The end of the Portuguese exception

Commentators have hailed the politics of Portugal as an “exception” in Europe. In Lisbon, a socialist party presides over a healthy economy while far-right and populist-right parties lack significant support. The pandemic, however, is challenging that status quo.

In a nutshell

- Portugal's "socialist success story" may be coming to an end

- Lockdown measures have had a severe impact on the country's economy

- In response, right-wing political parties are gaining momentum

In recent years, some analysts have described Portugal as Europe’s “socialist success story”: a winning model that could serve as an antidote for populism. Now, however, the end of the “Portuguese exception” may be in sight. The devastating effects of the Covid-19 pandemic are laying bare the fragility of the Socialist-led government, while a party on the radical right is gaining momentum. Portugal’s economic and political outlook could be in for a change.

Fragile ‘success’

The Portuguese Socialist Party led the government from 2015 to 2019 under an agreement (known as the “contraption”) established with the radical Left Bloc, the Portuguese Communist Party and the Ecologist Party “the Greens.” In 2019, the Socialists won 36 percent of the vote, increased their representation in parliament by 20 seats and, unlike in 2015, gained the most votes of any party. Antonio Costa was reappointed prime minister, this time with more leverage over his partners on the left (though their support remained necessary to approve critical legislation, including the government budget).

The 2015 and 2019 governments’ records are mixed. As it came to power, the “contraption” benefited from the momentum generated by the center-right government of Prime Minister Pedro Passos Coelho, who ushered the country out of an economic crisis. After taking over, the Socialists managed to continue lowering the ratio of debt to gross domestic product (GDP) and reducing the unemployment rate.

Pressured by its partners on the left, the government focused on increasing incomes for the most vulnerable groups, raising the minimum wage and welfare benefits. While such measures brought short-term political gains, they did not address the economy’s structural problems. If measured by purchasing power parity, the average per capita income in Portugal is the same as in the 10 countries that joined the EU in 2004 – this almost three decades after Portugal joined the European Economic Community.

Overall public investment under Prime Minister Costa has been less than during the ‘troika’ years.

An important element of the socialist strategy to balance public accounts while working to secure reelection has been to decrease public investment in areas where cuts are less visible and their effects more diffuse. Overall public investment under Prime Minister Costa’s leadership has been less than during the years when the “troika” of the European Commission, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund insisted on austerity. Public expenditure in the National Health Service during the 2017-2019 period, for example, was 6.1 percent below that of the 2012-2015 period. Lower levels of public investment were accompanied by a tax burden that reached historical highs (35 percent of GDP), and is above the OECD average.

Not surprisingly, Prime Minister Costa has been accused by the radical left of not being “socialist enough” (for example he did not completely reverse the labor reforms implemented under Prime Minister Passos Coelho). Some in the center and on the right accuse him of perpetuating a vicious cycle of high taxes, government inefficiency and economic stagnation. In the Heritage Foundation 2021 Index of Economic Freedom, Portugal ranks 52 out of 169 countries. The country receives poor marks for its tax burden (60/100), government spending (42.4) and labor freedom (44.1).

Worst of both worlds

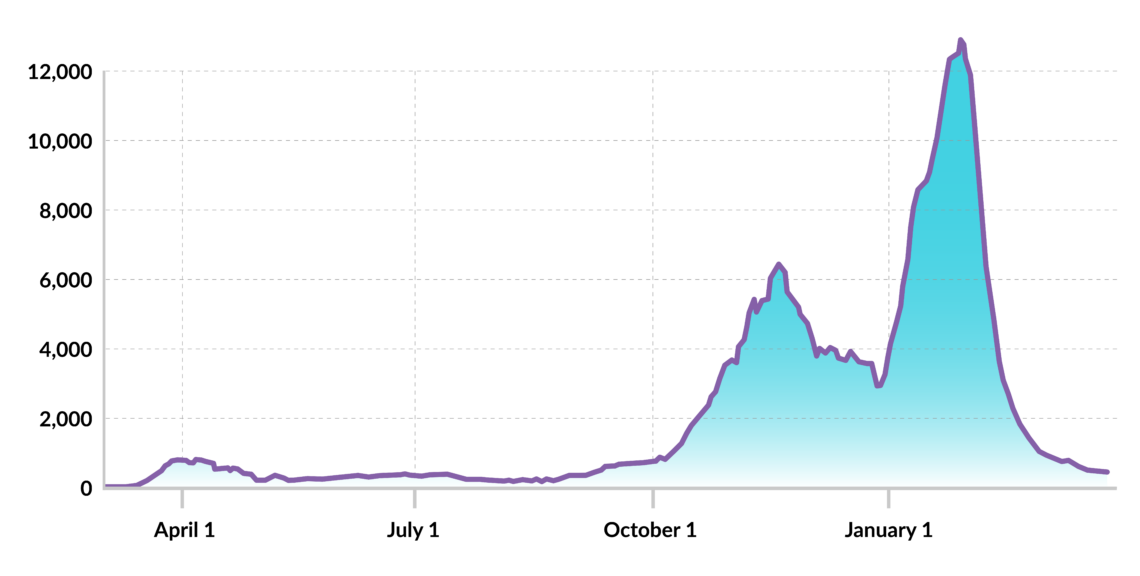

After overcoming the first wave of the pandemic with relative success, Portugal was severely hit by a second wave in January 2021, when it became the worst-affected country in Europe in terms of the death and case rates. With the health system on the verge of collapse, another strict lockdown was imposed.

Besides the dramatic impact on people’s health, this second wave and the measures adopted to contain it represented a crushing blow for an already fragile economy. The tourism sector, which typically comprises about 15 percent of economic activity (foreign tourism accounts for 8 percent of the country’s GDP) and had been a key driver of economic growth, was particularly hard hit. Profits in the restaurant and accommodation industries, for example, have dropped by 30 and 90 percent, respectively.

