The rise of China and the future world order

For Washington, Beijing presents both economic and military dilemmas. As China tries to replace the United States as the global leader, countries that benefit from the current world order can help by taking on a bigger share of the burden for maintaining it.

In a nutshell

- China still benefits from American hegemony

- It cannot afford to take the U.S.’s place yet

- The U.S. could survive this challenge with burden sharing

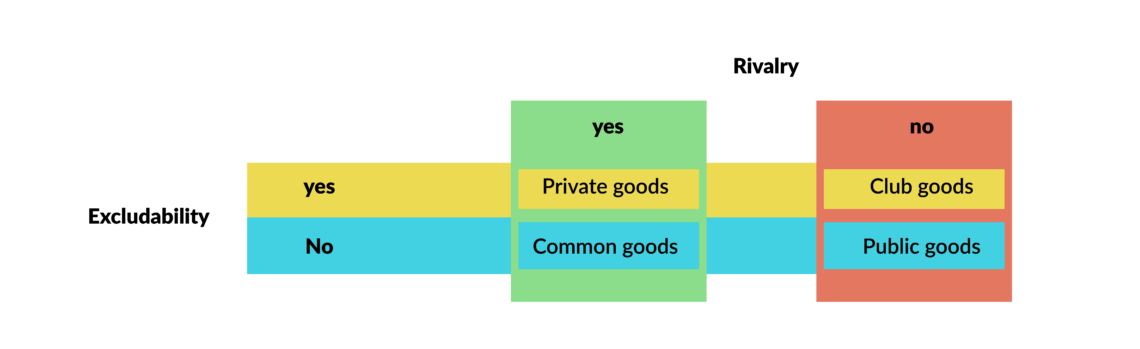

China’s rise to economic leadership has fundamental consequences for the future world order, which the theory of goods can help us understand. Within its borders, the state has a monopoly on the use of force and performs its regulatory function by providing public goods. Public goods are those that meet the criteria of non-rivalry and non-excludability. If there is rivalry and excludability, these are private goods for which the market is responsible.

Take a traffic light. No user of the road can be excluded, and use by one does not affect use by the other. It is therefore a public good. Public goods are financed by taxes and the state determines the rules of use – in this example through traffic laws.

Facts & figures

Goods theory

Then, there are two special cases. If there is excludability but no rivalry, these are club goods. One example is a sports club’s facilities, which are only available to members for unlimited use. They are financed by membership fees. The rules of use are determined by the club’s statutes.

If there is no excludability, but there is rivalry, the goods are common property. For example, no owner of a riverbank can be excluded from using the river, and this use comes at the expense of others. Regulating such goods is possible through conventions or treaties.

International public goods

Public goods within the international arena present a much trickier question. Here, too, there is a need for regulation. But who is responsible for international public goods? The countries of the world effectively exist in anarchy and there is no global state with an international monopoly on the use of force. Moreover, since there is no international taxation, international public goods are all provided for free.

The order in global anarchy results from the hierarchy of states. The great powers ensure this order by paying for international public goods and letting all others participate as free riders, because they have the greatest interest in them and are the only ones with the necessary resources to manage their use. For example, in the 19th century, one crucial kind of international public good was the lighthouse. Any ship could use it, doing so would not interfere with others using it, and the service was free. The lighthouse of the 21st century is the Global Positioning System (GPS), which is used not only by car drivers, but also by aircraft and ships worldwide. GPS is provided by the United States. Only the American taxpayers bear the costs.

The led accept the hegemon because it radiates soft power.

Because the reach of international public goods is unlimited, the power that provides them is hegemonic. International club goods are offered by an imperial power because their reach ends at the borders of the empire and they only apply to the club of those who belong to the empire.

The term hegemony comes from Greek and means leadership. It presupposes the acceptance of the led, which they give because they derive the benefits from the hegemonic order without contributing to the costs. They also accept the hegemon because it projects soft power, as expressed, for example, by the American way of life.

The term empire comes from the Latin imperium, which aside from “empire” also means “domination,” implying servitude. Accordingly, Athens was a hegemonic power in the Delian League, Rome an empire that secured its provinces by stationing legions in them. Nevertheless, it could be attractive to be a member of the empire because one could enjoy club benefits such as the Pax Romana.

