The U.S.-China trade war may return

The Phase One trade agreement between the U.S. and China, signed in January shortly before the coronavirus pandemic, ended two years of a disruptive “trade war” between the two countries. As anti-China sentiment in the U.S. grows, the deal may prove short-lived.

In a nutshell

- U.S. frustration over China’s policies is growing

- In this election year, calls for “making China pay” are louder

- Phase One of a trade agreement between the two conflicting powers might get scrapped instead of leading to Phase Two

The United States’ annoyance toward China registered long before the coronavirus pandemic and the rise of controversies related to Beijing’s policies during the crisis. The administration of President Donald Trump and members of Congress have been bitingly critical of China’s business activity inside and outside the U.S. However, these negative attitudes have sharpened dramatically since the outbreak of COVID-19 and the resulting human and economic tragedies.

In the midst of all this lies Phase One of the Economic and Trade Agreement between the U.S. and China, known as the Phase One trade agreement. The deal, signed in January 2020 less than two weeks before China began shutting down because of the new virus, marked the end of two years of a U.S.-China “trade war” which saw heated rhetoric and an escalation of tariffs on traded goods.

It seems as though every week there is a new proposal coming out of Washington to ‘make China pay’.

The life expectancy of the Phase One deal is now in question, as lawmakers in Washington increasingly demand punishing China for its role in the outbreak. This sentiment puts President Trump in the awkward position of simultaneously trying to protect his signature trade deal and to demonstrate toughness on China in an election year.

U.S. frustration

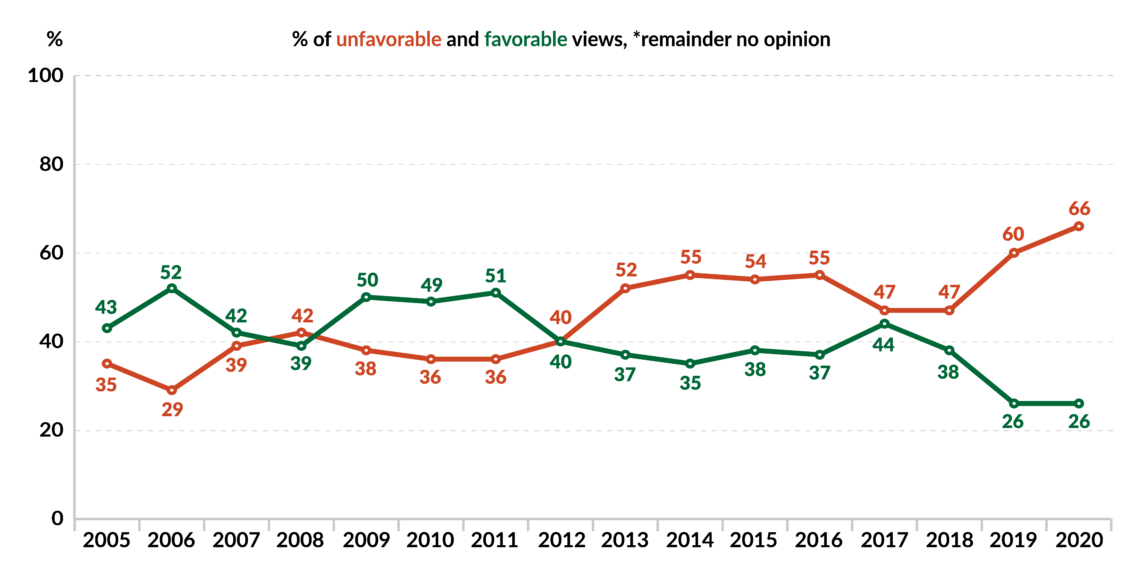

According to Pew Research Center, 66 percent of Americans now hold an unfavorable view of China – the highest percentage in the last 15 years. The sentiment is most negative among those who are older and Republican-leaning.

