NATO’s Nordic bloc: Big promise, lurking problems

Finland and Sweden will add considerable military assets to NATO, but divergent policies can weaken the geopolitical impact of the Nordic bloc.

In a nutshell

- Moscow’s ability to project military power in Northern Europe is impaired

- Finland and Sweden will add cutting-edge military capabilities to NATO

- Sweden’s politics could make it an obstinate player in the alliance

The inclusion of Finland and Sweden into NATO now looks increasingly likely. There are still some remaining questions regarding ratification by Turkey (and perhaps by Hungary), but assuming those will be straightened out, what are the implications of the creation of a new Nordic bloc in the Western alliance?

First and foremost, it will remove the edge of the Kremlin’s posture toward the Nordic region. Moscow’s threats issued at the outset of the year about severe consequences if the two dared even to contemplate joining NATO have proven little more than hot air. When Russian President Vladimir Putin encounters determined resistance, he backs off, which is an important takeaway.

Nordic bloc’s potential

Looking beyond the Kremlin’s failure to prevent this outcome, the main questions concern what it will mean for the northern flank of NATO, now and in the future. Would the emergence of a coherent Nordic bloc make a difference in the West’s relations with Russia?

Facts & figures

Factbox: Europe’s Nordic countries

The Nordic Region consists of Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Iceland and Greenland, as well as the Faroe Islands and Aland.

Sweden is the largest and most populated Nordic country, with over 10.5 million inhabitants. It is known for its steelmaking and manufacturing capabilities. Historically an ambitious regional military actor, it presently takes pride in its soft-power prowess.

Norway sits on the western and northernmost parts of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The arctic island of Jan Mayen and the Svalbard Archipelago also belong to Norway. Synonymous with oil, fiords and mountains, Norway’s natural resources and highly developed economy offer its 5.4 million citizens one of the highest standards of living on the planet.

Finland, with a population of 5.6 million, is nearly two-thirds covered by thick woodlands and features more than 180,000 lakes. It forms a symbolic northern border between western and eastern Europe. Independent from Russia since 1917, the country rapidly industrialized and developed an advanced economy after World War II. It skillfully maintained a neutral political stance through the Cold War era.

Denmark, the southernmost of the Nordic countries, consists of the Peninsula of Jutland and an archipelago of 443 named islands. Of the 5.9 million inhabitants, some 800,000 dwell in the capital of the densely populated country.

Iceland, the volcanic island in the north Atlantic, independent from Denmark since 1944, is the most sparsely populated country in Europe (only 376,248 people lived there in January 2022). Known for its free-market economy, Iceland attracts tourists due to its hot springs and dramatic scenery. Despite its location just outside the Arctic Circle, the country is warmed by the Gulf Stream and has a temperate climate.

Greenland, the world’s largest island, is a district of Denmark. Its population (56,466 in 2022), concentrated mainly on the southwest coast, originates from Central Asia. Geographically, Greenland belongs to the North American continent, but geopolitically it is a part of Europe.

The Faroe Islands, a North Atlantic archipelago and island country, is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. Located about halfway between Norway and Iceland, the 1,400 square kilometer country has a population of about 54,000 (2022).

Aland, an autonomous and demilitarized region of Finland, is an archipelago of some 300 habitable islands (out of more than 6,000 rocky islets), located in the Baltic Sea between Sweden and Finland. Its population is about 30,000. Alanders speak Swedish and historically leaned toward Sweden.

The outlook rests on two baseline assumptions. The first is that once the war in Ukraine has ended, NATO will be faced with a long-term commitment to contain a weakened Russia that remains armed with nuclear weapons; the task will require significant resolve. The second is that unless the sanctions regime is lifted, Russia will be unable to rebuild its prewar conventional military capabilities, not to mention introduce new weapons or even upgrade its existing stock. That implies that NATO will start the new chapter with a significant edge.

The inclusion of Finland and Sweden will enhance NATO’s capabilities in two critical ways. One is simple geography. The Baltic Sea will no longer be a gray security zone, and Finland’s 1,340-kilometer border with Russia will no longer be a source of concern about a land invasion that could threaten NATO in the north. The combined outcome will be a degradation of the Russian security situation in the Nordic and Arctic regions.

Listen to our new podcast

Military strength

Secondly, both Nordic countries have a long track record of successful cooperation with NATO. They have NATO-compatible force structures, and both have been alternately designated as NATO’s “number one partner.” It speaks volumes that none of the existing members objected to their joining on military grounds.

Accepting that Finland and Sweden will add serious strength to the alliance, what does this, in turn, mean for the future posture of NATO’s northern flank?

