Quantitative easing and the problem with pensions

European central banks’ quantitative easing policies have allowed governments to avoid reforming their public pension schemes. The financial burden on the young is huge – and the question of financing retirements may soon become a relevant political issue.

In a nutshell

- Quantitative easing halted the drive toward pension reform

- Current monetary policy hurts private pension funds, public schemes are inefficient

- The highest burden is on the young, who struggle to finance their retirement

In the early 1980s, Chile introduced a privately managed pension scheme, based on individual capital accounts. Though no country in Europe decided to go for a full-fledged private system, the Chilean model and an overall desire to put public finances in order inspired many pension reform drives on the continent. Pay-as-you-go pension systems – in which the benefits being paid out are funded by taxes on the currently working population – are difficult welfare programs to reform. Attempts to change them must overcome strong vested interests.

Still, countries throughout Europe undertook such reforms. Broadly speaking, they transformed solely pay-as-you-go models to mixed systems, from defined benefit to (at least partially) defined contribution schemes. Instead of going for full privatization, like Chile, European countries added second and third “pillars” to their pension systems, which were based on voluntary private pension accounts, as well as private pensions that were funded both by employees and employers.

Facts & figures

Pension terminology

Pay as you go

When used to describe pension schemes, this phrase refers to systems in which the money currently paid into the system by working people is distributed directly to those already in retirement.

Defined benefit

Defined benefit systems set a concrete amount that a pensioner will receive at retirement, regardless of the amount paid in.

Defined contribution

Defined contribution systems allow an individual to decide how much to pay into retirement savings. The pension payout is based on that amount.

The drive for reform came from a fear that the welfare systems were untenable. Public finances were becoming increasingly precarious and demographic trends undermined the viability of pay-as-you-go schemes. There was strong political opposition, but in most countries consensus was reached that pension systems should include some degree of private investment.

Central banks gain power

Quantitative easing (QE) programs – in which central banks buy government bonds to inject money into the economy – allowed policymakers to prolong unsustainable measures. Most central banks in Europe have been engaging in this once unconventional monetary policy over the past 12 years.

For governments all over the world, this meant a (supposedly) temporary suspension not only of fiscal rules, but of market checks on their finances. Central banks have de facto financed unprecedented levels of public spending, with only the vaguest commitment to bring balance back.

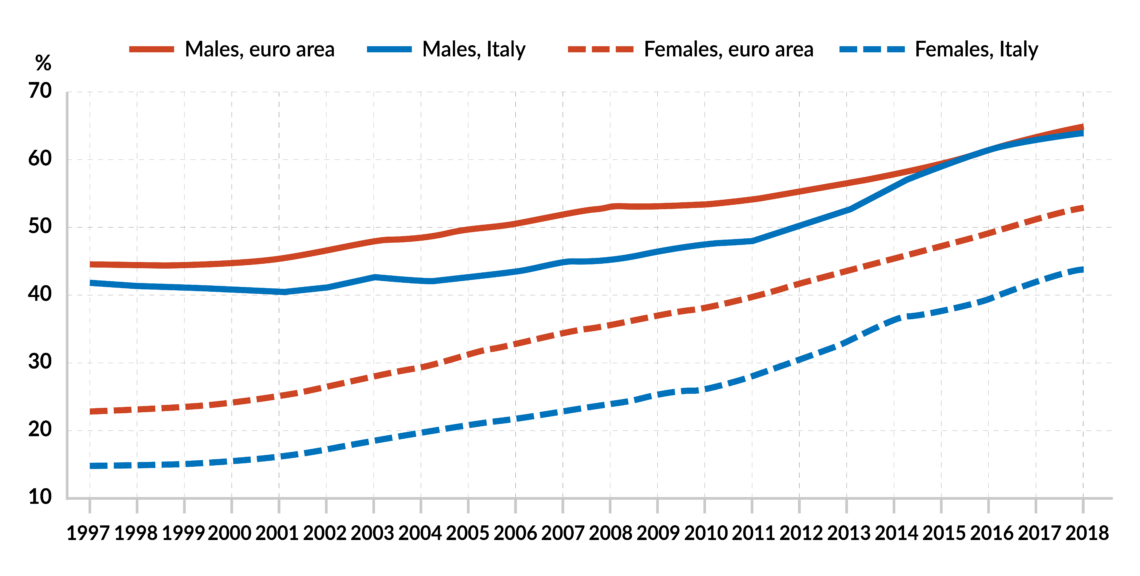

The case of Italy is telling. In 2011, amid the storm of its debt crisis, the country was entrusted to a caretaker government led by former European Union Commissioner Mario Monti. Prime Minister Monti and his cabinet were quick to pursue pension reform, which sharply raised the retirement age. Proving that it could reform its system was crucial for Italy to regain credibility and improve its market access, as well as to reduce the budget deficit.