The hegemon finances international public goods from its own resources because of its superior efficiency, while the empire finances international club goods through the tribute it demands from the subjects. That is why empires must be leaders in military terms, and why hard power takes precedence over soft power.

Securing the global order

The rise of great powers is triggered by innovations of all kinds. A classic example is the Mongols’ “cavalry revolution,” which they used to conquer a large swath of the Eurasian landmass. Under the protection of the Pax Mongolica, permanent contacts between China and Europe were established on the Silk Road, marking the beginning of globalization.

Hegemonic powers must be innovative in many fields, on land and sea – and more recently, in the air, in space and on the internet. For this reason, empires tend to be land powers and hegemonies sea powers. Imperial rise occurs in the wake of conquest as rapidly as imperial decline occurs as a result of overextension, when the imperial effort (the cost of conquest and occupation) exceeds the imperial benefit (the raising of tribute). Hegemonic rise is gradual, like hegemonic decline, which sets in when laggards become more innovative, able to engage in cutthroat competition but not having to pay the hegemonic costs. The Cold War can be read as a conflict between the U.S. as a hegemonic power and the Soviet Union as an empire.

Great powers have the option of withdrawing from the world and refusing to pay for international goods because they can be self-sufficient, leaving the rest of the world to anarchy. China and the U.S. have both engaged in this type of isolationism. Small countries are not able to do this; they need international exchange and an international order that they cannot provide themselves.

The global order has been determined by great imperial or hegemonic powers for about 1,000 years. The most important goods provided were security and stability. Security means military security, as guaranteed by the Mongol cavalry on the caravan routes or the British fleets enforcing the principle of freedom of the seas on the international commons of the oceans. Stability means stable economic relations guaranteed by trade treaties, international means of payment and credit, standardization of norms, weights and measures, a lingua franca for business transactions, and so on. At the time of the Pax Mongolica, the Italian merchants were responsible for stability, the Mongols for security.

According to this view, the world order is only ensured when great powers are strong and engaged. But what happens during periods of transition when one great power is descending, and another is ascending? Does the anarchy of the world of states then return? Is it a transition between two hegemonic powers or between hegemony and empire?

A transition between two hegemonic powers is more likely to be peaceful, as from the United Kingdom to the U.S. after World War II. The second scenario – transition between hegemony and empire – is more likely to be violent, as with the French (under Napoleon) or German (under Hitler) attempts to conquer Europe and establish a new order. Can the old power hold its ground and go through a new cycle? Is there a third party lying in wait, like the U.S. during the conflict between the declining power of the UK and the rising power of Germany at the end of the 19th century?

U.S. power, Chinese rise

History provides examples of many variants. Most recently, we witnessed how the U.S. was presented with a double challenge – militarily by the Soviet Union and economically by Japan in the 1970s and 1980s. The Soviet Union eventually collapsed, and Japan was challenged by new economic competitors such as South Korea and China. This is why the U.S. has been able to go through a second cycle since 1990, establishing itself as the first global power in history.

Today, its aircraft carrier fleets guarantee freedom of the seas and global oil supplies, its nuclear umbrella protects even some non-NATO members and it acts as the global police in the fight against terrorism. It is a safe haven for capital and a lender of last resort, while the U.S. dollar is the dominant global currency. It founded the internet and exerts influence through the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. Last but not least, it brings its power to bear with the regulatory paradigm of neoliberalism and the Washington Consensus.

This familiar order has become fragile since China abandoned the isolationism of the Mao Zedong era in 1978. During the era of Deng Xiaoping, it gained economic power through reform and opening-up policies, achieving historically unprecedented growth of 10 percent annually over four decades. During the Xi Jinping era, it has made an unconcealed claim to leadership.

The successes of China’s model make it attractive to authoritarian systems worldwide.

China’s economy is much more robust than the Soviet Union’s and its military is much stronger than Japan’s of the 1980s. Unlike both, it looks back on a long history during which it considered itself the center of the world. By 2035 at the latest, it will have overtaken the U.S. as the world’s biggest economy, and by 2049, on the centennial of the People’s Republic, it wants to be the leading international power again.

