Belarus in the crosshairs

President Alexander Lukashenko is facing unprecedented turmoil both at home and on the foreign front with Russia. The Kremlin appears to be losing patience with the strongman’s trick of playing off Russia against the West and could decide to intervene.

In a nutshell

- Moscow wants Minsk to be more pliable in exchange for oil

- President Lukashenko is looking West to gain leverage

- If provoked, Russia could attempt to incorporate Lukashenko

On May 24, 2020, more than 1,000 demonstrators gathered for a rally in Minsk, the capital of Belarus. It was one of the largest manifestations of the year so far. The aim was to prevent long-serving President Alexander Lukashenko from winning a sixth term in office. The protestors will not succeed. On August 9, the incumbent will sweep to yet another resounding victory in the upcoming round of elections.

The security services have already intensified their crackdown on activists and journalists in what Human Rights Watch called a “new wave of arbitrary arrests.” The usual election rigging can be expected. It may be tempting to conclude that this is merely business as usual, in what Western governments have enjoyed branding as the “last dictatorship in Europe.” But this time around, there could be some surprises.

Oil barter

The playing field has been fundamentally transformed in recent years. First, there was the crisis in Ukraine, which saw relations between Russia and NATO hit rock bottom. Then came the coronavirus pandemic and the accompanying collapse in global energy demand, which created a perfect storm for Russia. There has never been so much uncertainty since Mr. Lukashenko first came to power in 1994.

Western governments have learned – the hard way – how far the Kremlin was ready to go to prevent Ukraine from moving closer to the West. Even if Belarus is not Crimea or Donbas, there are signs of a looming confrontation with Russia on the horizon.

Even if Belarus is not Crimea or Donbas, there are signs of a looming confrontation with Russia on the horizon.

Belarus and Ukraine are both wedged in between Russia and Europe. Neither has a tradition of statehood before the collapse of the USSR and both play a pivotal role in Russian energy policy as important transit routes for Russian pipelines to Europe. But there are also vital differences in their respective vulnerabilities.

One is that Belarus is formally joined with Russia in a commonwealth called the Union State, constraining its sovereignty. To date, both sides have found good reasons not to implement a treaty signed in 1999. Mr. Lukashenko values his freedom to – carefully – play off Russia and Western governments against each other. Meanwhile, many Russians are wary of the implications of allowing him into the tent.

Recurring rumors that the union may be about to be consummated have thus far proven ill-founded. But a recent spate of speculation indicates that the Kremlin may finally be getting ready to use force to do so and that it is looking to replace President Lukashenko.

Although Ukraine also has a long tradition of getting cheap energy in return for political malleability, to date, Belarus has been spared the kind of open confrontation that eventually led to war between Moscow and Kiev. As this is about to change, Minsk realizes that its vulnerability extends beyond gas prices and transit fees.

In addition to the Russian pipelines, Belarus is also home to essential refineries that process Russian crude into gasoline for export to Europe. The country has long been making good money on this business. But Russia has become frustrated, feeling that President Lukashenko is not showing due appreciation. At the end of 2019, when the annual contract expired, Russia halted its deliveries of crude.

The cessation was triggered by disagreements over a broader overhaul of Russian energy taxes and subsidies. Yet, there could be little doubt it was also a signal that Moscow is no longer willing to offer preferential terms without significant political and strategic gains. In mid-December, Russian President Vladimir Putin stated that, “given the unresolved issue of the union state’s buildup,” it would be a mistake to subsidize Belarus further.

The situation took a new dimension when United States Secretary of State Mike Pompeo visited Minsk.

The conflict came to a head in February, when the two leaders met in Sochi to discuss the integration process. The Belarusian head of state claimed that Moscow was pushing for a state merger that would entail unified energy prices. He also said he was “convinced that neither Russians nor Belarusians will ever want to follow this path” and insisted he would continue to pursue other options. With specific reference to the energy price negotiations, he said he would “not be kneeling” before Russia every time contracts are up for renewal.

Facing West

An important driving force in the present escalation of tensions is that Western governments are responding to increasing Russian weakness and frustration by seeking warmer relations with Belarus.

One possible scenario is that President Lukashenko will counter growing pressure from Russia through a continued rapprochement with the EU. Brussels has already toned down its criticism of human rights violations in Belarus. It could offer Minsk better conditions within its Eastern Partnership. Upping the ante, Europe could even offer enhanced energy cooperation, much like it tried – and failed – to do in Ukraine.

On past occasions, Belarus has successfully diversified its energy imports. It has bought crude from both Venezuela and Iran. Earlier this year, it imported about 80,000 tons of oil from Norway, to be followed by shipments from Azerbaijan and Saudi Arabia.

While such moves irritated Russia, the situation took a new dimension when United States Secretary of State Mike Pompeo visited Minsk in February 2020. It was the first visit to that country by a sitting head of U.S. diplomacy since 1994. Its purpose was to pave the way for deliveries of American crude oil. Shipments will be made to the port of Klaipeda in Lithuania, a NATO member, and onward via rail.

It was significant that this visit followed hints of a rapprochement with NATO. In a statement made at the end of 2019, the former Chief of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of Belarus, Major General Oleg Belokonev, suggested that “Belarus is ready for joint exercises with NATO. There are talks on possible formats.” What the general had in mind was probably an arrangement like that of Serbia – maintaining close ties to Russia but also military connections to NATO.

This would be an entirely new situation. To the Kremlin’s military strategists, the very thought of Belarus defecting to NATO must be the ultimate nightmare.