Facts & figures

Not surprisingly, unemployment has risen more dramatically in regions that are highly dependent on tourism, like the Algarve, Madeira and Lisbon. However, the lockdown has also had deep social implications. Some 30 percent of Portuguese students access meals and education material through social programs at their schools, which have been closed as part of the lockdown.

In 2020, GDP contracted by 7.7 percent – less than expected, but still severe. Exports slumped by 18.6 percent and private consumption fell by 5.6 percent. Considering the stringency and length of the lockdown, the outlook for 2021 is not encouraging.

Several measures have mitigated the economic and social effects of the lockdown, including a simplified layoff scheme available to businesses that had to halt or reduce their activities. Such firms account for around 20 percent of Portugal’s jobs. Another move that threw a lifeline to individuals and companies (and may mask the real economic effects of the lockdowns), was the implementation of a moratorium on loan repayments. Portuguese banks reported 25 percent of their loans were subject to the measure. According to Fitch Ratings, such loans total nearly 50 billion euros.

Recovery plan

The government has recently presented its plan for how Portugal will spend the 13.9 billion euros of EU recovery funding and 2.7 billion euros in loans that it is due to receive from 2021 to 2026. This European “bazooka,” in the words of the prime minister, will allow for the implementation of major structural reforms through three main pillars of action: resilience, climate transition and digital transition. Critics have pointed out several weaknesses in the plan. First, it is focused on public investment, with the state as the main agent of economic recovery. Portuguese companies will receive less than a third of the funding in subsidies. That probably will not be enough to help most of the country’s small and medium-sized enterprises, which make up about 99 percent of firms. Some 96 percent of these companies are microenterprises.

The plan to spend EU funding is focused on public investment, with the state as the main agent of economic recovery.

Strategies to support the recovery and growth in key economic sectors like agriculture or tourism are mostly absent. Under the “digital transition” pillar, for example, more than half of the available funds are destined for public administration. The plan also lacks clear targets and evaluation criteria. There are fears that some of the funds may be lost to inefficiency or corruption, and that key administrative positions overseeing the distribution of money could be politicized.

Changing political winds

As Portugal faces its biggest economic challenge since 1976, important changes in the country’s political configuration are appearing. The left has dominated Portuguese politics since the end of the authoritarian regime of Antonio Salazar. While the country’s Communist Party has remained one of the few of its kind to survive in Europe, new parties on the radical left have emerged. Groups on the right side of the political spectrum have tended to gravitate toward the center. Until recently, many considered Portugal a European “exception,” since radical right and populist elements did not have political representation.

In 2019, however, two new parties entered the Portuguese parliament: the Liberal Initiative wants less state intervention in social and economic matters, while Chega (“Enough”) is a right-wing party with a liberal economic agenda and a conservative approach to social issues.

Chega’s leader, Andre Ventura, has gained enormous visibility, not least for his controversial statements about the Roma community. While Chega has garnered the support of right-wing voters who traditionally cast their ballots for the center-right CDS and the main opposition Social Democratic Party, its main growth potential lies with those who do not usually vote. Turnout in Portugal has been declining for decades. In the 2019 parliamentary elections, 51 percent of the electorate did not vote.

Following the strategy implemented by other parties on the right and the radical right, Chega has captured media attention (if often negative) and has pursued an effective social media strategy. It also benefits from the general perception that the opposition is weak. In the January presidential elections, Mr. Ventura won 12 percent of the vote.

Scenarios

In the short term, the most important factor for Portugal’s outlook will be how the pandemic develops. Yet the country’s strategy to address the economic crisis and changes in its political scene will determine the medium- to long-term scenarios. Two broad eventualities are worth considering.

Business as usual

Under this slightly more likely scenario, reopening leads to a modest economic rebound in the second quarter of 2021 but does not offset the lockdown’s negative impact. It does, however, help avoid widespread social discontent. This will reduce the likelihood of a political crisis in the fall, when the parliament is due to approve the government budget for 2022. In the absence of a political crisis, and if key sectors like tourism and services gradually recover, the socialist government will make it to the end of the current legislative term.

Since it will ultimately control where the EU recovery funding flows, the Socialist Party will probably gain influence and reinforce its position within constituencies like the civil service. The number of people on the state payroll has ballooned in recent years, and now reaches more than 700,000. Though the details of its plan may change, the overall spirit – that the state should drive the recovery – will not. As a result, competitiveness could suffer, as could Portugal’s ability to attract much-needed foreign investment. The country’s economy will continue to stagnate for years.

Political crisis

Under this scenario, restrictions aimed at containing the pandemic last longer than expected – beyond the summer of 2021. On the other hand, families and businesses would also suffer due to the lifting of economic measures meant to ease the pain of the lockdown – like the loan payback moratorium. Social discontent would rise, and the parties to the left of the political spectrum would do poorly in the October 2021 municipal elections, provoking a political crisis. Wanting to disassociate themselves from the Socialist Party, the parties further to the left would increase their opposition to government proposals, including the budget, forcing early elections.

Two sub-scenarios could follow from this set of events. In the first, the Socialists retain power, either by securing a majority or by forming a coalition with other parties on the left. The Socialist Party would consolidate its position. Under the second sub-scenario, the parties in the center, center-right and right of the political spectrum would form a parliamentary majority. However, coming to a coalition agreement would likely be a rocky process, given that the Liberal Initiative has declared that it would not enter a national government with Chega.

If such a government could be formed, there would likely be substantial policy changes, since all four parties favor a less statist approach to the economy.