Longtime critics of Beijing in the administration have found a new voice as they criticize the role of China’s central government in suppressing information about the virus, which led to its spread. Beijing was also putting about disinformation about the origins of the virus, suggesting that it could have been planted in China by U.S. military personnel.

The frustration over Beijing’s reported role in allowing the pandemic to develop has sparked a frenzy of wild conspiracy theories. Also, it has led some policymakers to take a second look at U.S.-China relations in other areas – including the U.S.-China trade relationship.

Calls for action

Now, it seems as though every week there is a new proposal coming out of Washington to “make China pay” for its role in the global drama. The phenomenon is hardly surprising, given that this is an election year and many lawmakers have been stuck at home listening to their frustrated constituents. The U.S.-China trade war may be over, but the odds are high that new areas of conflict will be added to the existing ones over the next year.

Some of the “make China pay” proposals – like refusing to service the U.S. Treasury securities owned by Chinese investors or ignoring the interest on this debt – could be outright dangerous for long-term U.S. financial interests. The policy could devastate faith in the American credit system and enforcing such measures is practically impossible given the openness of bond markets. According to Director of the National Economic Council Larry Kudlow, the White House had no intention in pursuing such ideas.

Some lawmakers want to see action taken against Chinese investment in the U.S. One proposal would seek to block all new Chinese investment. However, the U.S. has in place a robust investment screening process that was updated just two years ago. It has the flexibility to deal with any malicious investments from China, specifically those pursued by its state-owned, politically controlled enterprises.

Policymakers’ biggest concern has been over the security of U.S. supply chains, especially those for pharmaceuticals and medical equipment. Some call flat-out for sourcing these goods from anywhere but China. One proposal has been that the administration needs to apply the “Buy American” policy for acquisition of such products as a way to incentivize the creation of a domestic supply chain. However, these preferential rules hardly ever achieve their intended goal.

China is off track on the import quota, but other elements of the deal have been implemented to the delight of U.S. officials.

The increasingly negative sentiment toward China has also given a boost to older “get tough” policies on China that are not related to the pandemic. These include criticism of China’s sway in Hollywood and its oversized influence in international organizations such as the United Nations, World Health Organization, World Trade Organization and International Telecommunication Union. China’s strategy of financing development in emerging markets through its Belt and Road Initiative is also coming under more intense scrutiny.

Will Phase One survive?

The U.S.-China trade pact could also be short-lived if it becomes more politically expedient for President Trump to punish China (and tax its exports to the U.S.) than to shield the deal.

