The EU’s endemic migration crisis

Escalating migratory pressures will bring enduring political and socioeconomic challenges to the European Union.

In a nutshell

- Conflict and insecurity will drive millions of migrants toward Europe

- The EU has pledged to act together on political and economic effects

- But words have not yet translated into action

This report is the second in a two-part series on migration from GIS Expert Dr. Federica Saini Fasanotti. The first part, which was published yesterday, focused on the rise of climate migrants.

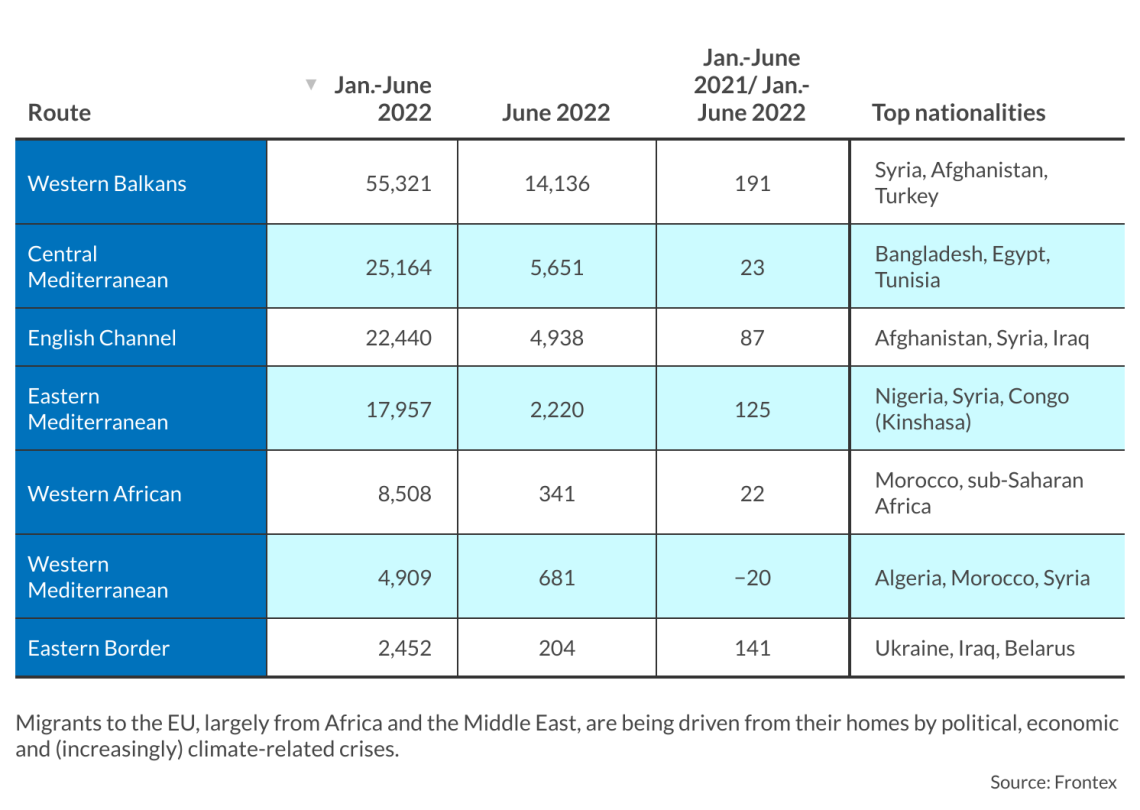

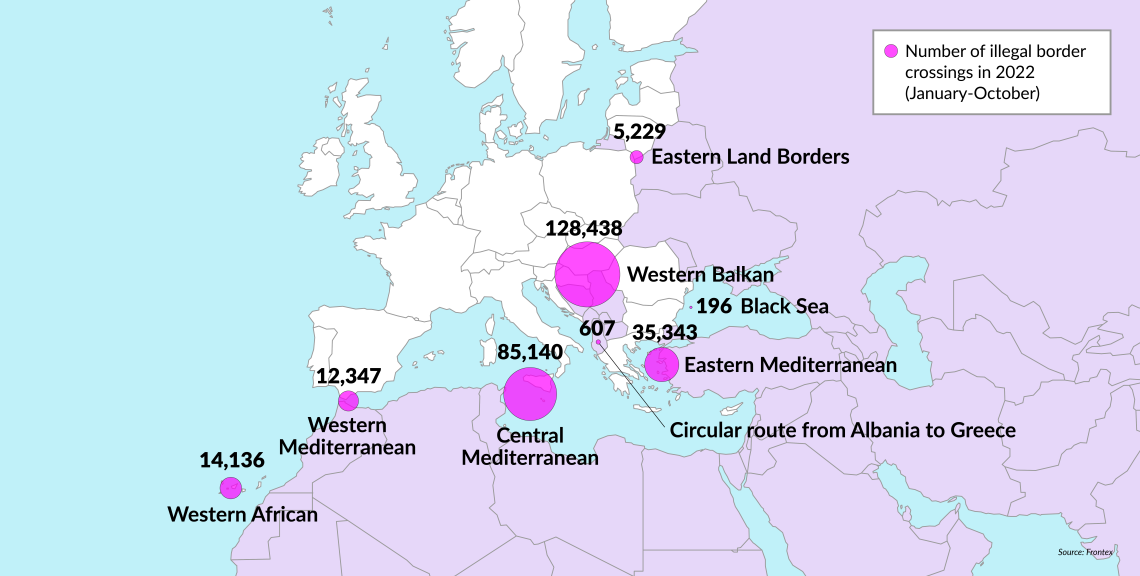

Figures published by European border security agency Frontex in July suggest significant challenges lie ahead for the European Union over migration. In the first half of 2022, Frontex counted 114,720 irregular entries into the EU, 84 percent more than in the same period last year. These figures do not include refugees from Russia’s war in Ukraine, which pressed some 7.2 million to flee to the EU since the start of the conflict in February.

From January to June, the EU saw increased migration flows along several routes, including the Western Balkans (up 191 percent from last year), the Eastern Mediterranean (up 125 percent) and the Central Mediterranean (up 23 percent). Despite the Brexit decision, partly made to address migration, there are also substantial numbers of migrants still seeking to illegally cross the English Channel into the United Kingdom.

Facts & figures

Europe is not facing the crisis of 2015, with nearly a million migrants landing on its shores and more than 3,500 known deaths (certainly a small fraction of the actual number of tragic casualties). Yet the 2022 numbers still do not bode well. The food crisis triggered by Russia’s illegal grain blockade of Black Sea ports this summer has added to the already urgent problems facing many developing countries.

Today’s significant migration numbers indicate a threefold crisis:

- The local, regional or national crises that prompt migrants to leave their homelands

- The social crises that illegal immigration will unleash in the transit and receiving countries

