The hidden repercussions of public debt in the West

Europe and the U.S. share a common commitment to monetization: central banks in the West buy much of the public debt. However, while the share of European bonds in the hands of non-European investors is limited, the portion of U.S. Treasuries held abroad is significant.

In a nutshell

- The U.S. and Europe have monetized their debt on a huge scale

- The trouble this causes for the EU is likely to remain in the bloc

- China is unlikely to stop buying or sell off U.S. debt

Over the past two years, many countries in the West have relied on public debt to sustain their economies. Two policy choices have contributed to this phenomenon. First, central bankers have kept interest rates at or near zero to promote growth and make it easier for governments to pay interest on their existing debt. Second, the Covid-19 pandemic and the restrictions that followed have opened the gates to generous public expenditure: in the short run, to help those in trouble, and in the medium term, to jump-start the economy.

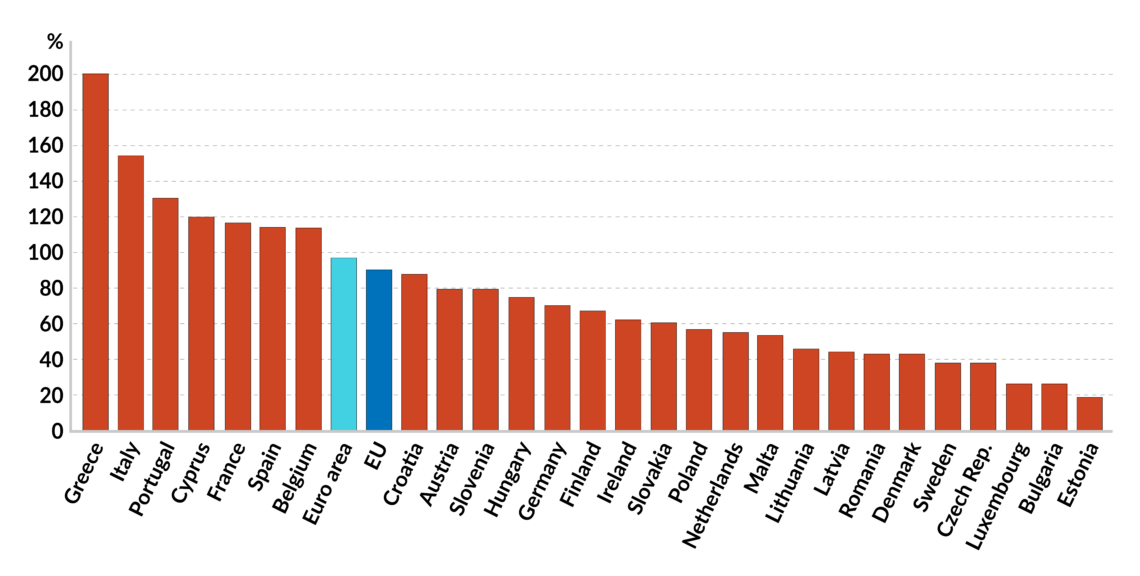

In the eurozone, the ratio of debt to gross domestic product (GDP) rose from 84 percent in December 2019 to 97 percent in the third quarter of 2020. The figure is striking in several countries: 200 percent in Greece, 154 percent in Italy and 116 percent in France. Under normal circumstances, a debt ratio is considered concerning if higher than 60 percent, and unsustainable if more than 100 percent.

Though the U.S. economy has performed better than Europe’s, its debt story is worse.

Manipulating interest rates worked well until the end of 2019, enabling most eurozone countries to cut their debt-to-GDP ratios, although its effect on growth was weak at best. However, this backfired in 2020, when low interest rates encouraged countries to increase public spending and justified a commitment to further expenditures.

Although the United States’ economic performance over the past few years has been better than Europe’s, the American debt story is worse, since the debt-to-GDP ratio rose from 107 percent in the third quarter of 2019 to 127 percent in the fourth quarter of 2020. That number is bound to increase if the new administration keeps its promises about expanding the size of government.