The main asset of a new Nordic bloc is its combined air force. All told, the four Nordic members will be operating 239 top-of-the-line combat jets. Once contracted deliveries have been completed, Denmark, Norway and Finland will be flying 143 American F-35 fighters:

Facts & figures

- Denmark has purchased 27 of these formidable aircraft

- Norway is in the process of receiving 52 F-35s

- Finland recently opted to acquire 64 F-35s

- The Swedish Air Force boasts 96 Saab JAS Gripen fighters.

In recent years, the Finnish and Swedish air forces have been involved in numerous bilateral tactical exercises. They have ample experience of drills together with NATO aviation in the north of Sweden. The flyers will be supported by the advanced Swedish Erieye Airborne Early Warning and Control System and operate from airfields close to critical Russian infrastructure and base areas.

Shoring up defense

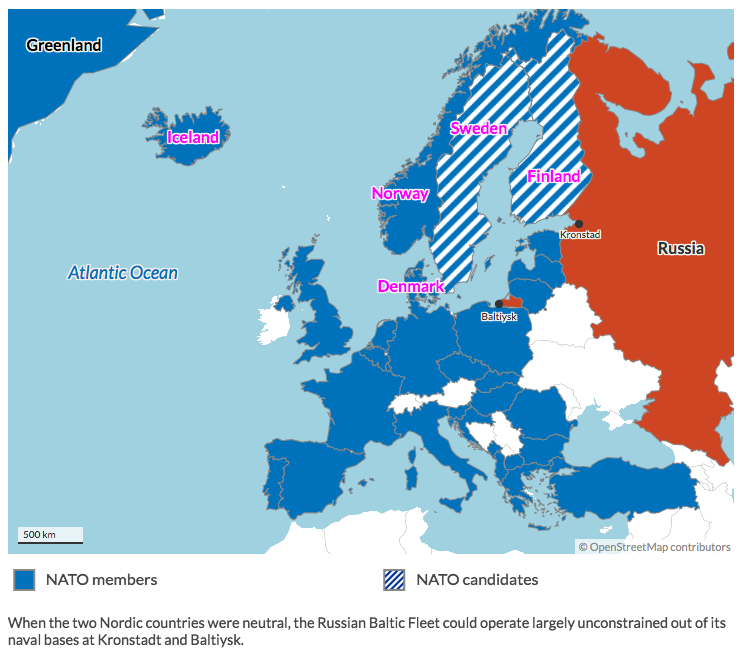

Including Finland and Sweden in NATO will also significantly alter the dynamics in the Baltic Sea area. When the two Nordic countries were neutral, the Russian Baltic Sea Fleet could operate largely unconstrained out of naval bases at Kronstadt, outside St. Petersburg, and at Baltiysk in the Kaliningrad exclave. Its main adversary would be smallish Polish, German and Danish naval assets.

Facts & figures

A big part of the Russian lock on the Baltic was the A2/AD (anti-access/area denial) “bubble” at Kaliningrad, which posed a formidable threat to NATO naval movements in the Baltic Sea. There was also a latent threat that a swift Russian airborne assault to capture the demilitarized Swedish island of Gotland, strategically located in the center of the Baltic, would have made that lock even more formidable.

Looking forward, the Baltic Sea will now, for all intents and purposes, become a NATO lake, where the Russian Baltic Fleet may operate when and how NATO allows it to do so. During a time of crisis, Russian assets would be bottled up.

Finland and Estonia are currently discussing the development of anti-ship missiles that would effectively throw a barrier across the Gulf of Finland. Given that the distance from Tallinn to Helsinki is only 87 kilometers, shore batteries on both sides would ensure that no Russian surface vessels from Kronstadt could pass into the Baltic without permission.

Read more on the Nordic states:

Nordic disunion

Finland: On top of the world, but for how long?

Then there are Swedish submarines. While Finland has not developed its submarines since World War II (first because of prohibitions in the 1947 Paris Peace Treaties, and then since 1990 by choice), the Swedish Navy has a long tradition of operating sophisticated subs in the tricky brackish waters of the Baltic Sea. In a crisis, they may be relied upon to undertake aggressive mining of the Russian ports at Kronstadt and Baltiysk and to lie in stealthy ambush for antiquated Russian subs trying to leave their bases.

In the southern Baltic, the Kaliningrad fortress will be countered by Danish missile defenses and air force assets on the island of Bornholm, by stealthy Swedish missile corvettes patrolling the approaches to Baltiysk, and by a determined Swedish buildup of assets on Gotland, ranging from Patriot missiles to mechanized ground forces and a naval base.

Containing Russia

Finally, Finland and Sweden will strengthen NATO with ground forces with considerable combat experience in mountainous Arctic territory. These forces have exercised with NATO units in war games like Cold Response. Together with Norway, they will present a powerful threat to Russia’s basing areas on the Kola Peninsula, home to its Northern Fleet and an important component of its nuclear forces.