- The political crises sure to develop in receiving countries, as illegal immigration fuels populism, nationalism, and the emergence of illiberal or authoritarian regimes

Problems at home

To understand the first issue, one can look to the tragedy of Afghanistan after the collapse of the American-backed government in Kabul, or the implosion of the Syrian state, or continuing conflicts in several African territories. Groups of migrants from these areas, sometimes termed economic or political migrants, are nothing new. But another, more recent group will almost certainly overtake these in the not-so-distant future: climate migrants.

The shift has already begun, not only in Africa but around the world. Scientific data on climate change is alarming and may have an even broader scope than at first impression. Climate shocks will have massive consequences for the world’s weak and vulnerable, affecting already fragile African societies especially. According to the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the effects will be more severe than expected.

An increase in tensions, war and conflict – already widespread throughout the African continent – will be the primary outcome. Militias and armed groups competing with the state have long proliferated, driving instability. The problem is already acute: in 2022, an estimated 30 million residents of the Sahel region needed food, water or medical aid. Conflict and insecurity have driven more than 6 million people to leave their homes in search of refuge and a new life.

Despite its good intentions to reform migration and asylum rules, the EU is distracted by more seemingly pressing problems.

In this regard, the crisis has never been more pronounced than in 2022. The worse the situation for these populations – who are already struggling from political dysfunction and economic distress – the more emigration will become the way to survive on a continent that has for centuries been accustomed to it. Add to this exponential population growth: the Maghreb alone, which in 2019 had about 195 million inhabitants, will have about 231 million by 2050. Indeed, Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia are historically an important migratory basin to Europe, with emigrants making up 4.5 to 8.6 percent of their total population.

