Madagascar after the coup

In contrast to the earlier transfer of power, the current transition places Madagascar under direct military rule.

In a nutshell

- Madagascar’s coup reflects broader regional unrest

- The military will likely preserve broad geopolitical continuity

- Post-coup authorities are expected to focus on trade and investment

- For comprehensive insights, tune into our AI-powered podcast here

Madagascar has become the latest addition to the wave of military takeovers sweeping across Africa, joining other former French colonies such as Mali, Niger, Gabon and Burkina Faso. Ever since independence in 1960, the Malagasy Armed Forces have been a decisive force in national politics.

The recently ousted president, Andry Rajoelina, first came to power in 2009 during mass protests, becoming, at 34, the youngest head of state on the African continent. As in 2009, the 2025 coup and subsequent transfer of power were triggered when the elite military unit CAPSAT (the Personnel Administration and Technical and Administrative Services Corps of the army) aligned itself with the demonstrators. This time, however, the transitional authority will be headed directly by the military.

Although less pronounced than in other former French colonies, anti-French sentiment has also played a role in Madagascar’s recent political turmoil. Mr. Rajoelina stepped down as head of the transitional authority in 2014, only to return in 2018, when he won the presidential election. He was reelected in 2023, despite the opposition accusing him of electoral fraud. Controversy also surrounded his candidacy due to claims that he should have been disqualified after acquiring French citizenship in 2014.

However, the main catalyst for the anti-government protests was widespread economic discontent. Madagascar, a nation of about 30 million people, abundant in minerals and agricultural potential, has a predominantly young population, with a median age of around 19. According to 2024 World Bank data, approximately 80 percent of the population lives below the poverty line. Between 2012 and 2024, the country dropped 22 places in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, from 118 to 140.

Catalysts of unrest

The immediate trigger for the protests was a series of persistent power outages and water shortages in the capital, Antananarivo. Following a recognizable pattern, what began as spontaneous demonstrations over failures to provide basic services soon evolved into broader demands for political change. The protests were largely driven by members of Generation Z: a cohort of urban youth facing limited economic prospects and increasingly convinced that their concerns are ignored by those in power. Young activists now possess powerful tools for information-sharing and mobilization through social media, as illustrated in Madagascar by the online movement Gen Z Mada. From Nepal and Sri Lanka to Morocco and Angola, similar youth-led movements have emerged, often connected by digital culture and symbols like the straw-hat “Jolly Roger” flag from the anime One Piece, which represents a rebellious spirit against corrupt and oppressive systems.

Facts & figures

Timeline of the coup

September 25 – Protests ignite: Youth demonstrations over power and water outages spread as security forces crack down and curfews are imposed.

September 29 – Government dissolved: President Rajoelina dismisses the prime minister and Cabinet, but protests widen over hardship and corruption.

October 8 – Dialogue rejected: Protesters refuse the president’s invitation to talks and call for continued demonstrations.

October 11 – Army unit defects: An elite military unit joins protesters and Colonel Randrianirina urges Mr. Rajoelina to step down.

October 12 – Coup leadership emerges: Col. Randrianirina claims control of the armed forces while Mr. Rajoelina denounces an attempted power grab from hiding.

October 13 – President in exile: Mr. Rajoelina says he fled over an alleged assassination plot and insists he remains the legitimate leader.

October 14 – Military takes power: Parliament impeaches Mr. Rajoelina and Col. Randrianirina declares a military takeover with an 18-month transition.

October 15 – Colonel claims presidency: Col. Randrianirina announces he will assume the presidency and be sworn in at the high court.

In Madagascar, the protests quickly gained momentum, spreading to other cities and attracting growing participation from civil servants, unions and opposition parties. Ultimately, the decisive moment came when the elite military unit CAPSAT chose to side with the demonstrators, announcing that it had taken control of the armed forces, suspended the constitution and effectively removed President Rajoelina from power. Colonel Michael Randrianirina assumed the presidency after the military takeover.

Geopolitical implications of the Madagascar coup

Over the past decades, the Indian Ocean region, stretching from the Horn of Africa to Southeast Asia, has become a key arena of geopolitical and geoeconomic competition among major and middle powers. Situated off Africa’s southeastern coast, along the Mozambique Channel, Madagascar is the world’s fourth-largest island. Geography remains a central factor shaping the country’s foreign policy: For island nations like Madagascar, the dynamics of great-power rivalry, relative isolation and resource constraints are inescapable, regardless of the ideology or domestic policies of the ruling regime.

