Intrigue and betrayal: Malaysia’s power struggle

According to a power-sharing agreement drawn up ahead of the 2018 elections, the Prime Minister of Malaysia was to resign mid-term. Before that could happen, a coup led to the collapse of the ruling coalition and the crowning of a new prime minister.

In a nutshell

- Malaysia’s leader has resigned amid a murky power play

- Many believe the new head of government lacks legitimacy

- The dislodged prime minister could make a comeback

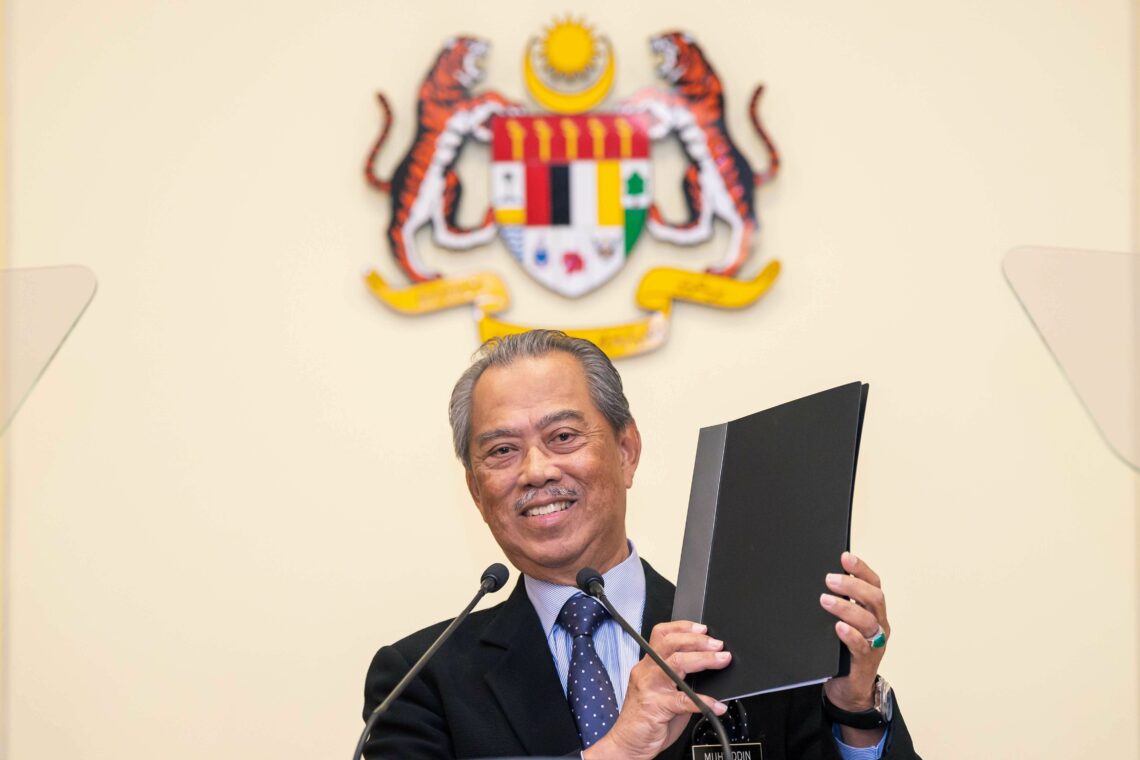

On his very first week as prime minister following a power grab, Muhyiddin Yassin was faced with his first challenge: tackling the COVID-19 pandemic. So far, he has displayed a steady hand steering the country through the new crisis. Coronavirus hit immediately after a period of unparalleled turmoil for Malaysia – a storm of the prime minister’s own making.

After a week of uncertainty in late February 2020, Malaysia’s epic power struggle has overturned the country’s political scene and derailed its leadership succession. Veteran leader Mahathir Mohamad resigned unexpectedly – or, in truth, was outmaneuvered into resigning. A new prime minister, Muhyiddin Yassin, emerged while the former “prime minister-in-waiting,” Anwar Ibrahim, was sidelined.

Malaysia’s most serious political crisis since the race riots of 1969, however, is far from over. The country is still reeling from the shock of this dramatic change. On the surface, calm appears to have returned because of the pandemic. But Malaysian politics has become a choppy sea with strong undercurrents; a tsunami could erupt at any moment.

Ides of March

At the heart of the political intrigue was an attempt to stop the rise of former Deputy Prime Minister Anwar and the Democratic Action Party (DAP), which, in the eyes of the opposition, had been riding on his coattails. The DAP, a secular party that also champions the concerns of Malaysia’s Chinese community, is seen as a threat to the Malay Muslim majority opposition led by the nationalist United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) and the Malaysian Islamic Party (PAS).