Population growth means more demand for coastal resources, which will already be affected by rising sea levels. At the same time, extreme heat and more frequent dust storms will have profound consequences on agriculture and air conditions, in turn shaping everything from food security to basic human health. The ultimate result, as areas in Africa become “uninhabitable,” is that substantial numbers of people in certain regions will be forced to migrate, adding to the population on the move.

In 2019, an estimated 6 million Africans were living in Europe and 3.3 million in the Gulf countries. By 2050, the African population could account for a quarter of the entire world population, with its 2.5 billion inhabitants. Given these numbers, the populist and nationalist drifts of certain European politicians may turn out to be nothing more than meaningless words.

Where does the EU stand?

In September, European Parliament President Roberta Metsola, Civil Liberties Committee Chair Juan Fernando Lopez Aguilar, Asylum Contact Group Chair Elena Yoncheva and permanent representatives from the Czech Republic, Sweden, Spain, Belgium and France agreed to conduct negotiations to reform the EU’s migration and asylum rules by February 2024. This step reinforces the European Commission’s proposal in September 2020 for the new Pact on Migration and Asylum to improve procedures, share responsibilities fairly among member states and act together in managing migration flows.

However, actions have so far not lived up to words, considering developments like the French withdrawal from Mali after a decade of military operations that saw over 3,500 soldiers deployed across Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania and Niger to stem violent jihadism. That retreat has left room for other countries, primarily Russia, a party hardly concerned with the welfare of African citizens, or those of European citizens. This is confirmed by the widespread presence on the continent of the Wagner Group. They are joined by China, Turkey and the Gulf powers – albeit in more official roles, but still ones with political and economic implications.

At the same time, it is possible to observe an authoritarian movement in many African states, especially in the Sahel area, which has seen as many as five coups d’etat since 2020, most recently in Burkina Faso. Many observers now believe that the departure of the Franco-Western garrison will leave more room for systematic violence against civilians – as demonstrated by the Wagner Group both in Mali and in the Central African Republic – and, consequently, an increase in jihadism spurred by public discontent.

In the Maghreb, there is a fragmentation of power that renders states particularly fragile, as the example of Libya shows. On top of malaise over an increasingly unsustainable political situation, Libya is also where a good portion of the migratory flows from Saharan and sub-Saharan Africa arrive.

But in the absence of authority by local governments, thousands of migrants pay a steep price in seeking to leave their lands. According to the UN Under-Secretary-General for Political and Peacebuilding Affairs, Rosemary DiCarlo, at least 2,661 migrants and refugees are imprisoned in Libya in detention centers – usually managed by local militia groups – with limited humanitarian access. Many are abused or even killed arbitrarily. These issues have been ongoing for years with no improvement, not least due to inaction from the EU.

Scenarios

Despite its good intentions to reform migration and asylum rules, the EU is distracted by more seemingly pressing problems, like the flow of legitimate refugees from Russia’s war in Ukraine. The EU will thus likely fail to devote enough time to draft and (especially) implement common policies capable of dealing with illegal migration.

The expectations of individual member governments vary, as was also on display during a Luxembourg meeting of national interior ministers held in June. There, a plan was discussed for a voluntary solidarity mechanism whereby migrants rescued in the Mediterranean would be taken in by willing states, while the others provide financial assistance linked to the costs of reception.

However, it is highly unlikely that countries such as Hungary and Poland will agree to such a proposal, even if it is a small step forward in European reception policy – perhaps motivated by the Ukraine crisis, which has seen millions of refugees heroically housed by different EU members.

In the meantime, migration flows will not stop, although winter will bring a slowdown in Mediterranean crossings, if not a halt. Politicians are already speculating about migratory flows – Italy is a prime example – but how much the European leadership will be able to alleviate the problem is another matter. Meanwhile, extreme weather is becoming more frequent in Africa.

Climate change is putting unrelenting pressures on numerous African countries, and at some point, the intracontinental migratory movement will explode along the various migratory routes into Europe – profoundly changing its political, social and economic equilibrium. Even if the EU does all it can to deal with migratory flows, it will still have to face the fundamental causes of emigration itself: conflict, economic decline and the juggernaut of climate change.