Putin’s lonely Russia

The fallout of the Kremlin’s war against Ukraine includes Russia’s loss of influence over ex-Soviet republics, which Moscow viewed as strategic buffer zones against potential enemies.

In a nutshell

- Only Belarus’s Alexander Lukashenko supports Vladimir Putin’s war

- China and Turkey are capitalizing on Russia’s weakness in Central Asia

- Russias’s influence will be diminished for many years to come

Of all post-Soviet leaders, only Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko remains loyal to Russian President Vladimir Putin. It is one of the signs that Russia – the former imperial center – is weaker among its formerly conquered countries than it has been for more than a century since the Romanov Empire was falling apart and the Soviet Union had not yet been established, from 1917-1922.

Russia has always been obsessed with the notion of strategic depth, involving the creation of buffer states or spheres of influence. The aim is to keep a potential war front as far away as possible from Moscow and other key cities. In the Kremlin mindset, former Soviet republics are essential for ensuring that NATO or China will not get too close.

From the Russian point of view, the few historical examples of strategic depth violation – by the Poles at the beginning of the 17th century, the French under Napoleon and the Germans under Hitler – were traumatizing threats to the existence of the state. Today, the Kremlin’s flailing invasion of Ukraine is stirring discontent along its western and southern borders.

Over the past three decades, at least eight of the 14 post-Soviet republics have stayed friendly with Moscow, giving the Russian authorities a sense of relative security and control. These nations also provided safe havens for Russian culture, language and trade. In the last few months, however, they have stopped fulfilling this comforting role. Russia’s strategic depth is no longer secured along nearly all its land borders. President Putin cannot count anymore on the former Soviet republics.

Of the ex-republics (besides Russia), the three Baltic states are already in NATO and the European Union. Ukraine is in an open war with Russia while trying to join NATO and the EU, and Georgia and Moldova are seeking a place in the EU and NATO. Elsewhere in post-Soviet space, Armenia refuses to participate in Russia’s war. Yerevan is disappointed with Moscow’s response to its long-standing conflict with Azerbaijan and is looking for new strategic partners. Meanwhile, Azerbaijan and the Central Asian former republics are seizing the opportunity to gain complete independence from Moscow. That leaves Mr. Putin only able to count on President Lukashenko, but not on the Belarusian people.

This revolt of the former Soviet republics, triggered by Moscow’s political mistakes, has deprived Russia of its coveted strategic depth – a layer of buffer states – and its postimperial sphere of influence.

Belarus

The presidential elections in Belarus in August 2020 featured government pressure on all opposition candidates, blackmail and mass fraud in favor of Mr. Lukashenko. Most Western nations do not recognize the dictator’s outlandish claim of victory. His main rival, Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, had to leave the country. Mr. Lukashenko responded to mass protests with a violent crackdown, and many fled abroad. His illegitimacy with his own people and in the West left him more dependent on Mr. Putin to stay in power.

Mr. Lukashenko reciprocated the favor by letting Russia use Belarus as a staging ground for attacks on Ukraine, despite polls showing the Belarusians do not support the war. He has so far resisted pressure from Mr. Putin to formally join the fighting and tie down Ukrainian forces on their northern border. In doing so, the Belarusian strongman exposes his weakness of not being able to ensure that his army would be willing to fight Ukrainians.

Mr. Lukashenko’s vulnerabilities have prompted Ms. Tsikhanouskaya, the de facto president of Belarus in the democratic world, to form a government in exile. In power, this grouping would form an integral part of the anti-Kremlin coalition.

Georgia

Georgia’s paradox is that a decidedly pro-Western society is ruled by the Russian-friendly team of wealthy ex-Prime Minister Bidzina Ivanishvili, which delays Georgia’s integration with the EU. Georgia has become a refuge for many Russians seeking to avoid military conscription or who simply oppose the war and want to escape. Georgians are ambivalent about the Russian influx; some are against while others, particularly in the tourism industry, want to reap the economic benefits.