Malaysian politics has become a choppy sea with strong undercurrents; a tsunami could erupt at any moment.

Mr. Anwar leads the Malay-dominated but multiracial People’s Justice Party (PKR), which was part of the ruling coalition, Alliance of Hope (PH). The other three coalition members were the DAP, BERSATU (Prime Minister Mahathir’s party), and Amanah (a breakaway party from PAS). These unlikely allies had first rallied around their goal of ending the rule of then-Prime Minister Najib Razak, who was president of UMNO and head of a scandal-ridden sovereign fund known as 1MDB.

The emergence of PH inspired the electorate, which was disenchanted with the sovereign fund scandal. The untested coalition achieved a historic breakthrough, toppling Prime Minister Najib’s UMNO-led ruling coalition in the May 2018 general election. PH could not have been formed without the pivotal political reconciliation between Messrs. Mahathir and Anwar, two former allies turned enemies who then became allies again, motivated by their common goal to defeat the scandal-tainted Prime Minister Najib.

Their surprising reconciliation was made possible by an ingenious power-sharing arrangement in which Dr. Mahathir would be appointed the country’s seventh prime minister while Mr. Anwar, who was then in jail, would be the eighth, should the coalition win ̶ which it unexpectedly did. Dr. Mahathir was to hand over power to Mr. Anwar midway through his term.

While their written pact did not specify the exact date, Dr. Mahathir publicly referred to himself as an “interim prime minister,” referring to the true spirit of the deal, and had even allegedly told Mr. Anwar that the transfer of power would take place around May 2020.

But some opposed an Anwar takeover. Since PH’s victory, various moves had been made by anti-Anwar and anti-DAP groups to portray the parties as detrimental to the interests of the Malay Muslim majority. Mr. Anwar was described as a “liberal,” a dirty word in Malaysian politics, and DAP was deemed anti-Islam. There were voices calling for Dr. Mahathir not to step aside mid-term. Ironically, one of the chief voices against a transfer of power was Mr. Anwar’s own deputy and one-time protege, Minister for Economy Azmin Ali.

Mr. Azmin was already unpopular in the PKR, where he was seen as harboring a secret ambition to be prime minister at the expense of his former mentor. Indeed, Minister Azmin’s ambition was creating a deep split within the party. Due to growing pressure, Prime Minister Mahathir’s stance on the succession question shifted a few times, each time further away from the original agreement. This created political uncertainty, resurrecting old fears among Anwar supporters that the ruling prime minister never had any intention to hand over the position. Things came to a head when PH leaders held a special meeting on February 21, 2020 to resolve the nagging issue of the succession.

The February discussion was a disaster. In the end, Dr. Mahathir was allowed to decide when to step down. But the Azmin-led anti-Anwar forces were not satisfied. On February 23, Muhyiddin Yassin (Prime Minister Mahathir’s number-two in the BERSATU party), and Minister Azmin met at a local hotel, along with their supporters in a show of force. Prime Minister Mahathir went along. In the aftermath of the hotel gathering, Dr. Mahathir unexpectedly resigned as prime minister in protest over his party’s plans to team up with the opposition– a move that amounted to a coup against his own government.

The cause of the resignation later became clear. Mr. Muhyiddin had wanted Prime Minister Mahathir to pull BERSATU out of the PH ruling coalition to form an alternative government with UMNO, PAS and a few other parties. The prime minister opposed the idea of forming a new pact with UMNO, the very same corruption-ridden party he had fought hard to dethrone in the May 2018 election.

Dr. Mahathir’s resignation created a power vacuum that was quickly exploited by Mr. Muhyiddin and Minister Azmin, who launched a coordinated power grab. The former pulled BERSATU out of the coalition to form a new alliance which included UMNO and PAS. Meanwhile, Minister Azmin was sacked from the PKR for betraying the party and pulled his faction of MPs out to join the new alliance led by Mr. Muhyiddin, with the support of the UMNO-PAS opposition. The PH government collapsed.

In the heat of the moment, amid the leadership void, Mr. Muhyiddin alleged to have had the support of the majority of MPs and met with Sultan Abdullah to press that claim. Under the Malaysian constitution, a prime minister can be appointed by the king if he leads the majority party in parliament. Controversially, the monarch swore him in as prime minister on March 1 this year, under circumstances disputed by Dr. Mahathir. The ousted prime minister publicly stated that he felt “most betrayed by Muhyiddin.” The Muhyiddin administration is now perceived as lacking legitimacy, having captured power through a conspiracy that dethroned a democratically elected ruling coalition.

