Rare earth minerals return to the U.S. security agenda

China has recently hinted that it could use its stranglehold on the production and processing of rare earth minerals to strike at the U.S. economy. The Trump administration has put forth several initiatives for ending the U.S. reliance on China, but the effects will only come in the medium to long term.

In a nutshell

- Beijing has threatened to cut off rare earth supplies to the U.S.

- The U.S. is severely dependent on China for such resources

- The government is trying to build up a domestic supply chain

- That is a long-term project. There are few short-term solutions

At the end of May 2019, Beijing retaliated against American tariffs and trade restrictions by threatening to restrict Chinese exports of rare earth elements to the United States. The move highlighted U.S. dependence on rare earth imports from China, its most prominent geopolitical rival.

President Donald Trump’s administration has begun to address the vulnerabilities through several new initiatives. But new recommendations in its June 2019 federal strategy will only improve the U.S. supply security of rare earths and other critical minerals in the medium to long term.

Veiled threats

In May, the People’s Daily, the official newspaper of the Communist Party of China, warned the U.S. not to “underestimate China’s ability to strike back” against its tariffs, hinting that rare earths could be used as a “counter weapon” since the U.S. has an “uncomfortable” dependence on them. Chinese President Xi Jinping made a politically symbolic visit to one of the country’s main facilities for mining and processing rare earths, and Beijing imposed a tariff of 25 percent on rare earth imports from the U.S., targeting especially the Mountain Pass mine in California. The posturing recalled Deng Xiaoping’s warning in 1992: “The Middle East has its oil and China has rare earths.”

In the following weeks, prices of rare earth elements soared, as did those of shares in Chinese mining and refining companies – some as much as 150 percent. According to a recent Commerce Department report, the U.S. is import-reliant (defined as requiring imports to satisfy more than 50 percent of annual consumption) for 31 of the 35 minerals designated as critical by the government, including but not limited to rare earths. For 14 critical minerals, the U.S. does not have any domestic production and relies entirely on imports for its supplies. Highlighting this dependency, the Trump administration has exempted rare earths from its tariffs on Chinese imports.

Rare earths first began making geopolitical headlines in the autumn of 2010, when China suspended its supplies to Japan. As the world’s largest producer and exporter of rare earths, and home to 37 percent of global reserves, China was trying to use its de facto near-monopoly to gain leverage in an escalating diplomatic conflict over maritime territories and energy resources in the East China Sea.

Facts & figures

Increasing demand for rare earth elements

Since then, Japan, the U.S., the European Union and others have reviewed their strategies for obtaining such materials, seeking to diversify supply and reduce dependence on imports. A Congressional report warned in 2010 that despite having significant reserves of rare earths, the U.S. would need at least 15 years to break its dependence on Chinese exports due to the lack of mines and supply chains and scientific and engineering expertise.

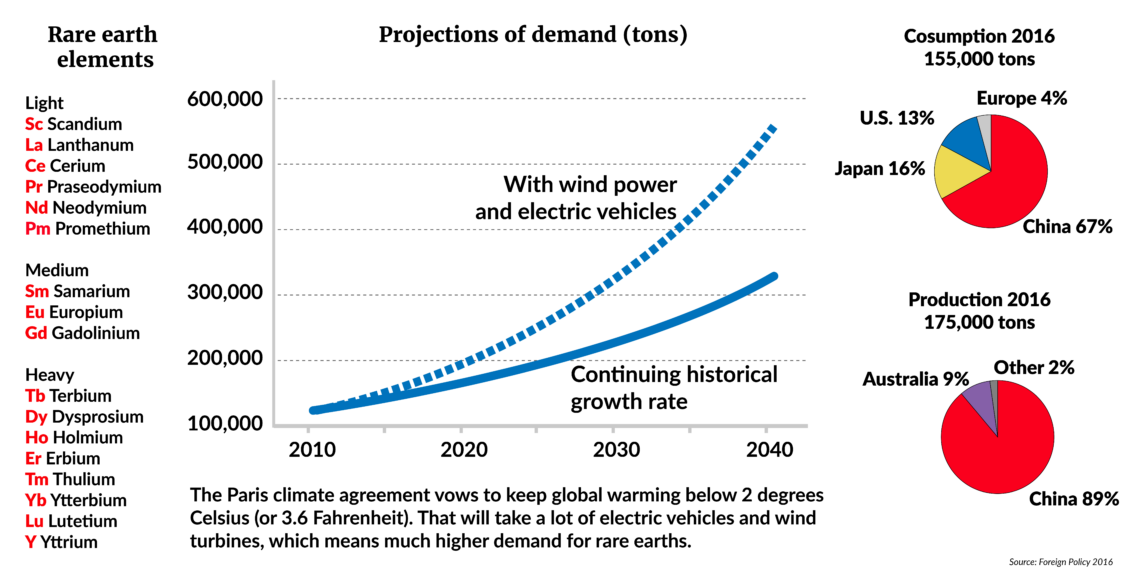

With a wide range of civilian and military applications, as well as the expansion of “green” and digital technologies, global consumption of rare earth elements is growing. Global production increased from 132,000 tons in 2017 to more than 170,000 tons in 2018.

