Oil market outlook: Expectations and realities

Since about June, oil prices have remained remarkably stable. Still, plenty of uncertainty remains about when consumption might recover and what the long-term future holds for the world’s energy giants. As a result, oil companies’ shares have declined steadily.

In a nutshell

- Some analysts expect a sharp rise in oil prices next year

- Investors, however, have a grim outlook for oil companies

- A focus on renewables has not changed the negative prospects

This report is the fourth installment in a monthly series on the latest developments in oil markets by GIS Expert Dr. Carole Nakhle.

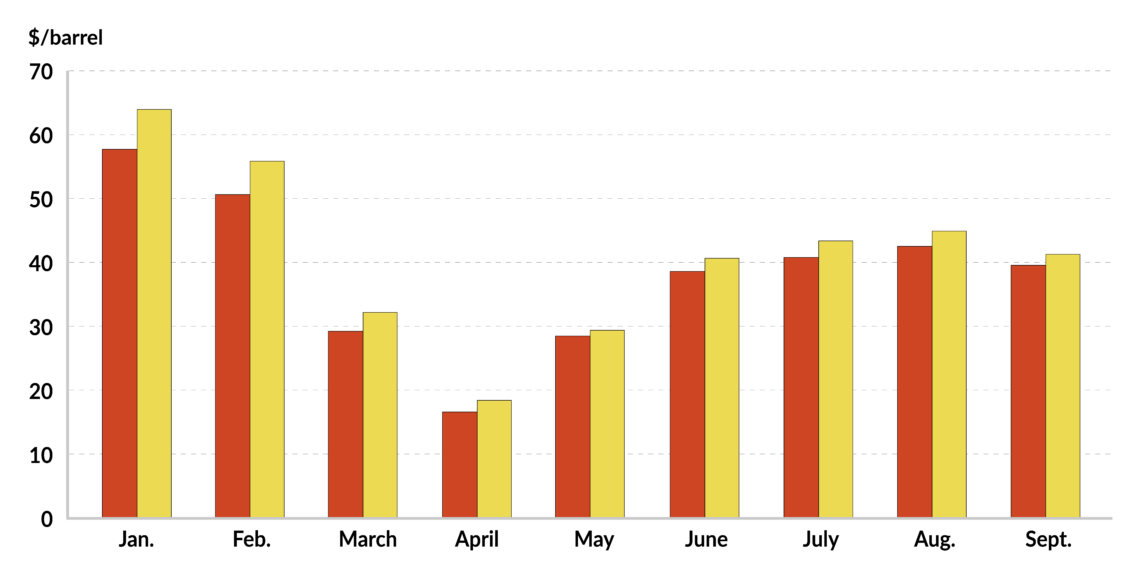

Oil prices and their markets remain impressively stable despite enormous uncertainty around how the Covid-19 pandemic will develop and how fast the global economy (and therefore oil demand) will recover. A lot of the credit goes to OPEC+. The group – consisting of OPEC, Russia and several other oil-producing countries – has not managed to bring prices back to their pre-Covid levels, but it has succeeded in stabilizing them in the range of $40-45 (for Brent crude).

The slight increase in oil prices in August brought some optimism, leading commentators to predict a tightening market – and therefore much higher prices – by the end of the year. Such predictions soon proved premature, as oil prices fell back to their June levels, where they seem to have settled for now.

Energy analysts may be overlooking some forces that could discredit their analyses.

Nevertheless, most forecasting agencies expect prices to rise next year. Banks like Goldman Sachs are the most bullish, predicting that prices will hit $65 per barrel by the third quarter. Those expectations are in line with most economic forecasts, which predict rapid growth starting in 2021, though a return to pre-Covid levels is not expected for a few years.

Only time will tell how accurate such projections are. Energy analysts are no strangers to changing forecasts. This time they may be overlooking some brewing forces that could discredit their analyses. The oil companies’ recent share price performance shows the disconnect between energy analysts’ expectations and those of investors.

Facts & figures

Oil market indicators

- In its October World Economic Outlook, the International Monetary Fund projects global growth of 5.2 percent for 2021, 0.2 percentage points below its June projection

- Oil prices slipped below $40 a barrel in early October, their lowest level since June

- OPEC+ is due to increase production slowly in the coming months as per its April 2020 deal

- The International Energy Agency warned of “limited headroom” to absorb additional supplies amid oil demand uncertainty

Competing visions

Despite the prevailing market stability since June, there is no shortage of commotion around oil markets. Analysts concerned with short-term market movements closely track daily and weekly changes in production, demand and inventories. A small reduction in the latter brings talk of a rally in prices, only for the excitement to dissipate the following week as inventories build up again.

Others prefer to focus on the longer-term picture. Oil companies, international organizations and OPEC have published one outlook after another, with competing forecasts for oil markets’ path over the next 20 to 30 years. They have all engaged in guesswork about when oil demand will peak. Oil companies like BP have predicted it will come sooner rather than later, as they try to rebrand themselves as energy – not oil and gas – companies that are readily embracing the green transition.

Meanwhile, those who want to see the demise of the oil and gas sector trumpet oil companies’ shrinking market capitalization, as well as the rising valuation of green businesses. The most notable such development was when ExxonMobil was dropped from the Dow Jones Industrial Average index and was overtaken in market capitalization by NextEra Energy, a company specializing in renewable energy.