Seldom a day passes without central banks being asked to “do something” to stabilize markets and avoid political turmoil.

But as the European Central Bank ended up owning about 20 percent of outstanding Italian government bonds and financing the additional 20 percent owned by Italian banks, prices signaled faith in the powers of the ECB rather than worries about Italy’s finances.

Artificial incentives

After the Covid-19 pandemic hit, both the ECB and the United States Federal Reserve made clear that they would continue quantitative easing for the foreseeable future. With governments increasing borrowing and spending to cope with the sharp decline in economic activity, central banks are bound to remain in the driver’s seat.

Seldom a day passes without central banks being asked to “do something” to stabilize markets and avoid political turmoil. Before Covid-19, voices critical of such a prominent role for central banks were sometimes heard. The pandemic has made clear that there is no path back to the old consensus. The principle of central bank independence is becoming increasingly tenuous by the day.

For Europe, this has brought financial and political consequences. On the financial side, pension funds have been complaining about the negative side of Quantitative Easing for years: low interest rates and low returns for a long time, at least nominally. Quantitative Easing artificially makes government bonds more attractive and limits the interest paid on them.

Facts & figures

Pension funds hold enormous amounts of government bonds. The drop in yields causes a direct financial loss to the funds and, more importantly, lowers (or even eliminates when interest rates are negative) the income generated by savings investments. This is called “financial repression” and reduces the amount that private funds can pay out as pensions.

Meanwhile, the low interest rates effectively increase pension liabilities. This leads to deficits that will ultimately need to be financed somehow, likely by higher contributions.

Burden on the young

Central bankers have long defended Quantitative Easing as “neutral” when it comes to pension funds. In the short term, Quantitative Easing drives asset prices up, meaning returns should rise with capital gains. In theory, this should balance the increase in liabilities that is implied by the drop in government bond yields. In practice, there are questions about how much balance can really be achieved.

It could be that retirees are benefiting in the short run, but less so in the medium term. Quantitative Easing could particularly hurt those who have paid in only a few years of pension contributions. Younger people may see interest rates rise again, but in the distant future. The years of their career spent in a “normal” financial environment may be too short to provide them with the pension they expect by enrolling in a private scheme.

As an insurance CEO commented to this writer, we will “undoubtedly” witness a reduction in private pensions, which will bear more heavily on people between 30 and 40 in the coming years, who will have to rely on current savings and current investment returns and not on accumulated capital.

The monetary policy of financial repression induces investment to shift from bonds to equity risk.

Young members of the workforce face a poorly performing economy burdened with government regulation and high taxes – which tend to reduce income, employment and productivity growth. On top of that, interest rates are close to zero and prices for healthcare are rocketing. All these factors may make it nearly impossible for a 35-year-old to accumulate enough savings to finance a comfortable retirement.

The monetary policy of financial repression induces investment to shift from bonds to equity risk (the risk of owning an asset or a business, not a contractual interest rate). This includes everything from real estate to a nail salon, to private equity, to Bitcoin, to a stock market index fund, to gambling.

A good parable is the unemployed youth investing stimulus checks in stocks that have become popular among some communities on the internet, as with GameStop earlier this year. The risk associated with such decisionsis clear. The question is if the public has gained an increased awareness and tolerance for risk, or whether it will demand more government help if these investments lose money.

Quantitative Easing and pension politics

This brings us back to the political consequences. With the second and third pillars of the pension system based on less-well performing, more expensive private systems, pressure to pump money into the public pillar will rise. The increased burden will necessarily fall on working people to finance payouts to current retirees.

It is easy to imagine a scenario in which current and prospective pensioners’ demands become a central political concern. In many ways, it will be a reversal of the situation in the 1990s and the early 2000s, when the focus was on the disproportionately high pensions paid to special interest groups with political leverage. Pension reforms were fueled by worries about demographic imbalances, growing public debt and the corruption perceived to be embedded in the pay-as-you-go systems.

