Winners and losers from the Karabakh war

The latest conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh has profoundly altered the geopolitical landscape of the South Caucasus. Turkey has become a serious contender for regional hegemony, but Russia will also attempt to boost its status by reviving some of the Soviet-era infrastructure.

In a nutshell

- The latest Karabakh war has transformed the region

- Russia and Turkey will compete for hegemony

- The West has been sidelined

A year has passed since the second Karabakh war transformed the geopolitics of the South Caucasus. The immediate outcome of the 44-day conflict was a triumph for Azerbaijan. When Russian intervention achieved an armistice, on November 10, Baku had succeeded in recapturing large swathes of land long under Armenian occupation. Given its decisive support for the Azeri war effort, Turkey also came out as a winner, challenging Russia’s status as a regional power.

Somewhat paradoxically, the outcome may turn out to be a boon for Armenia in the longer term. During the first Karabakh war, fought around the time of the collapse of the Soviet Union, Yerevan succeeded in capturing Azeri territory that surrounded the largely Armenian-inhabited Nagorno-Karabakh enclave. Despite being internationally recognized as part of Azerbaijan, the latter was de facto united with Armenia. The ensuing stalemate would become the archetype of a frozen conflict.

Unexpected opportunities

For Armenian nationalists, it was a major triumph. But victory came at a steep price. The borders with Azerbaijan were closed, as was Armenia’s border with Turkey. This left only Georgia and Iran, which was vital in supplying energy and other critical goods.

The frozen conflict disrupted the Soviet-era transport infrastructure, mainly by choking off the artery from Russia along the Caspian Sea across southern Azerbaijan onward to Turkey and Armenia. This mainly benefitted Georgia, which could offer a bypass option for transport from the Caspian Basin to Turkey.