Facts & figures

Stock prices

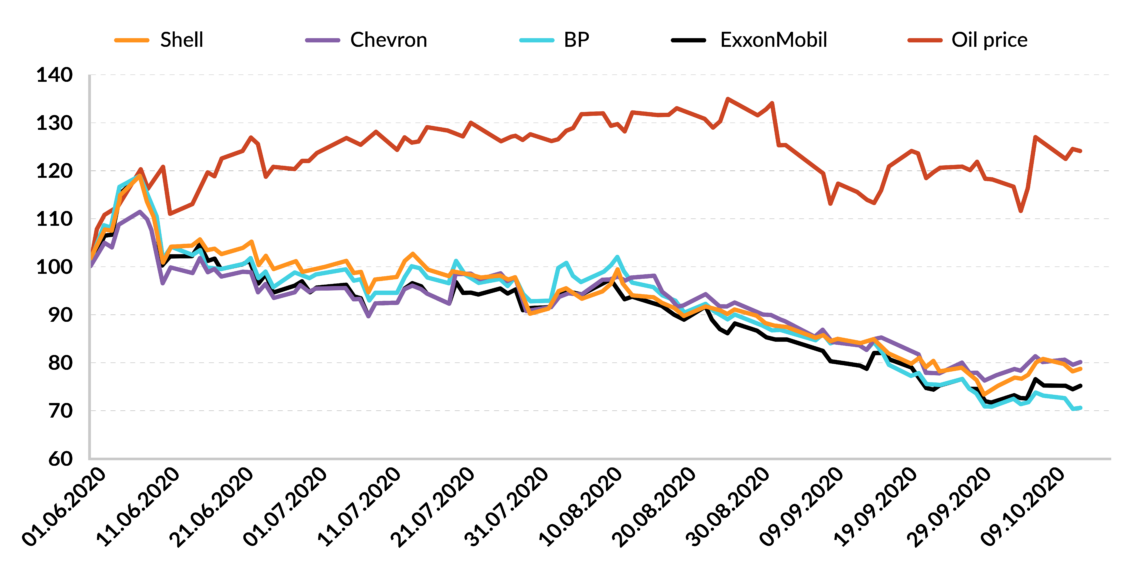

Many commentators have argued that the decline in oil companies’ stock prices is a clear indicator that the oil age is finally reaching its end. Yet it is difficult to believe that investors have suddenly fallen out of love with the oil companies.

Of course, the increasing popularity of clean energy plays a role, as does investment funds committing to cutting fossil fuel stocks from their portfolios. The question is how big those roles are. Typically, investors would rather hunt for good returns than stand on moral principle.

In the short term, the value of international oil companies is a good proxy for oil price expectations. The recovery in prices after their darkest phase in April this year was not matched by an increase in these companies’ share prices, probably indicating that the wider business and investor community disagrees with the energy community. Markets are not convinced that oil prices will rise significantly anytime soon.

To diversify successfully, companies need to find areas where they would perform better than the incumbents.

Industry leaders like BP CEO Bernard Looney have argued that oil companies’ recent share price performance is exactly why these firms need to shift focus, concentrating more on green energy and less on hydrocarbons. Interestingly, the stock prices of companies that are more committed to the energy transition – typically European majors – have not behaved differently from those of firms that maintain their dedication to their conventional business, primarily the oil giants based in the United States.

Apart from the price risk, the real danger for oil companies may come from within. To diversify successfully, companies need to find areas where they would perform better than the incumbents. There is no reason to believe that oil companies would perform better than existing clean energy providers when it comes to building solar power plants or wind turbines.

Back in the 1970s and 1980s, the oil majors tried to diversify into mining – an industry that probably shares more similarities with oil and gas than renewable energy. Some even ventured into the nutrition business (BP) and others into office supplies, including producing typewriters (Exxon). Within a decade, they had divested out of these failed ventures.

Unfavorable prospects

There are good reasons for stock market investors to be skeptical of predictions for a steep increase in oil prices next year. Chief among them is the health of the world economy. While the pandemic plays a key role in determining how fast global growth bounces back, the longer economic activity is held in check, the greater the risk of additional structural damage that could hinder recovery.

For example, the longer the crisis takes, the more unemployment will spread to sectors that had not been hit as hard by the pandemic. The loss of jobs and businesses would further depress economic performance, oil demand and prices.

An additional risk is that OPEC+ may well come under significant pressure. The more successful it is at shoring up prices, the higher the chance that additional supply from the U.S. and elsewhere will come into the market.

A second, much less discussed reason to be skeptical about oil prices rising is the record spare capacity that OPEC+ has built up because of its historic production cuts. If oil demand does not pick up as expected, this capacity will not be absorbed next year, as many analysts currently expect. In that case, OPEC+ will find it difficult to stop its members from breaking their commitments to cut production.

All these factors tell investors that oil prices should remain more stable than what energy analysts anticipate – which explains the poor performance of oil companies’ shares.

To withdraw investment from oil and gas companies because one expects them to be less profitable in the future is different from withdrawing investment because they are complicit in climate change. In the first case, investors simply follow the money. In the second, they are making an ethical statement. We are likely seeing the first case playing itself out in the market today.