How markets revealed the myths of central banking

Recent market performance has laid bare the goal of much monetary policy today: financing public expenditure. If inflation continues to recede, governments will find it more difficult to manage public debt.

In a nutshell

- Markets have defied predictions of an extended decline

- Investors emphasize public finance more than interest rates

- Smaller rises in prices will put more pressure on central bankers

Financial market pessimists have had a rough time over the past 15 years. The global financial crisis certainly provoked stock market crashes throughout the world; for example, the S&P 500 index fell from about 1,500 points in July 2007 to about 750 in March 2009. But it took only about four years to recover, and by January 2020 had reached 3,200.

Markets crashed again when Covid-19 sent waves of fear throughout the world (the S&P fell to 2,300 points in March 2020), but they rebounded to 4,600 in November 2021. A few months later, inflation, rising interest rates and the possibility of recession started to make headlines, but these also failed to make much of a market impact. In early July 2023, the index was at about 4,500 points. The record of the German DAX index has been similar, despite the German economy’s lackluster performance.

Predictions have been widely off the mark. The pessimists were not wrong to theorize that negative shocks would have consequences on financial markets; to point out that the public finance situation in many countries was fragile and would probably worsen, or to argue that the prospects for economic growth were dim due to increasingly heavy taxation and regulation. Nonetheless, financial markets have been celebrating all along.

Their only accurate prediction has been about the price of gold, the “safe haven” par excellence, which rose from about $670 per ounce in the summer of 2007 to $1,500 in March 2020 and $1,900 in July 2023. But, of course, those who put their money in stocks fared much better still than those who invested in gold (and much, much better than those who bought silver).

Perception and reality

Where did pessimists go wrong, and what can we learn from their mistakes? The answer is central banking. Before the global financial crisis broke out, central bankers used to claim they would shape monetary policy by targeting different variables: interest rates, consumer price inflation, money supply, nominal or real gross domestic product (GDP), employment, and so on. The narrative was rather confused.

Understandably, analysts and the informed public did not put too much faith in what central bankers announced they would do, and rightly so. The authorities might declare one target but, in fact, consider other objectives as well. Or they might indeed reveal the variables to be considered but remain vague about the threshold(s) that would trigger policy action.

The prevailing understanding was that monetary policy would consist of fine-tuning exercises when the economy was business-as-usual – and otherwise, of groping around in the dark. Nobody really knew how central bankers would react if a global shock hit. Accordingly, in normal times, investors would look at fundamentals and compare expected returns across various categories of assets, or perhaps resort to technical analysis (computerized buy/sell algorithms). And when potential trouble reared its head, they would run for safety.

After the global financial crisis, the perception of monetary policy changed. Investors have learned that the official targets play a lesser role (i.e., the fight against inflation should not be taken too seriously). Instead, public finance, and possibly commercial banking, should figure more importantly in analysts’ handbooks.

Read more by Enrico Colombatto

Reassessing the dollar’s global status

New model

Markets now doubt that central bankers care much about the supposed “modern purpose” of monetary policy (price stability), having rather reverted to its “original purpose”: financing public expenditure and public indebtedness. The focus on commercial banking is a by-product, since banks are affected – and are sometimes accomplices – in carrying out the policy driven by the public finance situation. Certainly, this new emphasis has consequences regarding interest rates. Yet the emphasis remains on public finance rather than on interest rates per se (or inflation).

When a shock hits the economy, two reactions follow. In the short run, unexpected news triggers the conventional reactions. A sudden drop in inflation, for example, means less uncertainty and possibly lower interest rates. Stock and bond markets rise, while the exchange rate of the domestic currency may weaken.

But after a few days or weeks, market agents will examine what this means for public finance. If the decline in inflation makes public debts lighter and more easily manageable, then the short-run effects are magnified. If the changes haven’t lightened the public debt load, celebrations turn out to be a flash in the pan.

Facts & figures

Scenarios

One can now use these simple mechanics to explore where recent and forthcoming news may take us. Different scenarios can materialize, depending on the nature of the possible shocks. This report considers two of them.

