Norway’s oil fund braces for climate challenges

Norway’s sovereign wealth fund has had a good run. But will it be able to stand up to the social and political challenges posed by climate change?

In a nutshell

- Norway’s oil fund has benefited from sound management

- Green activism puts the fund’s future in question

- Politicization could endanger innovation-based environmental progress

Norway is everything that an oil-rich nation should not be. According to the conventional wisdom, countries with a dominant energy sector should be in big trouble, plagued by authoritarian rule, rent-seeking and rampant corruption. There is plenty of evidence to back this claim – from Russia to Nigeria and Venezuela, not to mention across the Arab world. Even a stable democracy like the Netherlands gave us the term “Dutch Disease,” allegedly contracted from the 1959 discovery of a large gas field in the North Sea.

The common thread running through all these narratives is the “resource curse,” a counterintuitive notion that suggests a cruel irony: the apparent blessing of natural resources can end up harming a society. But even though Norway is simply awash in oil and gas, it resolutely defies any hint of having been cursed by this wealth. Its democracy is robust. It routinely ranks among the least corrupt nations in the world. And it has not fallen ill with even the slightest symptoms of Dutch Disease.

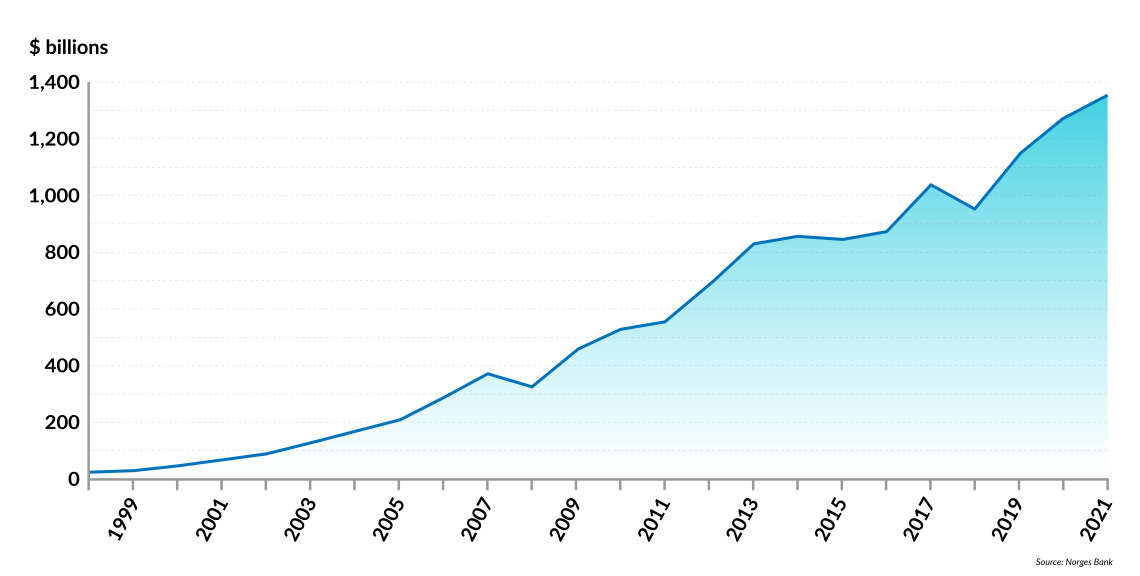

In contrast to the common story, Norway’s discovery of giant offshore deposits of oil and gas has been a tremendous blessing, enriching the population beyond belief. With assets that have risen to $1.4 trillion, the Government Pension Fund Global is today the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund, ahead of China Investment Corporation. Its assets are four times the country’s gross domestic product (GDP), and it holds 1.4 percent of all shares around the globe. Not bad for a country with a population of just over 5 million (just 0.06 percent of the total). A solid track record of democratic accountability and adherence to the rule of law also ensures that citizens need not fear evil oligarchs will abscond with their wealth. In short, Norway’s handling of its vast natural resources can only be viewed as a tremendous success story.

Activism threat

Or at least that was the case before the message on climate change began to strike home. Today the outlook is marred by a novel threat, which may prove a tougher challenge than fiscal prudence. The managers of the oil fund, and ultimately the government, are now squarely in the sights of climate change activists, who are demanding fundamental changes in how the fund operates.

There is a great deal at stake. One issue is how the wealth will be managed as questions are raised about whether a fund created by hydrocarbon revenue can be a responsible investor. Another question is what will happen if the economy is forced to rapidly scale back extraction. In the end, political stability may even be at stake if conflict over these emotionally charged matters spills over into domestic politics.

Norway’s gas exports to the EU have been on par with Russia’s, but with none of the conflict.

Ever since Norway made its first hydrocarbon discoveries some 50 years ago, its role as a major oil and gas producer has been associated with the development of cutting-edge offshore drilling technology. Although its energy industry has not been alone in this, it has faced a far more daunting challenge than most others: drilling at great depths, under Arctic conditions of very low temperatures and very high winds. Its track record has been excellent.

Oil and gas have also been viewed as commercial rather than political assets. Norway’s gas exports to the European Union have been on par with Russia’s – but with none of the conflict that has surrounded the latter. When Norway proposes building a pipeline, hardly anyone notices. When Russia does the same thing, it is an international controversy.

When the party ends

The main question concerns how long this happy state of affairs will last. Given that hydrocarbon wealth is a declining resource, there will inevitably come a day when the party ends. The growing importance of climate change activism suggests that this day may now come sooner than previously expected.

As fields in more accessible waters have peaked, the hunt for new resources has been moved north. Like Russia, Norway has been eyeing presumably huge new deposits in the Arctic, where engineering challenges are compounded by claims that drilling will damage highly sensitive ecosystems.

