Russia breaks its social contract

Russian President Vladimir Putin has ensured stability by offering Russians an implicit social contract. Now, the country’s deepening financial crisis has put an end to this, forcing the government to increase taxes and raise the retirement age. No matter how cleverly handled, these austerity measures could trigger a serious backlash.

In a nutshell

- A demographic trough and rising life expectancy are straining Russia’s finances

- Raising the retirement age is politically risky and may provide only limited fiscal relief

- Even if carefully handled, the reform could produce a broad groundswell of discontent

Russia’s domestic policies began to shift almost immediately after the predictable outcome of the presidential election. The initial changes (more are certain to follow) are so serious that they must necessarily entail political adjustments as well. They strike directly at the implicit social contract that has formed the basis of Russia’s stability over the past two decades, according to which the state authorities are given a carte blanche by the people in exchange for a certain minimum standard of living and social protection – modest enough for developed countries, but quite substantial compared to the Soviet and early post-Soviet past.

Now President Vladimir Putin has taken a sword to the sacred cow of his regime – a social safety net inherited from the Soviet past that was untouched even during the shock therapy era of the early 1990s. The retirement age will be quickly increased from the current 60 to 65 years for men and from 55 to 63 years for women. The so-called “social retirement benefit” paid to all elderly people, even those who were never employed or contributed to the Retirement Fund, will now be made only to men and women who survive until they are 70 and 68, respectively.

Demographic trough

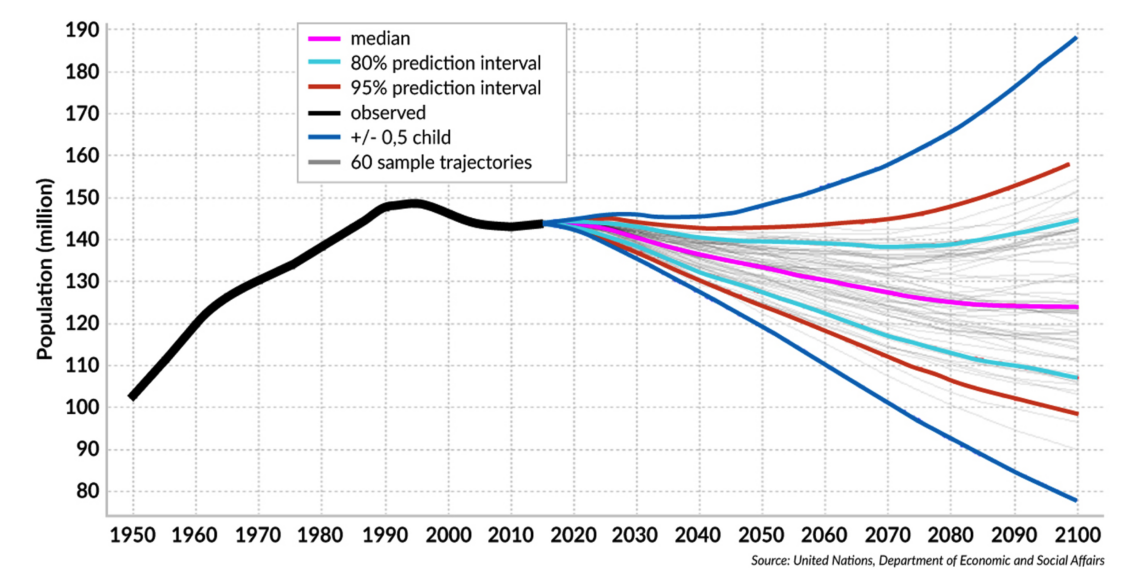

Russia’s demographic and financial situation has made this reform – or something like it – inevitable for quite some time. By 2030, Russia’s population will decrease by 3.3 percent, and by 2050, by 10.4 percent from today’s 146.9 million, according to a 2017 forecast by the United Nations. This depopulation trend cannot be reversed by immigration, since both the authorities and the public are anxious to limit it. In any case, Russia is not a destination for the global migration flow, which is directed to more attractive countries.

At the same time, the average life expectancy for Russian men and women has grown quite significantly, from 59 and 72 years, respectively, in 2000 to 67.5 and 75.6 in 2017; by 2030, government forecasters expect it to rise to 70.5 and 79.6 years. The decrease in population is therefore not connected with a rising mortality rate, as had been the case in the immediate post-Soviet period. Instead, it is an echo of previous “demographic troughs” – dramatic plunges in birth rates and rises in death rates caused by collectivization, industrialization and the Great Purge in the 1930s; World War II in the 1940s, and “shock therapy” in the 1990s.

Facts & figures

Russian Federation: total population

As Russia enters another demographic trough, the unborn children of the 1990s will not be entering the job market. Retired people now make up almost a third of the population, with each being supported by just 1.68 working people. Further deterioration of this ratio is inevitable. According to government forecasts, by 2030 the total number of economically active Russians will decrease by approximately 8 percent; in the 16-39 age cohort, the decline will be 25 percent. Even a highly efficient economy could not withstand such pressure, and Russia’s labor efficiency is the lowest of any OECD country except Mexico’s. Such negative demographic trends are impossible to reverse quickly. This leaves no alternative to retirement reform.