The alliance’s Nordic expansion will transform the long border between Finland and Russia into a significant Russian vulnerability. In a crisis, Finland can mobilize 280,000 well-trained and motivated troops, supported by the most powerful artillery force in Europe. The crucial role played by artillery during the war in Ukraine has brought home that Finland was correct in ensuring that its arsenal includes 700 howitzers, 700 heavy mortars and 100 multiple rocket launchers. For Russia, such a force constitutes a powerful deterrent.

Scenarios

Russia’s military degradation

A baseline scenario for future developments will contain three components. The first departs from the ongoing degradation of Russian military capabilities. Intelligence gathering from the battlefields in Ukraine has provided stunning insights into the dependence of Russian arms producers on electronics from Western manufacturers. Import substitution will, at the very best, cover a small fraction of the future needs for such components, and authorities in the United States can be expected to pursue an aggressive policy of tracking down and sanctioning any intermediaries that attempt to help Russia evade the sanctions.

Nordic industrial strength

The Nordic countries’ considerable military-industrial capabilities give them a significant technological edge over the Russian opponent. Some big players have already made extensive contributions to Ukraine, and with markets booming, they may now be expected to invest heavily in research and development.

European NATO capabilities

The second component is improved force coordination. With Finland and Sweden inside NATO, it will be possible to formalize and extend the already established forms of cooperation. One possibility is that the Nordic bloc may assume full responsibility for the NATO Air Policing mission protecting the skies over the Baltic states.

Another is a joint Nordic command for the Arctic. Russia has invested heavily in a military presence in the region, building modern bases and setting up dedicated Arctic brigades. As much of Russia’s capacity has now been wasted in Ukraine, a joint Nordic Arctic command would allow the region’s NATO members to contain Russia without support from the U.S. and Britain.

Nordic bloc reach

A Nordic bloc’s third and most speculative component concerns collaborative foreign and security policy. After World War II, there were discussions on a Nordic defense union. However, as Denmark and Norway preferred to join NATO, while Finland and Sweden chose neutrality, that came to nothing. If the four could presently manage to resuscitate old plans on tighter cooperation – this time inside NATO – it could result in a formidable force.

The Nordic countries (including Iceland) have a combined population of just above 27 million and a combined gross domestic product of $1.37 trillion, making it the world’s 12th largest economy. A Nordic bloc could speak with a strong voice both inside NATO and in the broader community that will need to come together to support Ukraine’s reconstruction, for example. Above all, it could provide added resolve in dealing with a postwar Russia, sidelining German ambitions to negotiate a return to commercial relations.

Swedish weakness

The weak link in this scenario is Sweden. While Finland responded to the Russian aggression against Ukraine by reaching a speedy and near-complete political consensus on joining NATO, Sweden displayed mixed emotions about the alliance. Opinion polls still show a majority in favor of NATO, but society remains marked by powerful anti-NATO and anti-American sentiments that influence the political sphere.

When and if it is admitted, Sweden will be a recalcitrant member. A significant part of the country’s opinion clamors for the government to sign a ban on nuclear weapons, say “no” to U.S. forces stationing on Swedish soil and proclaim Sweden will not send troops to defend other NATO members. None of these will help show common resolve against Russia.

Nordic disunity

The outlook for Nordic military-industrial cooperation is also clouded by less than cordial relations between Sweden and its neighbors. The Swedish government had high hopes that Norway and Finland would opt for its Gripen fighter. This choice would have provided a substantial boost to Nordic military-industrial cooperation. But as both countries finally chose the U.S. F-35, there was much bad blood on the Swedish side. There is also a sour track record of failed cooperation between Sweden and Norway on building the Archer self-propelled howitzer and the joint procurement of new helicopters. Overcoming these obstacles will not be easy.

Considerable as these roadblocks may be, the most challenging task for a Nordic bloc would be to come together on foreign and security policy. The war in Ukraine has provided ample evidence on how Finland will be ready to join an alliance composed of the Baltic and Central European states (minus Hungary) that would include Denmark and Norway and be backed up by the U.S. and the United Kingdom.

The final takeaway

Sweden has, in contrast, shown that it will side with Germany in procrastinating and seizing every opportunity to promote negotiations with Russia. Like Germany, Sweden features a large pacifist community, a strong presence of Russia’s sympathizers in the public sphere and a downgraded national defense. These security factors cast doubt on whether it will be able to simultaneously help Ukraine and embark on rebuilding its armed forces.

While a coherent Nordic bloc could make a significant difference to internal NATO relations and its future relations with Russia, the likelihood of this scenario emerging is not exceedingly high. The Kremlin will still be able to count on exploiting persistent weak spots.