The challenge is also paradigmatic, because with the Beijing Consensus, China is advancing the model of the bureaucratic development state. This formula demonstrates that growth, social change, a middle class with purchasing power and technological excellence can all be realized under authoritarian auspices – contrary to the Western message that these presuppose liberal democracy and a market economy. The successes of China’s model make it attractive to authoritarian systems worldwide in Asia and Africa, even in Eastern Europe, exuding a Chinese kind of soft power. There remains plenty of doubt, however, about whether the Chinese model can be exported beyond the borders of the Confucian cultures.

Under current circumstances, both opponents face a dilemma. In the case of the U.S., it is the dilemma between losing its position as a leading economic power and losing its status as a liberal regulatory power. If the U.S. were to react with protectionism and engage in trade conflicts with China to ward off further deindustrialization, it would lose its status as a leading liberal power. If it were to raise the flag of liberalism, it would accelerate its industrial decline until it no longer has the resources to maintain international leadership.

If Beijing tries to assume the U.S.’s role, it will also have to bear the costs.

President Donald Trump wanted to protect the industrial base and was prepared to give up leadership on liberal values. President Joe Biden has made the opposite choice. However, like President Trump, he is not prepared to tolerate the free riding of the allies any longer and is pushing for burden sharing.

China faces the dilemma of the free rider whose export-driven growth benefited from liberalism without sharing in the costs of international public goods. If the U.S. refuses to share those benefits, it will be at China’s expense. But if Beijing tries to assume the U.S.’s role, it will also have to bear the costs – and with worse results, because its power does not reach as far as Washington’s.

BRI strategy

China’s temporary way out of the dilemma is a two-pronged one. The 14th Five-Year Plan (for 2021-2025) speaks of two economic cycles – one export-driven and one aimed at expanding the domestic market by strengthening mass purchasing power. Thus, like the U.S. did under President Trump, China is playing the big country card. The second resolution of the dilemma is that it does not offer international public goods, but it does offer international club goods – namely for all countries that are willing to become members of the “club” of participants in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which was announced in 2013.

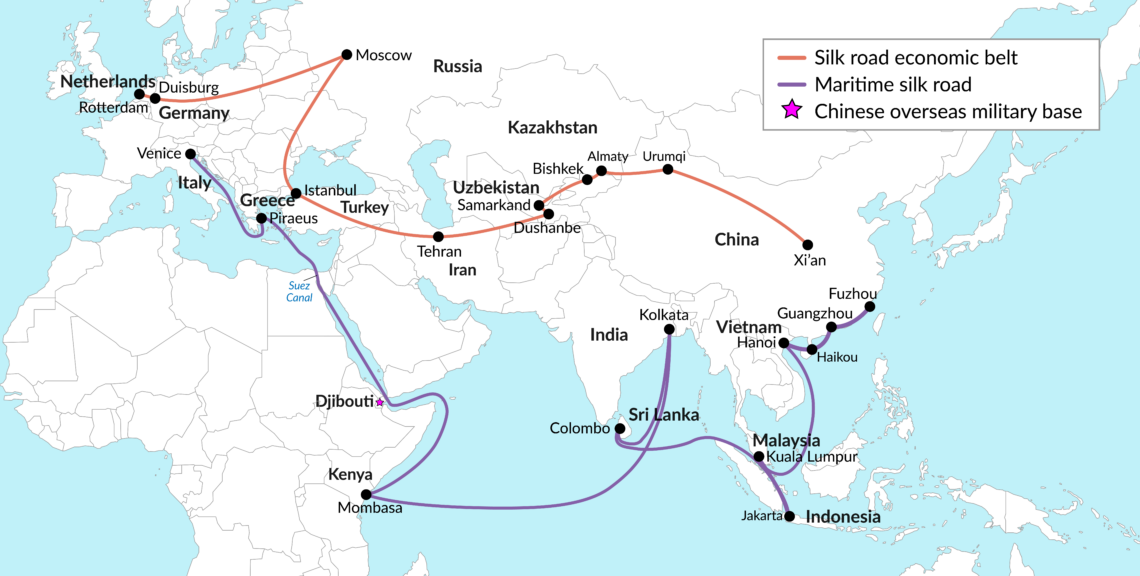

The main route leads from the Chinese coast through the territorial waters of the South China Sea, the Malacca Strait, across the Indian Ocean to the Red Sea, through the Suez Canal to Piraeus and Venice. From there, the journey continues by rail through the Balkans and the Gotthard Tunnel to Western Europe.