The fate of the Mountain Pass rare earths mine in California (see fact box) is symptomatic of the ups and downs in attention rare earths receive from government and industry, as well as the lack of a long-term strategy for supply security.

Facts & figures

History of the U.S. Mountain Pass mine

- 1970-80s: The mine in California once produced 70 percent of the world’s rare earths supplies until the early 1980s. Until the mid-1980s, it provided 100 percent of the U.S. demand and simultaneously supplied 40 percent of global demand

- End of 1980s – early 2000s: Following a Chinese production increase and resulting price collapse, many rare earth mines in the U.S. and elsewhere in the West lost commercial profitability and were forced to close. By the early 2000s, most of America’s rare earth facilities had transferred their patents to China in exchange for access to its large rare earth reserves

- 2003: The Mountain Pass mine closes, ending U.S. rare earth production

- 2005: State-owned China National Offshore Oil Corporation offers $18.5 billion for U.S. oil company Unocal, which owned the mine at the time. The deal faced significant opposition in U.S Congress, and the offer was withdrawn. Chevron bought Unocal for $17.9 billion

- 2008: Molycorp buys the Mountain Pass mine from Chevron

- 2011: Molycorp restarts the mine by expanding its capacity for light rare earths. The production of heavy rare earths, considered particularly important for key technologies in military and civilian applications, remain produced exclusively in China

- 2015: Molycorp and its Mountain Pass mine go bankrupt

- 2017: The Molycorp-owned mine goes up for auction and is acquired by an American consortium with China’s Shenghe Resources holding a nonvoting minority interest in the company

- 2018: The Mountain Pass mine restarts production with an annual capacity of 15,000 tons

In this light, two scenarios for the following years are worth considering:

Ending U.S. reliance on China

The U.S. Department of Energy has already funded research for developing cost-effective methods of extracting rare earths from coal to guarantee domestic supply. Researchers at the University of Kentucky claimed to be able to provide a 98-percent pure concentrate of some rare earth elements from a coal source.

The U.S. dependence on China’s rare earth exports has also been a growing concern for U.S. legislators. In 2016, the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources supported a bill that called for creating a domestic rare-earths supply chain, but the bill failed to pass into law. Critics have argued that the Mountain Pass mine will not be economically competitive unless rare earth prices increase substantially.

In 2017, President Trump signed two rare earth-related executive orders. The first, Executive Order 13806, aimed at strengthening the U.S. industrial base, which had to cope with a decline of critical markets and suppliers, aggressive industrial policies of competitor nations (i.e. China) and the loss of vital skills in the domestic workforce. In December 2017, he signed Executive Order 13817 aimed at ensuring reliable supplies of critical minerals such as rare earths and battery metals (lithium, cobalt and others).

In June 2019, a new federal strategy on critical minerals was adopted.

Also in December 2017, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) published a list of 23 critical minerals, chosen due to their importance to the U.S. economy and the impact of potential supply restrictions. They are considered critical to a “broad range of existing and emerging technologies, renewable energy, and national security.”

Finally, in June 2019, a new U.S. “Federal Strategy to Ensure Secure a Reliable Supply of Critical Minerals” was adopted as a comprehensive interagency initiative. It presented six “Calls to Action,” 24 goals, and 61 recommendations for adaptive and coordinated efforts across the federal government and will be reevaluated every five years.

Facts & figures

The U.S. federal critical materials strategy:

Six calls to action

- Advance transformational research, development and deployment across critical mineral supply chains

- Strengthen U.S. critical mineral supply chains and defense industrial base

- Enhance international trade and cooperation related to critical minerals

- Improve Understanding of Domestic Critical Mineral Resources

- Improve access to domestic critical mineral resources on federal lands and reduce federal permitting time frames

- Grow the American critical minerals workforce

The strategy seeks to reduce U.S. vulnerabilities in the critical minerals supply chain by increasing domestic exploration, production, recycling and reprocessing, as well as with industry incentives and investments in research and development. The report highlights the need for developing cost-effective processing, separation and manufacturing capacities, without which economic and security risks will simply move down the supply chain. The U.S. has therefore intensified information sharing with allies like Australia, Canada and the United Kingdom on best practices in supply security strategies and mineral stockpiling.

