The age-old nature of the ‘new Cold War’

Russia’s war in Ukraine and the rise of China signal an ideological challenge to the Western order, of the kind thought buried with the Soviet Union.

In a nutshell

- The ‘end of history’ thesis is dead

- China has seized on the shortcomings of liberal democracy

- The West’s response could intensify the conflict

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is the latest and most potent indication that history is back, and with a vengeance. Contrary to proponents of the “end of history” thesis, the ideological struggle of the 20th century between what used to be called the “free world” versus “the Marxist-Leninist” camp is ongoing, despite the conclusion of the Cold War. This continuing struggle now pits the United States-led, Western alliance system against a China-centric global network of nations, including Russia, that display shades of authoritarian governance.

While the Soviet Union put up (and lost) the first ideological fight, China as its logical successor, and Russia as its residual state, are now engaged in a second round. Its conclusion will depend on how China exercises its emerging power, and how the U.S.-led alliance system responds.

The liberal moment

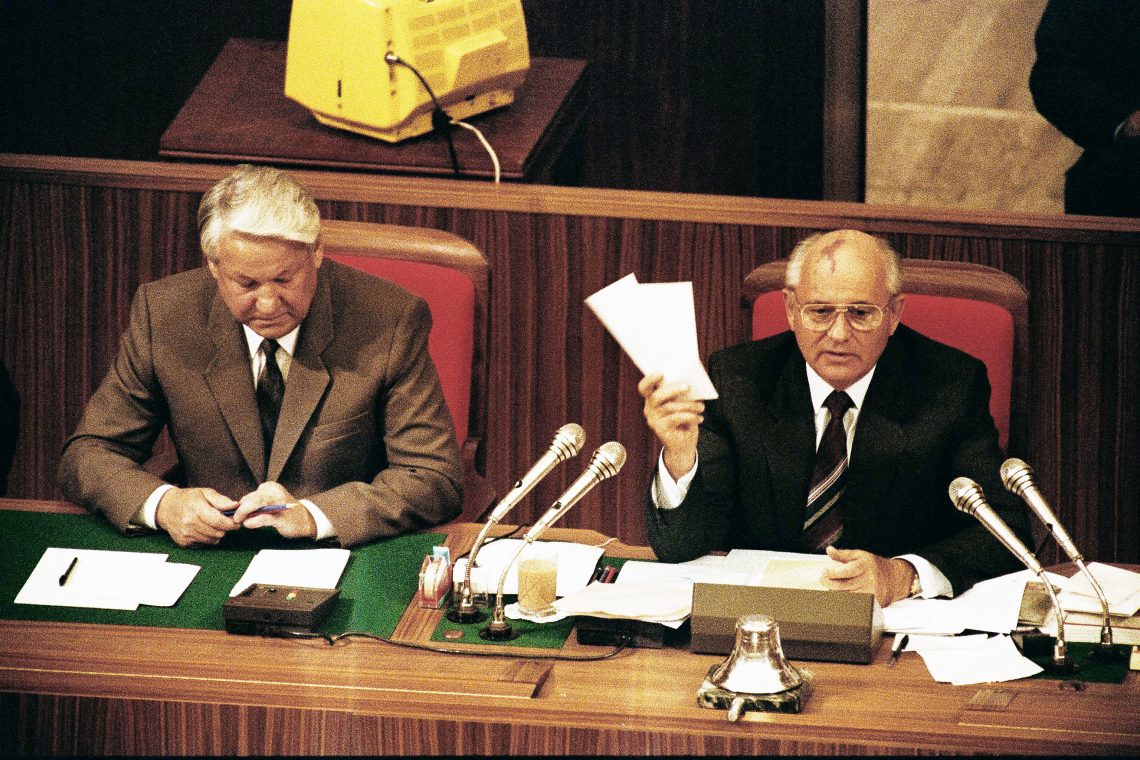

When the Soviet Union collapsed, it was argued that history as we knew it had come to an end. Francis Fukuyama’s landmark article in 1989, and his book by the same name three years later, reflected what many thought was taking place: somehow, the dialectical history of ideas about organizing societies and economies had reached a denouement.

At the time, it seemed Western liberal democracy and market capitalism had indeed triumphed as the best and most self-sustaining system of government, social arrangement and economic management in history. It defeated the Soviet Union’s political totalitarianism, economic central planning and social egalitarian pretensions because the logic of the market, capital, liberty and democracy was ultimately too powerful.

Democratization was making headway and market capitalism becoming the dominant paradigm for economic growth.

In the immediate aftermath of the Cold War, it seemed that the U.S. had a “unipolar” moment to reshape the world order. The ensuing two decades, roughly 1990-2010, were initially marked by the spread of markets and democratization in much of the developing world, including in the formerly Soviet-controlled Eastern Europe. The European Community led the way in liberalization by realizing the European Union, with converging foreign and security policies and a common currency.

Elsewhere, democratization was making headway and market capitalism becoming the dominant paradigm for economic growth and development. These trends prevailed despite global volatility and limited conflicts in many parts of the world, including the breakup of the former Yugoslavia and the transformation of former Soviet satellites into independent states.

