a disguised form.

In the medium term, Europe should not be short of easy money and interest rates are not likely to go up.

The new policy works as follows. As soon as a bond held under QE reaches maturity (on average, this happens after six or seven years), the redeemed principal is immediately reinvested in new asset purchases. This QE reinvestment has already started over the past year as older bonds have come to maturity. According to Positive Money Europe, assets worth 47 billion euros were repurchased in this way in 2017. The amount should triple to 147 billion euros this year and reach 180 billion euros in 2019. No estimates are available for subsequent years.

Real closure

The inescapable conclusion is that, at least in the medium term, Europe should not be short of easy money and interest rates are not likely to go up. The ECB is carrying 2.55 trillion euros of bonds on its books that, as they mature over the next few years, will be available to stimulate the eurozone economy all over again. In theory, this operation could be repeated indefinitely. A Fed-like shrinking of the ECB’s balance sheet seems out of the question, at least on Mr. Draghi’s watch.

The problem is that a prolonged stimulus, rather than supporting sustainable growth, risks overheating the European economies even more. This applies particularly to the wealthier countries, where asset price bubbles are inflating fast in the financial and property markets. Austria, Germany and Luxembourg are already seriously concerned. At the same time, QE reinvestment might accentuate the vulnerability of the less wealthy, highly indebted Southern European countries (Italy, Greece, Portugal and, to a lesser extent, Spain) to financial and real shocks. These economies have become addicted to cheap credit and are obviously incapable of getting along without it.

November 2019 could be a crucial moment for Europe The “man who saved the euro” will step down, and his successor will be appointed to lead the ECB. Once this new boss runs out of ammunition, he or she may eventually face the thankless task of bringing real closure to the era of cheap money. That would mean preparing Europeans for the next inevitable major economic recession – unless, like Mr. Draghi, another rhetorical device is found to postpone the demise of QE. Either way, at the end of the road a downward spiral awaits.