The future of private military companies

The influence of private military organizations is set to increase in the coming decades.

In a nutshell

- The 21st century has seen a resurgence of powerful non-state armed forces

- Prominent companies like the Wagner group have reshaped modern warfare

- States will struggle to curb the growing influence of these groups

On June 26, 1998, then United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan addressed the Ditchley Foundation’s annual conference in the United Kingdom. He proposed that private security firms, like those that had recently helped restore the elected president in Sierra Leone, might provide the UN with the rapid reaction capacity it needs. He recalled considering hiring a private firm during the Rwandan refugee crisis in Goma to separate fighters from refugees. But he concluded that “the world may not be ready to privatize peace.”

Twenty-five years later, and after many irregular conflicts, perhaps the world is ready. Private militias and contractor groups are increasingly present on the international scene, alongside – or in opposition to – regular armies.

The long history of mercenary forces

In 1648, the Thirty Years’ War came to an end with the Peace of Westphalia. European powers signed two treaties that not only addressed territorial disputes and religious principles but also established the concept of the absolute state. The agreements established the foundation of the modern international system, with each state having exclusive sovereignty over its territory.

Since then, nations and their governments – whether democratic, autocratic, monarchical or republican – have had a monopoly on the use of force. This change catalyzed the establishment of permanent standing armies, marking a departure from the pre-1648 norm of depending on companies of fortune. In the fragmented societies of the Middle Ages, where strong governments were absent and various political actors thrived, mercenaries had flourished, turning war into a lucrative profession.

Warfare shifted from being an intrastate affair to an interstate one. Laws and codes were established to regulate it, and states actively opposed mercenaries, outlawing them as swiftly as possible. The 20th century epitomized this Westphalian ethos.

The post-Westphalian order

The zenith of the Westphalian era was followed by an implosion, hastened by the advent of the technological century and globalization. While the concept of the state with clearly defined territories endured, the internet revolutionized the traditional concepts of borders. In this new world, many governments have begun to show signs of vulnerability. The focus is shifting back from interstate wars to intrastate conflicts.

Amid this weakening of national sovereignty and the emergence of voids in governance, professional soldiers, now referred to as contractors, have started to resurface. These mercenaries, often employed by multinational corporations, are enlisted as supplements to traditional armies, with their services terminated upon mission completion. Their roles are multifaceted: they provide external and internal security, engage in warfare, secure local leadership and even become an extension of that leadership’s armed forces. They also oversee crucial infrastructure like oil wells and mines, and train local forces.