Losing ground

While the early 2000s witnessed the U.S.-led “global war on terror” and militant Islamist expansionism, liberal democracy and market capitalism continued their march. Yet over the past decade or so, democracy and capitalism have come under stress. In many places, the promise of freedom and prosperity has fallen short. Capital and wealth have increasingly accumulated in the hands of a few, while certain liberties have led to societal divisiveness and polarization. Democratization has suffered from a rollback, giving way to resurgent authoritarianism in a host of countries.

As citizens became more disillusioned with the disappointing results of democracy and capitalism, exacerbated by globalization and technological advancement, many sought alternatives. Populism and authoritarian varieties of governance attracted those resentful of being left behind financially. Populist leaders connected directly with the masses and bypassed established centers of power such as the media and entrenched political classes – pitting the masses against the elites and weakening the social and political fabric of democratic, capitalist societies.

Enter China. Its allure thrives on the shortcomings of democracy and capitalism. Its model of top-down “authoritarian capitalism” is still Marxist-Leninist, but with a twist: its “democracy” is limited to inside the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), comprising a single-party state rather than a multiparty democracy as in the West. China exhibits centralized political control in a totalitarian fashion, yet its economic development and management are market-consistent, if not market-driven as such. China thus frustrates the Western model of liberal democracy and market capitalism in novel ways.

China’s challenge

The ideological battle that Marx started did not end with the Soviet demise, but rather continues with China’s rise and resurgence. Having just celebrated the CCP’s 100th year, communism is alive and well in China, but with capitalist characteristics. The inherent contradictions of political totalitarianism and market capitalism make China simultaneously strong and weak. No other modern state has been able to have its cake and eat it too: imposing centralized political control at the expense of rights and freedoms, while running an economy that delivers better lives and standards of living for its people.

The CCP-ruled Chinese state leads and drives a capitalist economy in the way that Japan, South Korea and Taiwan pioneered in the 1960s-1980s. The difference is that these three Asian countries were strong U.S. allies, irreversibly becoming Western-style democracies; China is not, and never will be. In this way, China is trying to steer away from the West’s flaws of concentrated wealth, political polarization, and societal dysfunction.

The Soviets lost without a real fight; the Chinese are likely to put up one, because they will not accept losing.

Moving forward, China’s approach to being a superpower is likely to reshape the global system to its preferences. The new Cold War is, structurally, age-old: it continues the previous confrontation of the last century, with a new chapter. Then, the Soviet Union confronted the U.S. directly in proxy battlegrounds in the developing world, but eventually lost because it could not keep up with the more dynamic Western-centric capitalist development. The Soviets did not lose militarily, but economically.

China, on the other hand, has not been confronting the U.S. directly in military terms, despite its huge arms buildup. China’s direct and aggressive pushback takes place on trade protectionism and technological innovation. This face-off between the new and old East (China and Russia) on the one hand, and the old West on the other, would in the best-case scenario be solved through compromise.

That would see China accorded a role befitting its global weight and pride, and Russia retaining commensurate imperial dignity and security guarantees from an expansionist European Union and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. If denied and suppressed, both China and Russia will likely feel resentful and agitated. The Soviets lost without a real fight; the Chinese are likely to put up one, and with Russia at their side, because they will not accept losing.

Scenarios

Round two of this old Cold War with new characteristics can lead to three potential outcomes. First, if the U.S.-led and Western-centric alliance system fails to accommodate China, tensions will likely intensify and lead toward confrontation and conflict. While China’s intimidation and threats against Taiwanese autonomy is a major potential flash point, Beijing’s maneuvers in the South China Sea – where it has staked out rocks and reefs and turned them into militarized islands – will continue to threaten the security and economic interests of the Philippines and Vietnam, U.S. allies and strategic partners, respectively. Tensions over China’s high-tech innovation and acquisition and its rising protectionism may also spill over from geoeconomic competition to outright military confrontation.

Instead of conflict, the U.S. and China could also arrive at mutual respect and accommodation. This second scenario is premised on China’s projection of power within its sphere of influence under the Belt and Road Initiative, covering much of the Eurasian landmass up to Russia’s strongholds as well as parts of Africa. This would be a so-called “G-2” setup. A decade ago, most countries were afraid of G-2 because it would virtually divide up the globe into two main geostrategic swathes under the two superpowers. But as confrontation and conflict between them loom, such an arrangement may well again find appeal.

The third scenario is attrition between the U.S. and China. While their geostrategic rivalry and competition continue to heat up, it remains manageable, with off-ramps and reciprocal, timely backdowns from both sides. The two superpowers would maintain their seesaw competition, reinforced by economic interdependence and nuclear deterrence on each side, without degenerating into military conflict.

While the second and third scenarios are universally beneficial, the first outcome of confrontation and conflict would fit past patterns of interstate relations. It is not just the repeat of history that beset the U.S.-China rivalry. More to blame is the structure of an international system dominated by inherently distrustful nation-states, in which only one can be at the top.