Financial fear

The reform’s second context is the Russian government’s deep fear of depleting its financial resources – dramatically magnified by the lack of any real prospects for renewing normal relations with the West. For this reason, the retirement reform was accompanied by a decision to raise the value-added tax (VAT) rate from 18 to 20 percent.

Today, this levy provides the government with about one-third of its revenue, if one excludes income from oil and gas exports. The VAT increase is expected to bring an extra $10 billion into the budget every year. It is not a very radical step, especially since Russia had already used a 20 percent VAT rate from 1993 to 2004. Yet the tax hike will have a one-off, across-the-board inflationary impact on consumer prices. Combined with the higher retirement age and lower old-age benefit, it will have a clearly negative impact on household income.

Political risks

The timing for these painful measures was chosen perfectly. Russia’s presidential elections are over, and the next parliamentary election is more than three years away. The media are careful to present the reforms as purely the idea of Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev’s government; Mr. Putin had absolutely nothing to do with them.

Even so, the political risks are huge. The limits of the public’s trust in President Putin are untested, along with its willingness to combine that trust with a belief that the government can do anything apart from or against his will. Mr. Putin himself has spoken many times against raising the retirement age, notably in 2005, when he said flatly that “this decision will not be taken while I am the president.” A YouTube video of this statement has now gone viral in Russia. Perhaps the Russian public’s trust in their president is limitless. But what if it is not?

Even if Mr. Putin can be insulated from the backlash, the reforms are still risky to the government.

Even if Mr. Putin can be insulated from the backlash, the reforms are still risky to the government. Public opinion is not particularly swayed by rational arguments, and financial reasoning will almost always be overcome by appeals to emotion. Even on the merits, there are serious economic questions about the reform. It will produce an immediate glut of workers over the age of 55. Russia’s job market has not been kind to such people – finding an attractive job is already problematic for anybody over the age of 40.

Economic risks

In developed countries, median wages tend to rise steadily until the moment of retirement. In Russia, however, earnings peak at age 45-50, then drop off sharply. A sudden increase in the labor supply of 50- and 60-somethings will completely disrupt the job market – at least in the official economy.

One of the biggest achievements of Vladimir Putin’s rule has been a huge and largely successful effort to drag workers and their salaries out of the unregistered “gray” economy. Now their return to the shadows is quite likely. For most men, paying contributions into the Retirement Fund may seem senseless since they have barely an even chance of living until retirement age. (In 47 of 83 Russian regions, the average life expectancy for men is lower.) Evading taxes is easier by dropping out of the official economy and evading them in bulk.

The other risk is an explosive rise in official unemployment. Throughout the post-Soviet years, joblessness was consistently kept very low – at about 4 percent of the economically active population, according to the International Labor Organization. Those who formally register in job centers and receive unemployment benefits are even fewer, at less than 1 percent. If this number increases dramatically, the state’s financial obligations will grow as well.

But no matter what ordinary Russians do – flee to the gray economy or register as unemployed – much of the reform’s positive effect will be neutralized. Either revenue to the state budget will decline or expenditures will increase. Most likely, both will happen.

More equal than others

The breathtaking cynicism of certain aspects of the retirement reform also poses risks.

Millions of Russians are entitled to early retirement — usually after 20 to 25 years of employment. They belong to several broad categories. The first concerns people who work in hard or dangerous conditions (such as miners) or are otherwise protected (mothers with large families). The promise here is that they will be exempt from the reform.

A second category covers physicians and teachers, along with cultural workers such as actors, ballet dancers and other artists. They are not so lucky, as their “special” retirement benefit is only supposed to kick in after they reach 68 (men) and 63 (women) years of age.

Finally, there are the military, police and other civil servants (including employees of the security, control and surveillance services; courts and public prosecutors; the Ministry of Emergency Situations and others). There are millions of such people, who generally receive retirement pensions several times larger than ordinary employees. Their pension eligibility often starts at age 50, 45, or sometimes even 40. In their peak earning years, they can use these pensions to supplement other earnings.

Because the state clearly distinguishes between first- and second-class citizens, the retirement reform is not supposed to touch these people at all. As mentioned, most of these civil servants can retire early with pensions that are a multiple of what the state pays ordinary employees. Against this, plans to include a 7 percent cost-of-living increase in retirement pensions (which currently average the equivalent of $222 a month) amount to a pittance.

The unions are being offered an opportunity unique in recent Russian history to become political players.

Winston Churchill used to call British civil servants “our uncivil masters”; present-day Russians use much ruder names for them. Unequal treatment under the retirement reform will only increase the significant social tension between “the people” and “the authorities” – even if Mr. Putin himself is exempted from that multifarious and faceless category.