Facts & figures

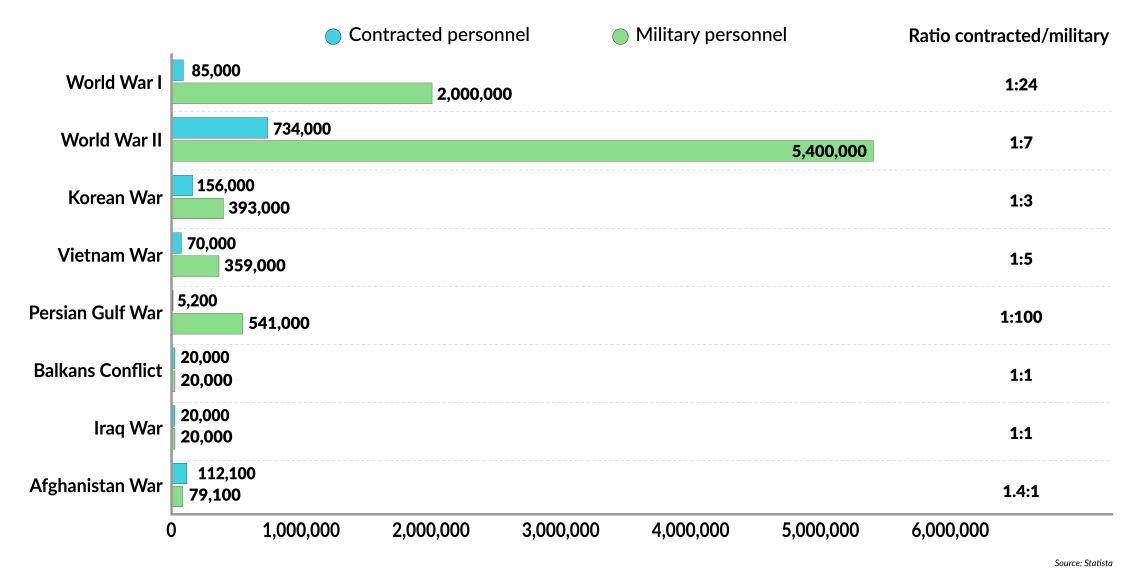

Ratio of military personnel to private contractors in U.S. history

This complex landscape is not solely composed of contractors. There are also other non-state combatants. In some regions, governments have effectively dissolved, giving way to fragmented entities. When a state monopoly on force is impossible, it is replaced by an oligopoly. In these murky areas, new actors emerge, like in medieval times. They seize control of what the state has abandoned, managing it through violence and becoming political forces in their own right. This phenomenon is evident in places like Somalia, Libya, Lebanon and Yemen, where governments are weak and militias operate unchecked. Occasionally, as in the case of Hezbollah in Lebanon, these groups even provide basic services to citizens.

In these undefined spaces, militias and groups of local and foreign contractors move and proliferate, occasionally overlapping or merging, but always driven by the pursuit of profit.

The spread of private military companies

In recent years, one company has notably drawn global attention: the Russian Wagner group, led by Yevgeny Prigozhin until his death in August 2023. Wagner has been involved in unconventional operations, first in Syria, alongside the Russian armed forces, and then on its own across Africa, particularly in Libya and the Sahel region. French and American special forces have had several encounters with the company, often under tense circumstances.

In Libya, Wagner gained notoriety during the siege of Tripoli by Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar in 2019. The group supported the Libyan National Army (LNA), significantly enhancing its capabilities and tipping the conflict in Field Marshal Haftar’s favor. It was only the substantial intervention of Turkish forces – both regular troops and Syrian irregulars – that prevented Tripoli’s imminent fall.

However, Wagner is not the only group of its kind. In Russia alone, throughout the 1990s groups like the Antiterror Orel Group, Ruscorp, Moran Security Group and the Slavonic Corps emerged. These contractors operated not just in Russia but also in the Middle East and Africa, embodying the so-called Gerasimov doctrine, which emphasizes the importance of irregular forces and information warfare. This approach aligns with the ancient strategy of maskirovka – achieving objectives through deception, confusion and instability.