The government is also conflicted. Prime Minister Irakli Garibashvili and Foreign Minister Ilia Darhiashvili have condemned Russia’s invasion and Georgia’s votes in the United Nations reflect this stance. However, the decision-making center around Mr. Ivanishvili is blocking the imposition of sanctions on Russia, prompting Ukraine to impose economic sanctions on the Ivanishvili family. Georgian Foreign Minister David Zakaliani, however, says Georgia is in full compliance with all financial sanctions against Russia. The internal political stalemate in Georgia hinders the pro-European choice of Georgian society, but also prevents Georgia from actively helping Mr. Putin. Georgians also fear another attack by Russia as in 2008, when it lost 20 percent of its territory – Abkhazia and South Ossetia – to Russian control.

Turkey and Azerbaijan

Two nations whose leaders operate in harmony with each other, Turkey and Azerbaijan, have remained surprisingly neutral in the Russia-Ukraine war. But behind this veil of silence is a plan to rebuild Turkish influence in the Caucasus and Central Asia with Azerbaijan’s help. Azeri President Ilham Aliyev went to Georgia recently with proposals for infrastructure, transport and energy projects. Mr. Aliyev also went to Tbilisi seeking to increase oil exports via the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan oil pipeline.

The most spectacular display of Russia’s weakness in the South Caucasus occurred during the Azerbaijani-Armenian war, which flared up in the shadow of Russia’s attack on Ukraine. For several decades, the frozen conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh guaranteed Russia’s influence in the region: Moscow presented itself as the only intermediary in keeping the peace. Azerbaijan wants peace in Nagorno-Karabakh, which it claims as its own territory, but on its own terms.

Armenia found political support from Nancy Pelosi, the speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, who visited Yerevan and met with Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan. An actual Armenian-Azerbaijan peace accord may now happen under Turkey’s auspices and with the United States’ quiet blessing.