A European problem

In general, high levels of debt involve three sets of challenges. One regards growth. Public debt usually finances a higher level of expenditure, rather than a drop in taxation. Thus, higher debt reflects the expansion of the public sector at the expense of the private sector. The result is more inefficiencies and lower growth, which often provokes even greater expenditure.

A second problem concerns debt servicing. As long as interest rates stay low, debtors do not have to worry about their liabilities. But they might be sitting on a time bomb that will explode as soon as interest rates start rising. For example, the interest rate on 10-year U.S. Treasury bonds was slightly more than 0.9 percent at the end of 2020, but had risen to 1.6 percent by early March. The rise roiled financial markets, but they calmed down after the release of good economic growth and jobs figures, and after the U.S. Federal Reserve sent reassuring messages that it would keep money cheap. Still, things could get out of control once yields cross the 3 percent threshold.

Facts & figures

The third problem focuses on creditors. This is where the European Union and the U.S. differ. Although the data about Europe is incomplete, in 2019 nonresidents held about half of the debt issued by eurozone governments. In particular, the share was about 50 percent for Germany, France and Spain, and about 30 percent for Italy.

However, these figures are misleading, since most nonresidents are actually residents of other EU countries. In fact, scattered evidence suggests that the amount of European government debt held outside the EU is limited. The lion’s share of this debt is issued by a small number of countries, especially Germany. The purchases of new debt are modest, since interest rates are extremely low – at zero or even negative. The only significant buyer is the Swiss Central Bank, which traditionally resorts to buying German government debt to prevent the Swiss franc from appreciating.

Europe’s public debt is therefore a European problem: a crisis in any member country could have political repercussions on the EU project. Yet unless it were to bring down the entire EU (an unlikely scenario), a debt crisis in a single member state per se would have limited effects on the wider geopolitical scene.

Many would like to see Brussels issue its own “Union bonds,” but is not clear who might buy such low-yield bonds outside Europe. At present, only China and the U.S. government are potential buyers – possibly becoming creditors in exchange for political commitments or economic concessions. The EU is not able to concede the former, because foreign policy is still a national matter. The latter could mean lower regulation, taxation and trade barriers – a positive, but something Brussels may be loath to grant.

Demand for treasuries

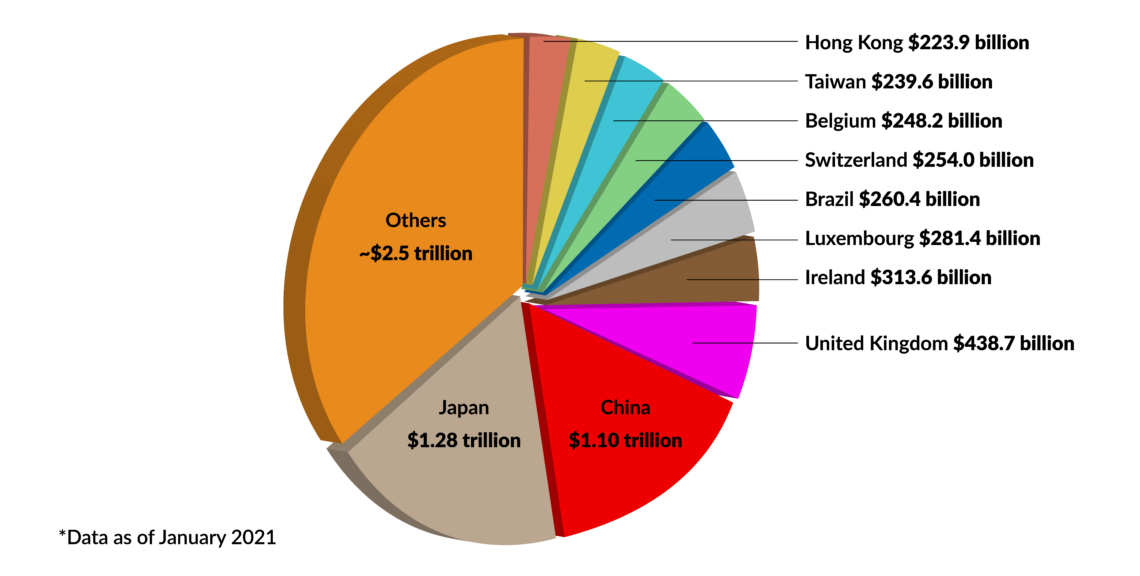

Now, let us turn to the U.S. According to mid-2020 data, about 62 percent of U.S. debt was held by the Federal Reserve and various American governmental agencies; over 26 percent was in the hands of foreign investors (the largest single creditors are Japan and China) and the remaining portion (12 percent) was held by the American public.