Domestic activists recently sought to block this move with legal action, alleging that prospecting violates people’s constitutional rights to a healthy environment. That case was taken all the way to the Supreme Court, where it was defeated. If renewed challenges prove more successful, the outcome for the industry could be grave.

Facts & figures

Norway’s sovereign wealth fund – market value

The petroleum sector accounts for about 14 percent of Norwegian GDP and about 40 percent of exports. Although the economy is robust enough to weather even a radical downsizing, there would be severe regional consequences. The oil and gas industry is clustered around the city of Stavanger, in the southwest of the country. When oil was first discovered, this was a struggling fishing community. It then rose to become one of the country’s wealthiest towns. But after the global economic crisis in 2008-2009, when the oil price plummeted, it suffered unemployment and a depressed housing market. That could happen again.

Well-managed wealth

The main reason Norway can still look with confidence even at some of the gloomier scenarios is that it has such a solid record of managing its resource wealth.

The first discovery of oil in the North Sea was made in 1969. Named Ekofisk, it was the largest offshore deposit ever found, and it immediately raised the challenge of how to manage the wealth. If politicians had gone on a spending spree, the country might well have ended up suffering all the problems of the resource curse. Infighting between interests for access to the oil wealth could have fueled the rise of populist parties, endangering political stability. And the economy would have been sure to catch a bad case of Dutch Disease, which involves an inflow of dollars that damages the non-resource sector in two ways. First, it causes appreciation of the local currency, which boosts imports and penalizes non-resource exporters. The other result is that the resource sector gets the upper hand in competition for everything from labor to investable funds.

The fund is guided by rules designed to prevent the domestic economy from overheating.

In Norway, on the other hand, lengthy deliberation led to a political consensus that the wealth must be placed out of reach. In 1990, legislation was passed to set up the pension fund to manage the surplus generated by the state-owned oil and gas companies.

The fund is guided by two key rules, designed to prevent the domestic economy from overheating. One is that investments can only be made outside Norway, and the other is that the government may only spend a certain amount of the fund’s value during a specific year. At the moment that limit is 3 percent. That may sound like a trifle, but considering the sheer size of the fund, it still accounts for about a fifth of government spending.

Temptations to spend

Challenges to this arrangement have arisen over the years, as temptations emerged to cure social ills by dipping into the fund, but the fortress has held. The danger today is that aggressive activism may force a massive boost in spending on green transformation. Avoiding this will require a delicate balancing game.

Norway’s official reaction to climate change has been cautious, weighing adherence to internationally agreed emission targets against measures to safeguard the interests of its oil and gas industry. Following its accession to power in October last year, the Labor-led coalition government of Jonas Gahr Store announced it would commit to the European Union’s target of reducing net emissions by 55 percent by 2030. But it also noted that the path to green energy would be gradual, saying the industry would be “developed, not dismantled.”

The oil fund has responded to increasing pressure to use its clout for other causes, but progress has been gradual. In 2019 the fund was instructed to divest from companies that only explore for oil and gas, but to keep its stakes in those that also have renewable energy divisions. In 2021 it divested from 43 companies that it considered “not to have sustainable business models,” and a new assessment method was introduced to prevent unsuitable investments.

Political tool

In November 2021 Pension Fund CEO Nicolai Tangen told the BBC it would not divest the billions of dollars it had invested in oil and gas companies, because this would not help solve the problem of transitioning to greener energy. In his words, it would be “much more powerful to be an active owner and have a constructive dialogue with these companies.”

The days when the oil fund could remain aloof and apolitical have now clearly ended.

The essence of the Norwegian approach was captured in a statement last spring by then-Prime Minister Erna Solberg. Noting that the petroleum industry had been one of the main engines of Norway’s economic growth for more than 50 years, she emphasized that “If we lose the growth potential of this industry, we will also lose much of the momentum in Norway’s transformation.”

The days when the oil fund could remain aloof and apolitical have now clearly ended. In late 2019, well before becoming prime minister, Mr. Store noted that “we have to get used to saying that the oil fund is a political tool.” While environmental activists were encouraged, representatives of the center-right government and of the central bank were aghast.

Scenarios

The dilemma facing the government is whether Norway will use its hydrocarbon-generated wealth to drive a green agenda based on hi-tech engineering solutions, or whether it will be captured by green activism aimed mainly at changes in people’s behavior. While the first scenario would be compatible with maintaining fiscal prudence, the second would carry a distinct risk of lavish spending.

There can be no doubt that Norway has both the engineering skills and the capital resources to pursue an agenda of green transformation built on innovation. It already has the world’s highest per-capita use of electric cars, with 42.4 percent of autos sold in 2019 being electric. In April 2021, the oil fund also announced its first investment in unlisted renewable energy infrastructure, with an agreement to buy 50 percent of the Borssele 1 & 2 offshore wind farm in the Netherlands.

The approach that has been laid out by the Store government has won broad approval. In the words of lobby group Norwegian Oil and Gas, the plan will “ensure continued development and value creation from oil and gas, but also … finance a green transition.”

Yet it has also faced scathing critique from environmentalists who seek a different path. In the words of Karoline Andaur of the Norwegian World Wildlife Fund, the measures do not go far enough and are “horrifying in terms of the still high activity in oil and gas.”

The extreme alternative to a green transformation led by oil fund initiatives and investments would be a wholesale dismantling of the Norwegian petroleum sector and a rapid sale – presumably at a great loss – of billions of dollars in hydrocarbon-related shares. The specter of this scenario will likely be enough to keep the mainstream political parties committed to their current gradual approach.