Central Asia

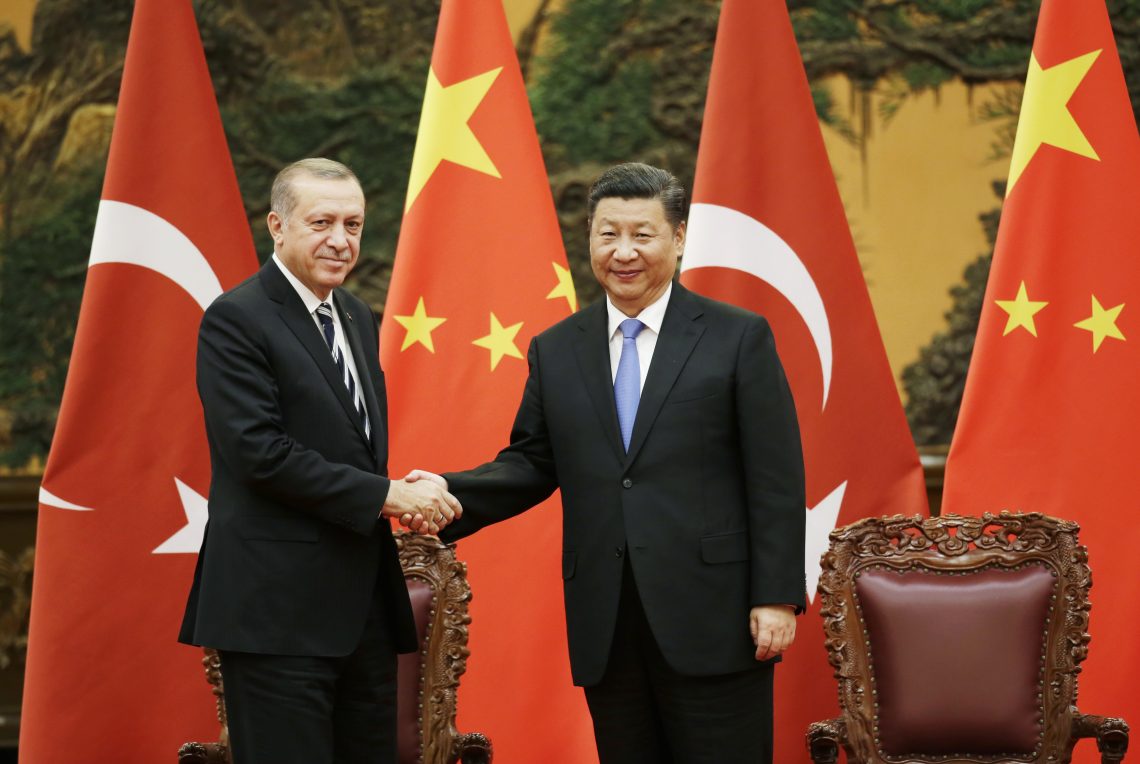

The weakening of Russia’s position in Central Asia was on display during the September 2022 Shanghai Cooperation Organisation Summit held in Samarkand, Uzbekistan. Mr. Putin invited Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan to participate as a “partner in dialogue.” During the event, China’s rising influence in this organization and its dominance over President Putin became clear.

The Kremlin autocrat also faced other snubs, such as waiting for the tardy Kyrgyz President Sadyrem Japarov. Soon afterward, Kyrgyzstan joined other ex-Soviet republics in adopting the Latin alphabet and dropping Russian-based Cyrillic, a symbolic breaking of cultural ties with Russia.

Russia’s loss of influence in the post-Soviet buffer zone is a major setback for Mr. Putin.

The increasing importance of Turkey is worth watching. In March 2022, Mr. Erdogan participated in a meeting of the High-Level Strategic Cooperation Council in Uzbekistan and signed nine agreements, including preferential trade and military cooperation. A month later, Turkey concluded a similar deal with Tajikistan, whose leader publicly admonished Mr. Putin to show more respect to his Central Asian partners.

These developments took place against a backdrop of rising internal disputes within Central Asia that Mr. Putin has been powerless to prevent or stop. One of them included a clash between the forces of Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan in a dispute over borders and smuggling.

Kazakhstan

Russia’s influence in Kazakhstan, the most powerful country in Central Asia, is probably weakening the fastest. The sidelining of longtime ex-President Nursultan Nazarbayev seemed to open the way for Russia to exert greater influence. Instead, Kazakhstan under President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev is taking a political turn toward China and Turkey. Its ultimate choice of allies will influence the rest of Central Asia.

Kazakhstan is justifiably worried that Russia will make territorial claims on Astana for the northern part of the nation. But China came to the rescue by guaranteeing Kazakhstan’s territorial integrity in a visit by Chinese leader Xi Jinping. Declarations of this kind would usually be considered interference in the Russian sphere of influence. Instead, the Kremlin pretended not to hear Mr. Xi’s statement.

Scenarios

Russia’s loss of influence in the post-Soviet buffer zone is a significant setback for Mr. Putin. The loosening of the imperial vise because of Ukraine has shaken up the “frozen conflicts’’ long exploited by Moscow. The most spectacular example is the intensification of the war between Azerbaijan and Armenia over the disputed region of Nagorno-Karabakh, and the reactivation of numerous internal conflicts within Central Asia. The national ambitions of individual states will likely intensify. Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan have the best chances of maintaining greater stability in this volatile period.

Russia retains a strong position in culture, politics and networks of agents, but its attractiveness is greatly diminished after losing its ability to control or shape events.

After the chaos subsides, former Soviet republics in Central Asia and the Caucasus will look for new political patrons. While China and Turkey are standing as neutral in the war between Russia and Ukraine, China is closer to Russia, and Turkey has a greater understanding of Ukraine. Meanwhile, China and Turkey are rapidly gaining influence in these regions at the expense of Russia. The U.S. is also seeking more influence, partly to thwart Iran’s ambitions.

If the war seriously weakens the Russian Federation to the point of radical decentralization or partial disintegration, Turkey and China will take the political initiative by granting security guarantees and submitting business proposals. China wants to enhance its Silk Road, which requires new allies from Asia to Europe.

If the war ends by next summer and Russia remains intact, it will still take many years for the Kremlin to rebuild influence in its post-Soviet neighborhood. The West actively courts nations seeking a geopolitical path away from Moscow.

These processes will probably put several countries in Central Asia and the Caucasus in a devilish dilemma: whether to take advantage of the West’s soft power or build hard ties with China and Turkey. For now, however, the only apparent reality is the collapse of Russia’s influence among post-Soviet states because of its war against the second-most populous of them, Ukraine.