Usual suspects

Not surprisingly, the reform is a political orphan. Nobody publicly supports it, apart from the government and deputies from the ruling United Russia party – many of whom would support any top-down measure, including orders for their own public execution.

There are plenty of opponents, however – none with even the slightest influence. They include:

- The parliamentary opposition, especially the communists, who are looking to score a few popularity points by condemning the retirement measures

- The non-parliamentary opposition, including Alexey Navalny, who is using this hot topic to draw attention to himself and organize a new round of protests (even though he himself proposed raising the retirement age back in 2014)

- The regional authorities and legislatures, even though they are required by law to submit opinions on government bills. In this case, they have done so with evident reluctance – since the decisions are made in Moscow, but they will be held responsible by the central authorities and the public

A partial exception to this rule may apply to the trade unions, which have been traditionally inert and obsequious. The official unions are even organizing rallies against the proposed measures and speaking with unusual vehemence. Mikhail Shmakov, the head of the Independent Trade Union Federation since 1993 and a trusted Kremlin loyalist, wagged his finger at “governors, mayors, deputies at all levels [who] support the government version of the retirement reform,” noting that they all face regional elections every September.

Indeed, it is the unions – especially the ones that are truly independent and not part of the official federation – that are being offered an opportunity unique in recent Russian history to become influential political players.

Diffuse revolutions

This opportunity is important, because unhappiness about the government’s actions is becoming mass-scale and acquiring a precise focus. A petition against raising the retirement age on Change.org (a resource that is very popular in Russia and closely watched by the authorities) has acquired almost 3 million signatures in a month, even though the Russian Confederation of Labor, an independent trade union that sponsored the campaign, has only a few thousand activists.

The danger is that protests will spread while remaining unstructured and devoid of a coordinating center.

The main danger for the central authorities is not that someone will step in at the head of the protest, but that it will gain strength while remaining unstructured and devoid of a single coordinating center. The longer this process continues, the more dangerous it becomes. The regime can deal efficiently with specific opponents it can identify. Diffuse discontent and a resultant broad rejection of legitimacy is something it has not encountered yet.

The legitimacy of Russia’s political system and Mr. Putin personally have lost their connection with any hopes for a better future. Even the fear of a return to the horrible past, which has Russia’s elite trembling, is of no great concern to the populace. The main source of regime legitimacy today is simply the lack of alternative solutions. On specific issues, Russians are quick to voice their discontent with the authorities. However, these comments are still followed by the dejected question: “But if not him, then who?”

A key question is whether the alternative could be simply removing the discredited ruling group and its sovereign lord, without considering who would replace them. Personalistic regimes in the post-Soviet world have been dismantled in a variety of ways. Sometimes the new face of government is known beforehand (Like Mikheil Saakashvili in Georgia or Viktor Yushchenko in Ukraine). Sometimes it appears suddenly from a street revolution, like a jack-in-the-box (like Nikol Pashinyan in Armenia). Sometimes the leader only emerges after the regime change, when the winners are dividing up the prize (like Petro Poroshenko after Ukraine’s Maidan revolution). The important point is that a single figure to rally the opposition is not a prerequisite for regime change.

Rulers on trial

Those risks are certainly recognized by the authorities. It is quite evident that the retirement reform was deliberately announced in its harshest version, with the intention of significantly watering it down in the autumn, during parliamentary debate. President Putin will almost certainly play a leading role in this process. It is significant that Mr. Putin’s media spokesman, Dmitry Peskov, has already been asked whether the president would veto the retirement age law – and that he replied, with great relish, that it is too early to say.

At some point, even the Russian public becomes immune to jingoism, and that point may have been reached.

In any case, before these emergency austerity measures become a trial for Mr. Putin, they will be a trial for Mr. Medvedev. The prime minister will be the guinea pig in this policy experiment. If he succeeds in implementing the reforms in close to their original shape, Mr. Medvedev’s position could become almost unassailable and he may dare to turn his ambitions to something bigger. If he fails, he will play the familiar kamikaze role that the Russian public often ascribes him – make as many irreversible decisions as possible and then leave. In that case, the man who replaces him would be Mr. Putin’s most likely successor – assuming there is no radical regime change in the meantime.

The Russian authorities have another tried-and-tested way of reducing the domestic policy risks: a new military campaign. But with each attempt to show the superiority of guns over butter, the required commitments grow. After Crimea, Ukraine and Syria, it is simply not possible to keep raising the stakes all the time. At some point, even the Russian public becomes immune to jingoistic pressure, and that point may even have been reached.

The first results of this grand political maneuver will become visible in the fall, when football fever and the holiday season is over, and when the usual seasonal surge in consumer prices gathers momentum. As parliament begins deliberations on the government’s tax and retirement decrees (the latter passed its first, pro forma reading on July 19, supported only by United Russia), possible scenarios for future developments will begin to take shape. The menu will remain quite broad, but it will contain many more bad options than good.