The February discussion was a disaster.

This latest twist in Malaysian politics has been riddled with betrayals and treachery among players once thought to be friends, allies or supporters. It was a strange coincidence that the fall of Dr. Mahathir and the rise of Mr. Muhyiddin took place at the same time of year as the Ides of March – when Julius Caesar was stabbed to death by his trusted senator, Brutus (among others). One Malaysian politician, Ezam Mohd Nor, even likened Mr. Muhyiddin to Brutus.

Scenarios

A possible comeback bid by former Prime Minister Mahathir

In this ongoing political drama, Dr. Mahathir was double-crossed by Mr. Muhyiddin, his party president, while Mr. Anwar was betrayed by his own deputy president, Minister Azmin. The usurpers were brought together by their common ambition for higher positions and their wish to keep Mr. Anwar and the DAP from power.

Mr. Anwar was seen as likely to give too much leeway to the largely Chinese-led DAP. Mr. Muhyiddin was fearful that his party, BERSATU, would not do well during the coming general election if it remained in an alliance with DAP. Mr. Muhyiddin’s goal was to salvage his party’s fortunes by creating an alternative that would appeal to the Malay voters, who are in the majority. Meanwhile, Minister Azmin’s aim was to position himself as the next possible prime minister should Mr. Anwar be out of the picture. Through all this, Dr. Mahathir was trapped between a rock and a hard place and was eventually marginalized. Feeling helpless, Dr Mahathir unexpectedly resigned.

The whole affair could have been avoided had former Prime Minister Mahathir kept his promise to hand over power to Mr. Anwar. His resignation was a major strategic mistake that led to his ouster by Mr. Muhyiddin. Dr Mahathir must have realized his folly and tried to backtrack, but it was too late.

The former prime minister will not easily accept defeat. He is likely to plan a comeback, much like when he came out of retirement to defeat then-Prime Minister Najib. In an interview on March 12, 2020, Dr. Mahathir declared: “It’s not over yet.” But two factors are working against him now.

The first is his advanced age. When he came out of retirement in 2018, he was already the world’s oldest prime minister. Now, at 95, he is running out of time to undertake what would be a long and arduous political battle. He is also running out of allies. He has made too many enemies and shown himself to be a leader who breaks his word.

A possible comeback for Mr. Anwar

Anwar Ibrahim is now at a crossroads. He will have to decide whether to attempt a comeback or chart an alternative future in national politics. His sidelining is a potent blow, and this is the second time he has been “robbed” of his potential premiership. The first was in 1998 during Dr. Mahathir’s earlier tenure, when he was his deputy and “prime minister-in-waiting.” Sacked by the prime minister in what he said was a political conspiracy, Mr. Anwar bounced back as opposition leader, only to agree to join the Mahathir camp again two decades later to topple Prime Minister Najib Razak over the 1MDB scandal. The 2020 affair is his second derailment. However, Mr. Anwar remains upbeat, maintaining what he called his “legendary patience.”

Mr. Anwar could have become prime minister had he, at the height of the maneuvering, agreed to the opposition’s offer to be appointed their prime minister if he abandoned the PH coalition and the DAP. He refused out of loyalty to his allies. But he had also made strategic errors, one of which was to be too tolerant of Mr. Azmin’s political scheming. This patience had caused a deep split in the PKR party, leading to the exit of some promising young leaders. While Mr. Anwar is not likely to remain quiet over the loss of his “crown,” he would need a miracle to become “prime minister-in-waiting” for a third time. In Malaysian politics, however, miracles do happen. Meanwhile, he could play the role of an informal statesman who grooms young PKR politicians for future national leadership.

A rocky road ahead for Mr. Muhyiddin

Many now wonder whether this is the end of the political crisis. Even as Mr. Muhyiddin was being sworn in on March 1, Dr. Mahathir was vowing to put the new prime minister’s legitimacy to the test during the very first sitting of parliament, on May 18. Meanwhile, also on March 1, the PH coalition was filing a police report against Mr. Muhyiddin for “misleading the palace” with his claim that he had the support of the majority of members of parliament.

The prime minister faces tough challenges. Leading a fragile coalition with a legitimacy problem raises prospects of infighting. There could be another power struggle, this time in his own party, BERSATU. And he too risks being ousted. The economy is under severe pressure from the turmoil of the global COVID-19 pandemic. The impact of the crisis will worsen the burning issues of the current political quagmire. In sum, Malaysia’s epic power struggle is far from over.