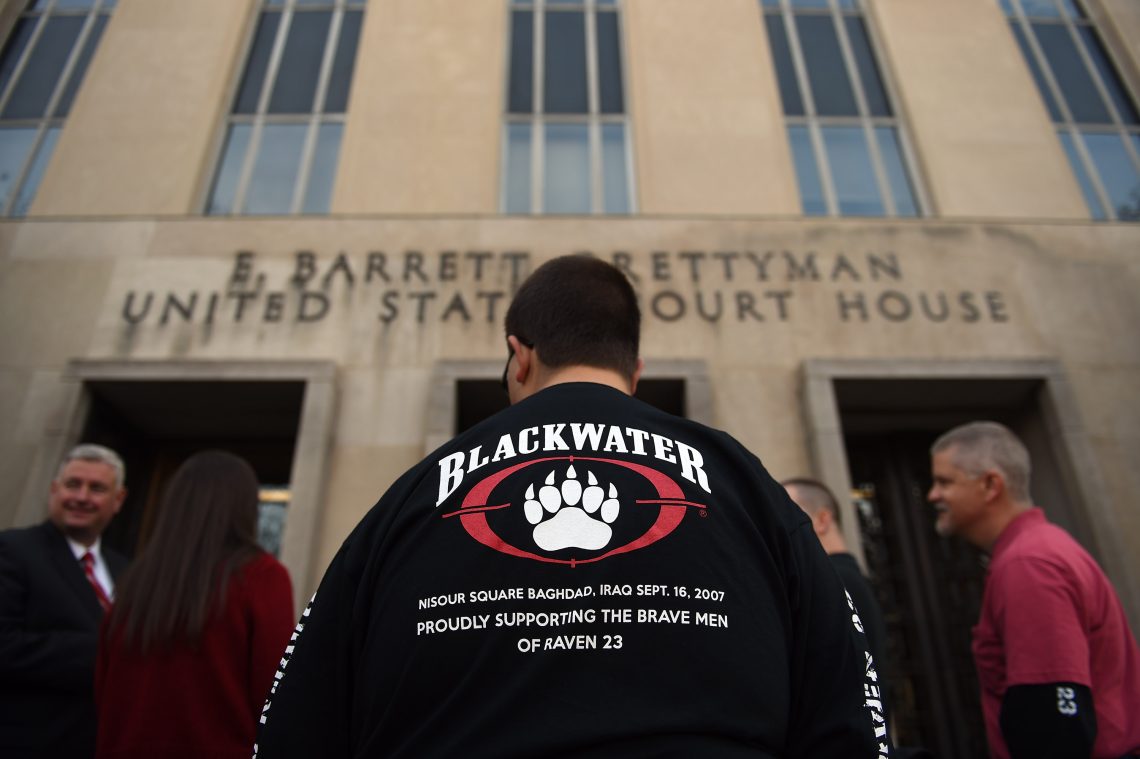

The U.S. has also been a pioneer of private military companies in the new millennium. Erik Prince’s Blackwater (now Academi), Triple Canopy, Titan Corporation and DynCorp are among the most prominent. There are similar organizations all over the world.

More by Federica Saini Fasanotti

The Wagner group’s web in Libya

Niger at the heart of the Sahel crisis

Nation-states and their armies now face new, elusive competitors: private military companies that operate covertly and are often employed by governments for sensitive operations, particularly those scrutinized by public opinion. Between October 2001 and August 2021, 2,402 U.S. soldiers died in Afghanistan, compared to at least 3,500 U.S. contractors, yet the latter received far less attention.

The proliferation of contractors in this unstable, fragmented world is unsurprising given their typically higher salaries. In 2007, during one of the most critical phases of U.S. operations in Iraq, an Army sergeant earned $140 to $190 a day, while private guards from Blackwater or DynCorp made over $1,200 a day. In Afghanistan, contractors accounted for none of the personnel at the mission’s start in 2001, gradually rising to 56 percent by 2010. In Iraq, the number grew from 4 percent in 2003 to 53 percent in 2009.

Scenarios

Less likely: Regulation

Efforts have been made in the past to regulate private military companies, but these have largely been national rather than international initiatives. For instance, Article 359 of the Russian Criminal Code, introduced in 1996, prohibits civilians from accepting rewards for fighting abroad, effectively outlawing mercenary activities. In the U.S., legislation such as the Special Maritime and Territorial Jurisdiction Act, the Patriot Act, the Military Extraterritorial Jurisdiction Act and the Uniform Code of Military Justice includes provisions to control contractors overseas. However, these laws are not applicable to foreign mercenaries.

The UN could attempt to legislate mercenaries worldwide with a global agreement. But the likelihood of this happening is minimal, especially considering the resistance from permanent Security Council members like Russia, who benefit from the use of private military companies.

More likely: Status quo

It is certainly more likely that nothing will be done, and that private military companies will continue to expand in a world increasingly characterized by fragmentation and a shift toward multipolarity. This change marks a stark contrast to the bipolar world of the 20th century. Contemporary wars have evolved from major regular clashes to hybrid conflicts that are complex and difficult to categorize and resolve. An important factor in this new era of conflict is the growing use of artificial intelligence and other emerging technologies in both physical and cyber warfare.

This scenario suggests a future marked by chaos and a lack of unified international governance. The rules of international politics will no longer be dictated by a single power, leading to a more unpredictable and fragmented global landscape.

For industry-specific scenarios and bespoke geopolitical intelligence, contact us and we will provide you with more information about our advisory services.