However, identifying new domestic sources of critical materials will be an uphill battle. As the authors of the strategy write, USGS data shows that “less than 18 percent of the U.S. landmass has been geologically mapped at the necessary scale, and less than 5 percent of the nation has regional aeromagnetic datasets at the required resolution to perform robust mineral resource assessments.” Less than 35 percent of its exclusive economic zones has been mapped with modern methods to facilitate mineral assessments.

Furthermore, it remains questionable whether China would in fact implement its “nuclear option” for restricting its rare earths exports now, preferring to preserve this option for a potential war. Cutting off its supplies could speed up the development of production capabilities elsewhere. After the 2010 global supply shock, new mine production began in Australia (at Mount Weld) and in the U.S.

As a direct reaction to China’s recent supply threats, the Pentagon is now seeking new federal funding to bolster domestic production of rare earths. China accounted for 80 percent of U.S. rare earth imports between 2004 and 2017.

Facts & figures

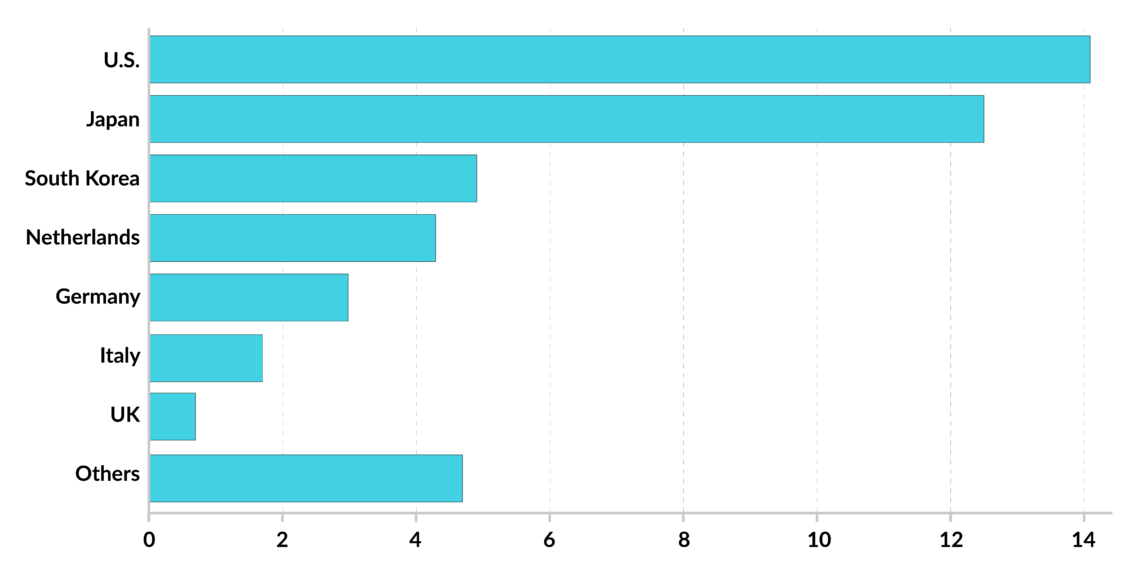

China's rare earth export destinations

Exports in thousand tons

An October 2018 Pentagon report highlighted the vulnerabilities in the U.S. defense industrial base and called for boosting production, processing and stockpiling of critical supplies, though the U.S. defense industry accounts for less than 5 percent of the global rare earth demand. While the Mountain Pass mine is still the only operating U.S. rare earth facility, the owner, MP Materials, plans to start its own processing operation by 2020, with a capacity of 5,000 tons annually. At least two other rare earths processing plants are under construction or in the planning stages and will only open in 2022 at the earliest. In the long term, such projects could break China’s control over the global rare earths supply chains, particularly of its worldwide monopoly on refining and reprocessing.