Rather than raising funds from the public, the government has resorted to asking the Fed to increase the money supply.

Not unlike what has happened in Europe, the debt strategy followed by successive U.S. administrations has been implicit monetization. Rather than raising funds from the public, the government has asked the Fed to increase the money supply, and the central bank has obliged. It seems unlikely to ask for its newly created money back. In fact, the Fed has already hinted that it stands ready to monetize further debt, if necessary.

The position of the other actors – residents and foreign creditors – is more complicated. The main reason that the public has purchased a significant amount of treasuries is precisely because the government has chosen to monetize its debt. A large share of the new money created by the Fed has ended up in the hands of American savers, who have used it to buy stocks (thereby inflating a Wall Street bubble). They then purchased treasuries to balance their portfolios.

Facts & figures

If the Wall Street bubble bursts, the demand for treasuries will probably rise further as investors rush to safe assets. The deal between the administration and the Fed has created artificial demand for treasuries that will intensify if stock markets fall. There is one important caveat, however. If prices were to rise – inflation is predicted to stay at 1.4 percent in 2021 – it would become more difficult to persuade the public to buy treasuries, pushing up yields.

The size of foreign-owned U.S. debt is of course larger than Europe’s, but not necessarily more problematic. The largest creditors are Japan, China and Europe, each holding between 4 and 5 percent of the total. Europe and Japan have no reason to dump the American Treasuries they hold, nor are they likely to stop buying them in the future. After all, U.S. monetary policy is no worse than what central bankers are doing to the euro and the yen. American dollars are still a satisfactory answer to currency diversification, and the relatively high interest rates on the treasuries may make them even more attractive.

China wants to prevent the dollar from weakening to keep its exports competitive.

Would Beijing sell the treasuries it holds to pressure the U.S.? Probably not, since doing so would not serve its global economic strategy. China wants to extend its network of regional trade agreements, exclude the West from promising markets and prevent the dollar from weakening so that Chinese exports remain competitive.

Over the past five years, Chinese authorities have stabilized the exchange rate at about 15 U.S. cents to the yuan. China has no interest in starting a war over treasuries. The damage such war could provoke is moderate, especially if the Fed reacted with more monetization. Moreover, selling treasuries and putting pressure on the dollar would lead to an appreciation of the yuan, which is not in Beijing’s interest.

The long run is different. If China wants to expand the role of the yuan as an international currency at the expense of the dollar, it might well decide to undermine the dollar’s reliability. But this does not seem likely to happen soon.

Scenarios

Although financial markets are global, Europe’s large and increasing government debts are a European problem. They are likely to stay that way as long as Frankfurt keeps a lid on interest rates, relies on monetization and nudges European financial institutions toward buying government bonds.

The picture could change if Brussels issues its own EU bonds, if it no longer finds buyers within the bloc, or if Frankfurt stops monetizing the debt and forces EU authorities to make economic or political concessions to persuade potential non-European creditors to intervene. This is unlikely.

As for the U.S., monetization has helped defuse the international repercussions of the rise in public debt, which is prominent in the portfolios of global investors and central bankers. Although the sustainability of U.S. public debt depends somewhat on decisions made in Beijing, the danger is limited, at least in the short term.

On one hand, although the Chinese do hold large amounts of treasuries, they are just a small fraction of the U.S. debt. Selling them would inflict relatively minor damage. Yet despite its profligacy, the Fed has failed to do whatever it takes to keep interest rates low, and has ensured that treasuries remain attractive, given the poor alternative – the euro.