Facts & figures

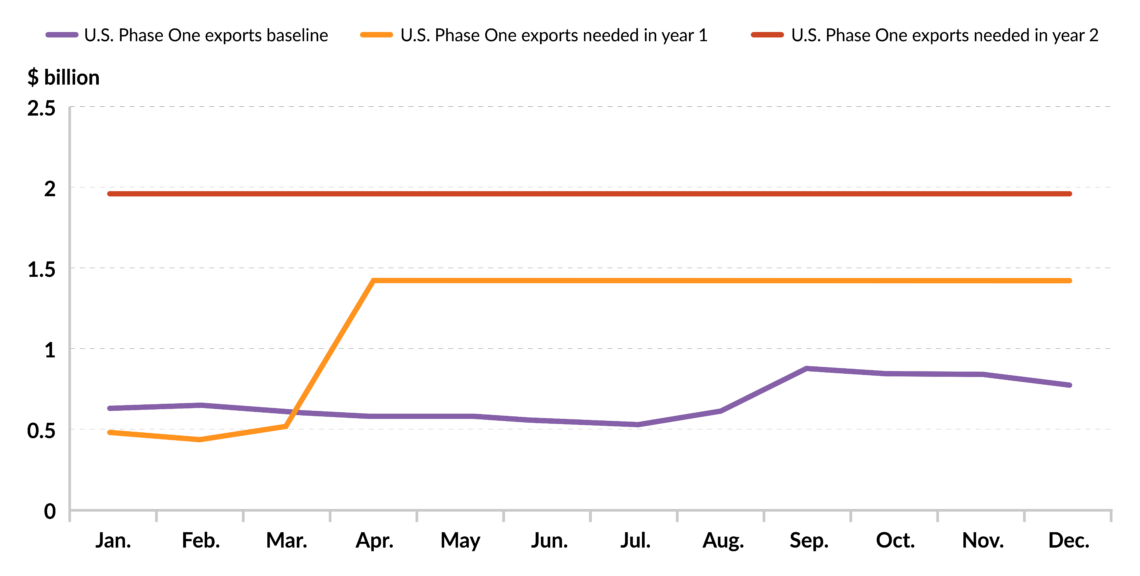

Already, there is a growing question over China’s ability to honor its obligation to make $200 billion worth of additional purchases in the U.S. over two years. Most trade analysts doubted China would be able to make good on that promise – and indeed, it seems unlikely Beijing could fulfill it now, during a global recession.

In the first three months of 2020, China has only been able to make $14.4 billion worth of Phase One purchases. It would have to nearly double its monthly buying to meet the $142.6 billion year-one import goal established under the agreement.

Despite China being off track on this particular commitment, other elements of the deal, including those that necessitate internal changes in China, have been implemented to the delight of U.S. officials. The Office of the U.S. Trade Representative and U.S. Department of Agriculture so far issued three statements detailing the progress made in implementing the deal. These reforms would be hard to reverse if the Phase One deal falls apart.

Changes to watch for

In the constant flow of China-related policy proposals in Washington, a handful stick out. Whether the administration acts on them, however, may depend on when the U.S. economy starts to reopen and on the proximity to the November election.

The first and second most likely candidates for implementation are the proposals aimed at shifting supply chains of pharmaceuticals (particularly active pharmaceutical ingredients or API) and personal protective equipment (PPE) out of China.

The idea of the White House issuing a “Buy American” rule for these goods has already been floated around Washington. Such a policy would require federal agencies to only source these goods from U.S.-based suppliers. Given the high demand for medical goods during the pandemic, it would not be surprising to see the administration also consider using the authority of Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 to tax the imports of these goods as well, to encourage domestic production. Either of these policies would increase the supplies’ cost and would be unpopular as long as the pandemic continues.

Washington’s move to increase tariffs on imports from China would cause the Phase One deal to fall apart.

Along with API and PPE supply chains, there is a drive to shift other manufacturing out of China. Washington analysts have taken note of Japan’s recent efforts to bring its manufacturing operations out of China. The government of Japan recently allocated $2.2 billion to help companies with their moving costs. There may be an effort to subsidize the homebound U.S. firms as well, but this could meet opposition from fiscal hawks concerned with a ballooning U.S. federal deficit.

Finally, there are efforts to calculate the amount of restitution China supposedly owes the U.S. for its negligence leading to the spread of the virus. Any possibility for the U.S. to make a legitimate claim for a specific amount could be used for punitive action against China. The most likely form of action is more tariffs on imported goods. A move to increase tariffs on imports from China would cause the Phase One deal to fall apart. Also, it could risk retaliation from China.

Scenarios

As pressure builds in the U.S. to take more action against Beijing, the Trump administration and Congress may use China’s apparent inability to meet the import requirements of the Phase One deal as an excuse to scrap it and slam new rounds of tariffs on imports from the rival economy. From the Trump administration’s perspective, any deal with China can be renegotiated in a second term in office.

While the administration is actively looking at ways to restructure API and PPE supply chains out of China, it is unlikely to engage in projects that may be too disruptive during the COVID-19 pandemic. Dealing with the economic costs of containing its spread remains the U.S. officials’ primary concern.

However, if Washington begins to look in earnest for new ways to punish China, the U.S.-China Phase One deal may be the first to go.