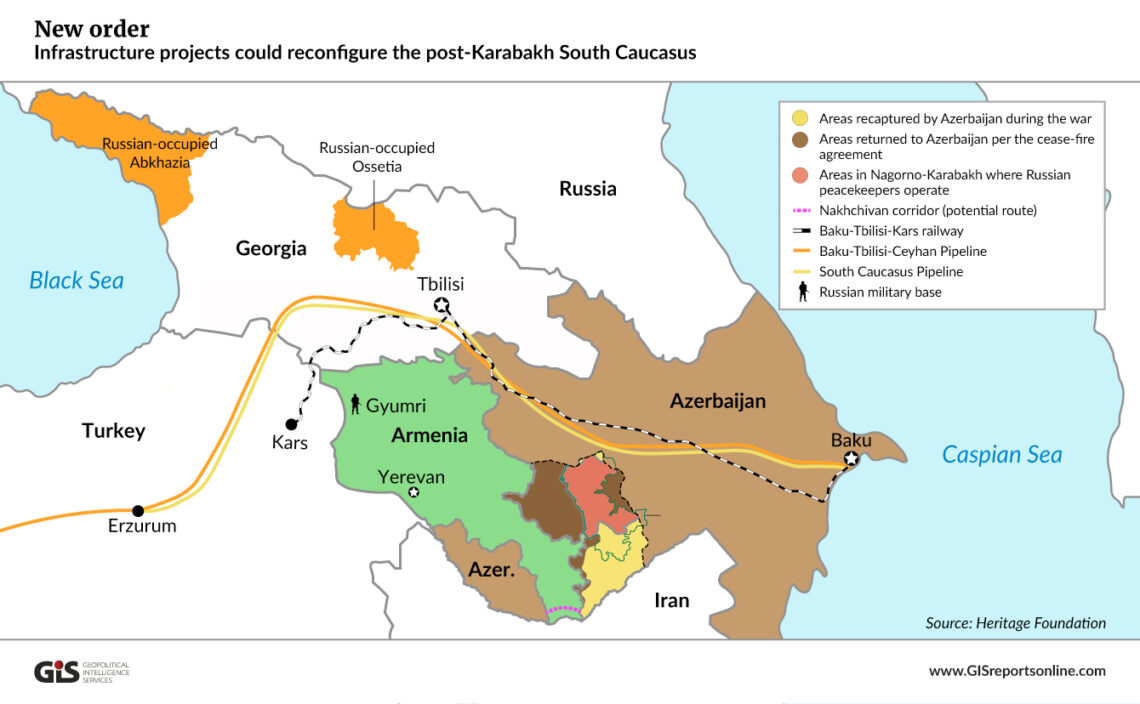

Later, pipelines for oil and gas were built from Baku via Tbilisi and onward to Turkey. Inaugurated in 2005, they were followed in 2017 by the Baku-Tbilisi-Kars railway line, providing an alternative to the closed railway from Tbilisi through Gyumri in Armenia to Kars in Turkey.

As the pipelines also bypassed Russia, Georgia became an enclave of Western favor. It received much support for its reform process, notably for fighting corruption. The United States trained Georgian troops, and Tbilisi sent soldiers to both Iraq and Afghanistan. The country appeared poised to join NATO and the European Union.

Facts & figures

Reconnecting the region

Following the second Karabakh war, the Soviet-era transport infrastructure could be reconnected. Reopening border crossings between Armenia and Azerbaijan may enable trade and development in border areas. Hopes for such revitalization are boosted by recent construction activities on both sides, putting to shame early fears that the areas devastated by war would become empty and barren.

The recapture by Azeri forces of territory along the border with Iran is of even greater significance. As part of the armistice, Armenia agreed to a transport corridor across its southern Syunik region, which may prompt three important developments. One would be to reconnect mainland Azerbaijan with its Nakhchivan exclave, landlocked between Armenia and Iran. Another would be to allow Turkey direct access to the Caspian Basin, via a tiny but crucially important corridor into Nakhchivan, and onward to Azerbaijan. And the third would be to reconnect Russia with Armenia.

If these projects are realized, Armenia could make major economic and political gains. Recent developments between Yerevan and Ankara suggest that Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan may feel he has so much to gain from getting access to the Caspian Basin and that downplaying the long-standing conflict with Armenia is a small price to pay. And if Yerevan’s conflicted relations with Turkey and Azerbaijan are defused, it will be less dependent on Russian protection, which has so far reduced its scope for independent international ties.

If Armenia becomes a regional transport hub, it will be to the detriment of Georgia.

If Armenia does succeed in emerging as a regional hub for transport of both goods and people, it will be to the detriment of Georgia. The pipelines and railway lines that cross its territory will remain important, but its strategic role in bypassing Armenia will be greatly undermined. The Baku-Tbilisi-Kars railway constitutes a case in point. As the new transport corridor across Armenia will be about 340 km shorter, it will decrease transport costs and boost bilateral trade between Azerbaijan and Turkey without involving Tbilisi.

If Russia, finally, succeeds in revitalizing the transport artery through Azerbaijan and into Armenia, it will have a viable alternative to the Soviet-era transport corridor south through Georgia. It will also mean Tbilisi will have insufficient leverage to deny Russia the right to transit troops to its base in Armenia.

All of this happens at a time when several other international developments have already played to Georgia’s disadvantage. The Kremlin has been consolidating its grip over the Georgian breakaway regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. It has offered them recognition as sovereign states. It has invested in border demarcation and border security – deep inside Georgia – and formalized rules on dual citizenship.

Following its “pivot to Asia,” the U.S. has been largely absent from the region. It was deeply symptomatic that the armistice in the Karabakh war was negotiated by Russia. Having spent three decades looking for a negotiated solution, the OSCE Minsk Group was nowhere to be seen. In the words of Armenian political expert Benyamin Poghosyan, the group “will continue to adopt useless statements that will have zero impact on the situation.”

The American debacle in Afghanistan has emphasized Georgia’s isolation. And the EU has not been shy about driving home its “fatigue” over the seemingly chronic gridlock in Georgian domestic politics, including the recent return and incarceration of former president Mikheil Saakashvili.

Hurdles and quandaries

Further developments will be determined by how the regional great power rivalry plays out. Russia’s vision is a 3+3 cooperation format that involves the smaller countries – Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia – together with the great regional powers – Iran, Russia, and Turkey. No mention is made of either the U.S. or the EU.