Facts & figures

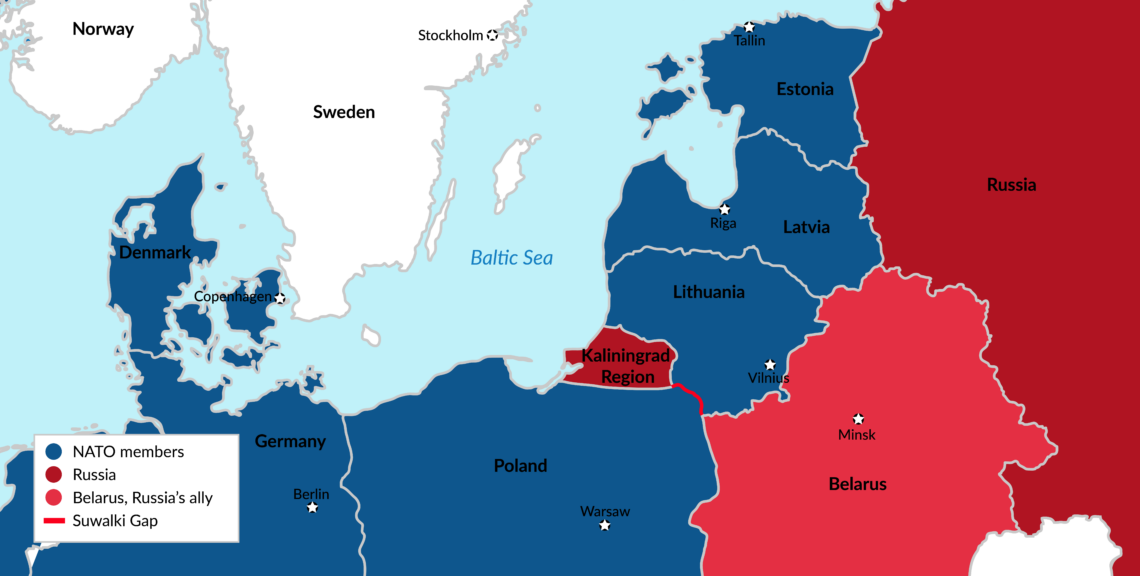

Russia’s position in the Baltic region hinges critically on the militarized Kaliningrad exclave. With a garrison of 15,000 troops, equipped with heavy artillery and advanced long-range ballistic and anti-aircraft missiles, it ensures that any NATO advance up the Baltic Sea would be met with costly consequences.

However, Kaliningrad is surrounded by Lithuania and Poland, neither of which is on friendly terms with Moscow. The land border between the two is about 110 kilometers wide. Stretching from Kaliningrad to Belarus, it is known as the Suwalki Gap, and it holds the key to the regional security balance. As long as this territory is in the hands of NATO, Kaliningrad will remain isolated.

Given that any Russian ambition to reduce this gap would have to go through Belarus, in the case of a military confrontation between Russia and NATO, Minsk would be a key player. But can President Lukashenko be trusted?

Belarus is a member of the Russia-led Collective Security Treaty Organization, but Moscow has not been allowed any permanent military bases in the country. At the time of the Zapad war games held in Belarus, Kaliningrad and Russia in September 2017, there was speculation that some of the Russian troops taking part would simply stay on in Belarus. That did not happen. On the contrary, last year, Belarus turned down an official Russian request to access an air force base. Moscow described the decision as “unfortunate.”

Scenarios

The current rise in tensions is nothing new. Seeking concessions from Russia by making overtures toward the West has long been Mr. Lukashenko’s favorite trick. But while Belarus has recently sought more pragmatic ties with the U.S., the EU and China, Russia remains its primary trade and energy partner. The danger at present is that Western governments, tempted by Russia’s weakness, could goad Mr. Lukashenko into overplaying his hand.

On May 15, Secretary Pompeo noted that the first shipment of U.S. crude for Belarus would depart that week. He claimed that the deal strengthens Belarusian sovereignty and “demonstrates that the U.S. is ready to deliver trade opportunities for American companies interested in entering the Belarusian market.” If the specter of broader American involvement in the economy of Belarus is linked to the threat of joint military exercises with NATO, the Kremlin could very well decide it has finally had enough.

Moscow could also attempt to incorporate Belarus by force. This would entail removing Mr. Lukashenko from power, which would not be hard, and putting into place a government that would accept joining the Russian Federation. Such a move would be rewarded by full control over vital energy infrastructure, further enhancing Russia’s grip over Europe’s energy flows. Russian troops would gain full access to military airfields and forward bases for ground troops.

This would have a significant impact on regional security. The permanent presence of Russian troops and hardware in Belarus would not only imply a heightened threat against Poland. It would also place Russian forces in pole position to reduce the Suwalki gap swiftly. Since the two highways that pass through the gap are the only land corridor through which NATO could come to the rescue of its Baltic member states in the event of a conflict with Russia, it would drastically enhance their exposure.

The most likely path ahead remains brinkmanship from President Lukashenko, rewarded by more periodic concessions from Russia. It was significant that, in early April, the two sides agreed to resume deliveries of Russian crude. But Western governments would be well advised to realize that the Belarusian strongman is presently skating on thinner ice than ever before. President Putin is under tremendous pressure at home. A sudden mood swing in his foreign policy could have far-reaching consequences.

It is sobering to note that the wars in Georgia and Ukraine followed a period of intense endeavors to bring both countries closer to the West. And it is especially chilling that the Russian aggression against Ukraine came as a complete surprise to those same Western countries.