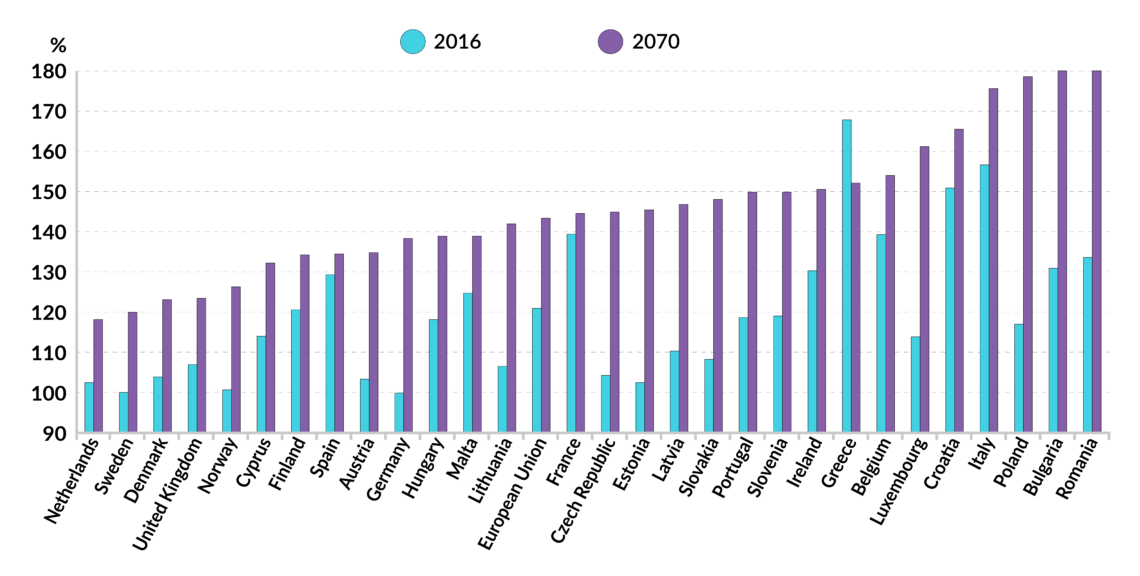

Facts & figures

Now, we may see people increasingly worry about their own future income. Raising the retirement age is always politically risky. Again, Italy provides a good case study. Over the past few years, Italian governments have twisted the pension system, partly undoing the effects of the previous reforms. For example, since 2017, the effective retirement age has been lowered for people in jobs deemed hazardous or arduous (like mining and teaching), for women and for those who are 62 years or older. All of these have effectively raised public spending on pensions.

Public, pay-as-you-go systems have the virtue of being easier to manipulate if a country needs to increase pension payouts but does not have a growing workforce to bear the weight of rising contributions. The answer is direct government financing, through higher taxes or deficit spending.

That solution could lead to intergenerational tension. Younger people would be left with less savings, lower pension benefits, later retirement, higher taxes and additional per capita debt. This provides fertile ground for a politician to mobilize the youth around these issues.

Libertarian mavericks who worry about the increasing power of central banks dream of preventing this scenario by fomenting political opposition to Quantitative Easing as its negative effects become more apparent. However, Quantitative Easing has risen in popularity over the last few years. Central banks’ intervention has proven a formidable tool for providing politicians with room to maneuver in a crisis.

The Dutch example

Another possible scenario could emerge if growing government debt breeds more concern over public finances and a new urgency to reform pension systems.

The case of the Netherlands shows that outcome is not entirely unlikely. The country is set to reform its pension system again, subject to parliamentary approval. Starting in 2026, pensions will no longer be accrued in defined benefit schemes. Instead, the only option will be defined contribution schemes in which people pay in at a flat rate. The Dutch see this as a necessary step toward reducing intergenerational redistribution from the young to the old. The reform has a large degree of support among political and social actors.

The Dutch see reform as a necessary step toward reducing intergenerational redistribution from the young to the old.

The Netherlands is a relatively frugal Nordic European country, whose public finances are kept in reasonable order. In Mediterranean countries, pension reform proposals cause turmoil. In France, changes enacted by President Emmanuel Macron were met by a wave of strikes. Countries that Quantitative Easing has particularly benefited will be the last to question its legitimacy.

Outlook

Pension reforms now are thus part of a larger question: Will central banks ever return to their pre-2008 modus operandi? If so, we will see new attempts to reform the system. Private pension funds may regain robust profitability.

If the answer is no, the change in political priorities and institutional settings will be even more profound than we have seen in recent years. A creeping return of government-funded pensions would then be the most likely scenario.