Facts & figures

China’s Belt and Road Initiative

Geopolitical activities are concentrated on this route. The construction of a carrier fleet is underway, airports on artificial islands in the South China Sea are in operation, a naval base in Djibouti has been leased, ports in Hambantota (Sri Lanka), Kyaukpyu (Myanmar), Gwadar (Pakistan) and the airport in Male (Maldives) have been built with Chinese help, and the ports of Piraeus and Venice have been bought in whole or in part. In terms of capacity among European ports, Piraeus is second only to Rotterdam and Hamburg. The route is vulnerable, however, as demonstrated by the container ship accident in the Suez Canal.

The alternative is the route around Africa. On this path, China has become active through its participation in port companies on the African east and west coasts, the so-called String of Pearls, and in Western Europe. Disadvantages are the longer travel time, sailing through waters threatened by pirates and higher costs. The shortest route would be the Northwest Passage, but that is still a pipe dream, despite climate change.

There are also two overland routes. Currently, the Trans-Siberian Railway is used to Moscow and from there on to Duisburg, Germany’s largest inland port. The advantage is the time saved compared to sea routes. The disadvantages are the lower transport capacity and the dependence on Russia.

The old Silk Road’s overland route would be the shortest connection, and China has therefore made reviving it the highest priority. It runs from Xinjiang province in western China, through Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Iran and Turkey to southeastern Europe. China is opening up completely new routes with the construction of trunk roads, railway lines, pipelines, power lines and communication lines. All this connectivity requires some coordination of timetables, harmonizing standards, veterinary and technical certification regulations, customs formalities, payment transactions, and so on.

For now, China is neither willing nor able to replace the U.S. as the leading global power.

Countries with coasts and access to water are lured by generous loans and modernization of their maritime infrastructure. Important players are the Chinese Ocean Shipping Company. (COSCO), which also runs port management, and China Merchants Port. China thus provides the club good of economic stability.

The club good of security is the BRI’s weak point. China is working hard to provide security on the sea routes but faces problems in parts of the land routes where statehood is fragile, as it does not have a global network of military bases. So far, there is only evidence of the deployment of “protection troops” for its investments in Pakistan. Here, collaboration within the framework of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation with Central Asian countries, Iran and Turkey is the alternative. The Chinese government is also trying to establish good relations with European Union accession candidate Serbia and EU members such as Greece, Italy, Hungary and Poland. Beijing is even using offers of the Sinovac Covid-19 vaccine to divide the bloc.

Sharing the burden

For now, China is neither willing nor able to replace the U.S. as the leading global power, because it is still inferior militarily (although it is catching up). Therefore, it wants to offer an alternative to the U.S. on the continental and maritime tracks between Asia and Europe. International organizations under Chinese leadership, such as the Regional Cooperation Economic Partnership (2020) for the Indo-Pacific region, also serve this goal – a clear rejection of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation, in which the U.S. plays a significant role.

What does this mean for the EU, for Western Europe, but also for Japan, South Korea, and other emerging Asian regions, especially Taiwan, which have so far been under the U.S. hegemonic umbrella? The change to the Biden administration has brought about a rapprochement between the previous free riders and the old leading power, even if the U.S.’s hegemonic dilemma has not been solved. There will be no return to the good old days when Washington took care of international public goods and did the “dirty work” in regions of fragile statehood, while countries like Germany could concentrate on social policy.

From a realist perspective, it follows that Europe must be prepared to share the burden of stability and security. In this way Europe, and countries around the world, can help support the U.S. in the hegemonic struggle with China.

The two alternatives to this scenario are not very pleasant. In the first, a future Chinese world order arises, oriented toward the bureaucratic development state and where the Communist Party in China calls the shots. In the second, the anarchy of the world of states returns for an extended period, in which government is not based on international public goods but on the principle of each country for itself, because the Sino-American conflict will drag on for the foreseeable future.