Facts & figures

At the same time, Madagascar’s strategic position and wealth of critical minerals have drawn the attention of global powers. Countries such as China, Russia, the United States and India all have interests in the island. While China is, by a far margin, the world’s top producer of graphite, Madagascar is among the world’s five largest producers. The country also produces cobalt and nickel, minerals essential for the production of electric vehicle batteries and energy storage technologies.

For China, Madagascar’s top trade partner, the island is especially significant within the Maritime Silk Road initiative. Madagascar was among the first African nations to sign a memorandum of understanding with China in 2017 on cooperation within the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Following a broader pattern, Chinese investments in Madagascar within the BRI framework have decreased. However, despite this retreat, Beijing’s interest in Small Island Developing States, including Madagascar, is expected to persist in the medium term as part of its geopolitical and geoeconomic ambitions.

Russia is now better positioned to increase its influence in Madagascar. According to the speaker of Madagascar’s National Assembly, Moscow has sent a shipment of weapons to the National Guard, under “lawful international cooperation.” Importantly, the Russian ambassador in the country was the first diplomat to meet President Randrianirina after he was sworn in, and the first trip of the newly appointed president was to Moscow.

The U.S. has also expressed interest in enhancing Madagascar’s maritime security capabilities, and bilateral cooperation has increased as great power competition dynamics accelerate in the Indian Ocean region. Madagascar is also relevant to the U.S. strategy to reduce dependence on China for critical minerals.

More by African affairs expert Teresa Nogueira Pinto

- How Italy is increasing its footprint in Africa

- Power, gold and guns shape Mali’s uncertain future

- Ivory Coast: From Paris to Petrobras

One example is the Toliara Mineral Sands megaproject, which was acquired by the U.S.-based company, Energy Fuels. The Toliara Project was suspended in 2019 and, in 2024, the suspension was lifted. While an initial agreement between the government and Energy Fuels has been reached on the $2 billion project, a final decision is still pending. India also has an eye on Madagascar. The island is part of its strategy to secure its maritime security interests through a network of allegiances along critical sea lanes in the Indian Ocean, intended to counter Beijing’s “String of Pearls.”

While recent events are unlikely to significantly alter Madagascar’s relations with Beijing, Moscow, Washington or New Delhi, they are expected to further diminish France’s geopolitical and economic influence in the country, echoing developments seen across several other former French colonies.