At a meeting with Iranian Foreign Minister Hossein Amir-Abdollohian in Moscow in early October, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov said that the three “big neighbors” agreed on what steps were needed to advance the Karabakh armistice agreement, namely, “unblocking all transport communications, unblocking all economic ties in this region, from which not only Armenia and Azerbaijan but also Georgia will benefit.”

A substantial hurdle is a need for border demarcation between Azerbaijan and Armenia, a highly fragile process that may entail territorial swaps. Skirmishes are still ongoing. The exchange of prisoners remains to be completed, and there is much bad blood on the Armenian side. With troops present in contested areas, the Kremlin may still be expected to manage the situation. Intransigence from Armenia may be countered by a threat of allowing Azerbaijan to resume its offensive.

But the real prize in the geopolitical game remains the unblocking of the Nakhchivan Corridor, known in Azerbaijan as the Zangezur Corridor. Existing railbeds and tunnels have fallen into serious disrepair. While upgrading the stretch that runs through recaptured Azeri territory will be handled by Baku, it is unclear who will manage construction on Armenian territory. There is widespread Armenian opposition to a corridor that is outside its control, and there are fears that an inflow of capital from Turkey and Azerbaijan may further undermine the country’s sovereignty.

The most likely scenario is that the Kremlin will successfully promote the unblocking of broken infrastructure links.

Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan is in a real quandary, being forced to weigh prospects for economic development against potential threats to national sovereignty. He survived the Karabakh defeat, winning a resounding victory in June 2021. Claiming to have a popular mandate to bring about “an era of peace in the region,” he has called on Armenians to have “strong nerves.” Control over the corridor will be in the hands of Russian border guards. Acting as protector of Armenian interests, the Kremlin may well be successful in working with Yerevan to alleviate distrust.

Iran views the Nakhchivan corridor as a threat. One reason is that Turkey expects to use it as a bypass, reducing its dependence on the transit of goods via Iranian territory to markets in Central Asia. The corridor would significantly reduce Tehran’s leverage over Ankara. Another more serious issue is that relations between Iran and Azerbaijan, never good to begin with, have deteriorated considerably.

Foreign Minister Abdollohian has noted that Iran is “dissatisfied” with the actions of “one neighbor,” and emphasized its long-standing concern about military links between Azerbaijan and Israel: “We will not tolerate geopolitical and map changes in the Caucasus. And we have serious concerns about the presence of terrorists and Zionists in this region.”

Scenarios

Russia wants a north-south transport corridor via Azerbaijan and Iran to seaports on the Indian Ocean. But this competes with the parallel Iranian vision of a corridor through Armenia that links seaports on Georgia’s Black Sea coast with the Iranian seaport at Bandar Abbas on the Persian Gulf. The latter option would benefit Armenia and even more so Georgia, increasing its likelihood of becoming integrated also in the rollout of the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative.

There are severe logistical challenges. There is no direct railway between Armenia and Iran, and the M2 highway that carries the bulk of traffic between the two countries and onward to Georgia is not only in bad condition. It is also at high altitude, making winter use difficult. Even worse, the settlement of the Karabakh war has caused a part of the M2 highway – a 20 km stretch between the cities of Goris and Kapan – to come under the control of Azerbaijan.

There have been several incidents where Iranian truck drivers have been detained at newly introduced border controls. These issues coincided with Iranian military exercises along the border with Azerbaijan. Ominously, those drills followed a series of military exercises inside Azerbaijan, involving Turkey and Pakistan.

The most likely scenario is that the Kremlin will successfully promote the unblocking of broken infrastructure links, including the resolution of border issues between Armenia and Azerbaijan. Given that the most obvious winners will be Azerbaijan and Turkey, and possibly Armenia, it is doubtful how much Russia will stand to gain. While the Kremlin may be happy to see Georgia on the losing side, it will also be forced to manage increasing antagonism from Iran. If its own main achievement in acting as regional hegemon is set against the growing clout of Turkey, the longer-term net outcome may even turn out to be negative.