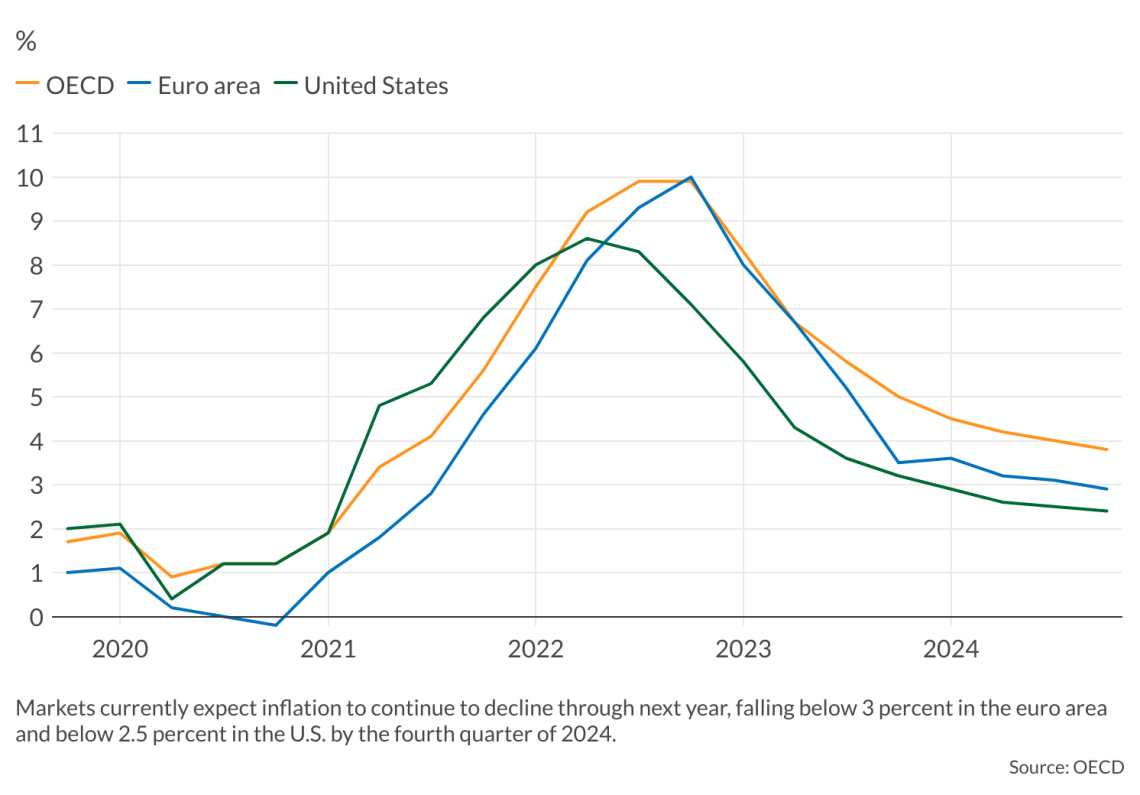

The base inflation rate and the core inflation rate were 3 percent and 4.8 percent in the United States (June 2023) and 5.3 percent and 5.5 percent in the eurozone (July 2023), respectively. In early July, markets expected a slow decline in the rates of inflation in both areas. Yet, whereas the Federal Reserve believes that inflation is now more or less under control, the European Central Bank (ECB) seems to be maintaining a more aggressive approach. Markets now expect rates of inflation in the U.S. and the euro area to drop to about 3-3.5 percent by the end of this year, and to less than 3 percent by the end of 2024. They might reach 2 percent in 2025, possibly later.

If prices fall as expected, whether governments can deal sustainably with public indebtedness will be determined by real growth and by their budgetary discipline – driving financial markets accordingly. Notably on this point, markets currently expect government expenditures to remain high in Europe (they stood at 50 percent of GDP in 2022) and to probably rise in the U.S. (from 37 percent of GDP in 2022).

In 2023 and 2024, therefore, the burden of public indebtedness is expected to stabilize in the euro area and rise further in the U.S. Under this first scenario, if these expectations play out, financial markets will remain generally stable. Stock markets may present some volatility, but no clear trend.

Of course, investors’ willingness to hold euro-denominated bonds with very low returns, in real terms, will play a key role. Trouble could surface once the inflation rate approaches the 2 percent benchmark. The inflation tax would then be small enough for more investors to move away from bonds (and treasuries) into stocks, or to increase their liquidity. ECB President Christine Lagarde and national governments would then be pressed to beg (or “encourage”) commercial banks to transform that liquidity into government bonds, regardless of what the public finance picture demands. The outlook could be even more difficult for Fed Chair Jerome Powell.

In other words, as inflation recedes, the inflation tax also recedes – and the new problem could be scarce liquidity and fewer buyers of government bonds. How will central bankers react? Do they have a plan, or will they cast this as one more “transitory” problem that nobody had seen coming?

A different scenario could materialize if growth picks up significantly. This could be the case if international tensions ease, or regulatory pressure to combat climate change subsides. Global growth could benefit from increased trade flows, lighter taxation and less oppressive regulation. Stock markets would naturally celebrate (at least in the short run), but central bankers and public debt managers would also feel relieved – the key dynamic to understanding the medium-term consequences.

In this scenario, debt-to-GDP ratios could stabilize even with interest rates significantly higher than those experienced in the past 15 years and may encourage a pause in interest rate manipulation, at least for a while. This would be good news for the economy in general and prospective bondholders in particular. Stock markets addicted to negative or low real interest rates would, however, be disappointed, and some long-overdue cleaning would take place. Good stocks would be rewarded, overly indebted companies would face severe trouble, and all those who bought long-term bonds in the past would take a beating.