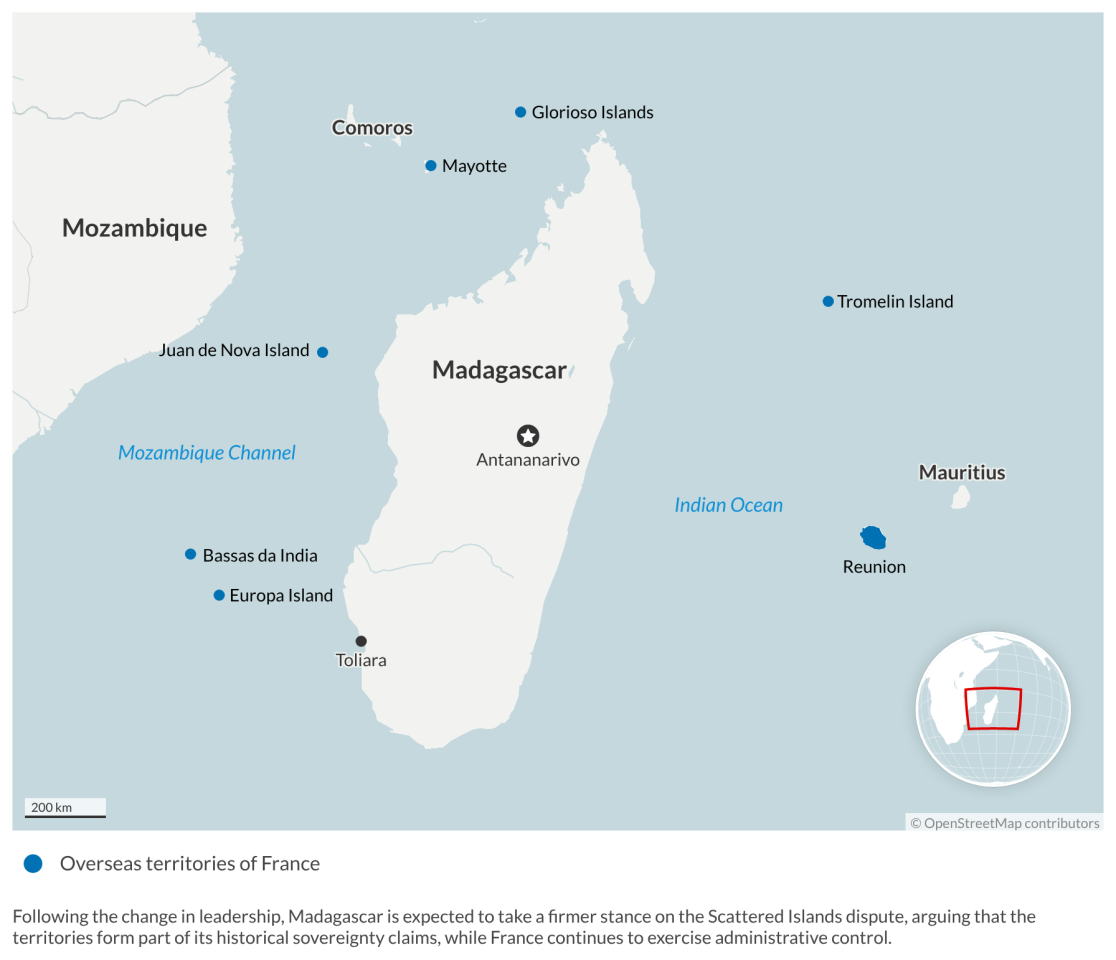

One of the new government’s first actions was to revoke the Malagasy citizenship of the former president, whom many protesters had accused of being overly aligned with French interests. Madagascar, following the recent leadership change, is also expected to become more vocal over the Scattered Islands dispute. While Madagascar claims historical rights of sovereignty over the uninhabited coral islands of Glorioso, Juan de Nova, Europa and Bassas da India (a claim presented to the United Nations and supported by China), France holds administrative control of these territories.

Scenarios

Most likely: Status quo in geopolitical alignment

From a political perspective, events in Madagascar replicate dynamics seen across Africa and Asia, as young and urban populations take to the streets in protests. These events may reinforce a contagion effect. However, from a geopolitical perspective, the most likely scenario is continuity.

The likelihood of continuity stems largely from CAPSAT’s long-standing involvement in Madagascar’s political landscape. To be sure, there is an important difference between events in 2009 and in 2025. While, in 2009, the transition process was led by a civilian, Mr. Rajoelina, who was then the mayor of Antananarivo, it will now be led by a military officer.

However, the transitional authorities are expected to accommodate mediation attempts and maintain the dialogue with political parties and civil society, who, at least for now, support the post-coup solution. The decision to appoint former businessman Herintsalama Rajaonarivelo as prime minister, while criticized by Gen Z protesters, also indicates ongoing engagement with international allies and investors.

Madagascar’s insularity increases the likelihood of geopolitical continuity. While Russia, which has long tried to increase its influence in the region, is attempting to fill some momentary vacuums, success in the long run remains doubtful. Unlike what happens in countries like Mali, for example, the post-coup regime in Madagascar is less dependent on external security providers and is expected to focus more on trade and investment opportunities.

That the post-transitional government enjoys, at least for the time being, widespread support, will likely encourage international investors and geopolitical partners to refrain from rupture.

Less likely: Madagascar becomes hostile to foreign investors

While less likely, a scenario of rupture cannot be ruled out. Should the military-led government pair its pro-sovereigntist rhetoric with a more confrontational stance toward foreign investors, this could unsettle the business environment and cast doubt over existing commitments.

While less likely, this scenario remains plausible considering recent diplomatic moves and concrete initiatives like the envoy of arms and military personnel. Under this scenario, Russia could extend its sphere of influence in Africa beyond the Sahel region. Furthermore, both ongoing and prospective mining projects could face delays, renegotiations or even suspension, with broader repercussions for investor confidence and revenue projections.

Contact us today for tailored geopolitical insights and industry-specific advisory services.