Facts & figures

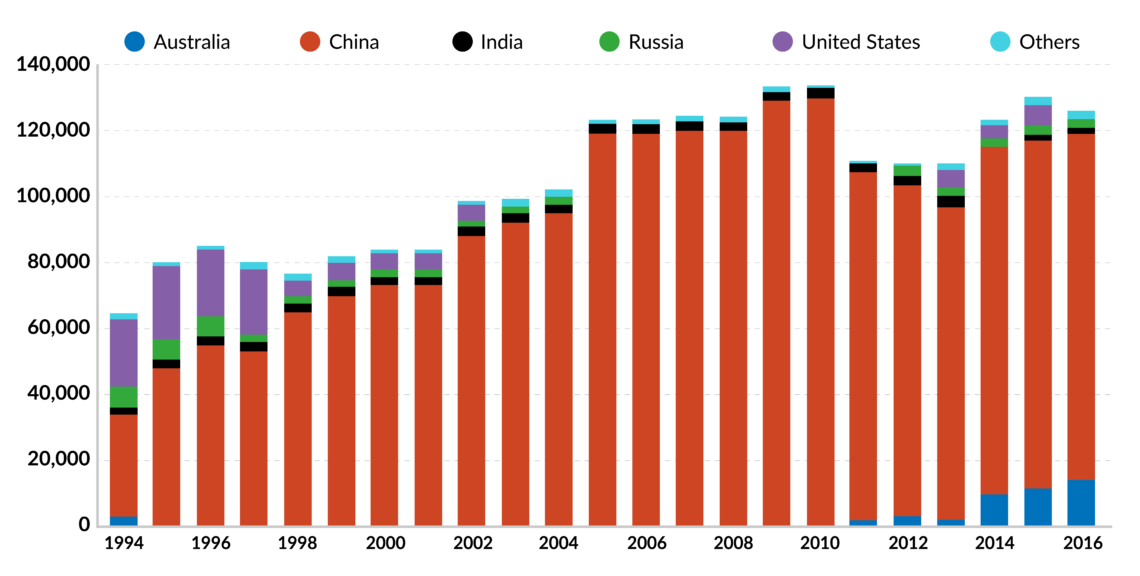

Rare earth element production

(metric tons - rare earth oxide equivalent)

Coping with supply security challenges

The Pentagon has long been concerned about the U.S. defense industry’s growing dependence on imports of rare earths and other critical materials from China.

Facts & figures

Examples of U.S. weaponry using rare earths

- Virginia-class nuclear-powered submarines each use 9,200 pounds of rare earths

- The Arleigh Burke-class guided missile destroyers require about 5,200 pounds (66 in service and 14 under construction or on order)

- The F-35 Joint Strike Fighters each use 920 pounds of rare earths (410 have been built and 2,456 aircraft will be built for the U.S. in total, while at least a further 731 could be built for other countries).

It has promoted finding substitutes, reclaiming waste through recycling and preparing contingency plans, including stockpiling, and has supported efforts to diversify imports. Overall, however, the Pentagon’s efforts have been limited. As prices of rare earths and other critical materials fell, so did U.S. attention to the issue.

Facts & figures

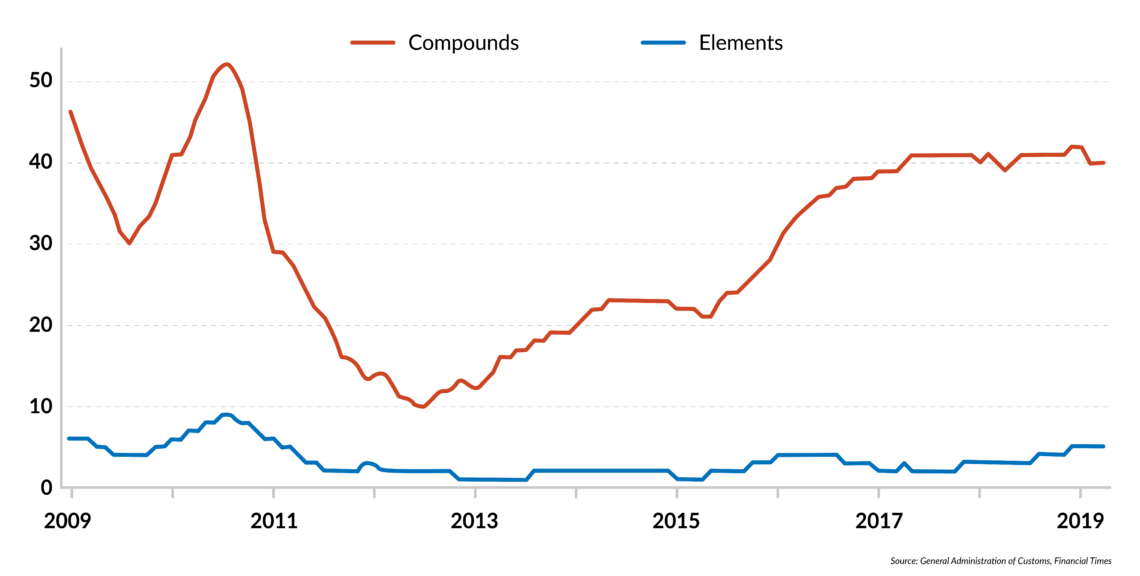

China's rare earth exports

Rolling 12-month total (thousand tons)

In 2018, the U.S. was still China’s largest rare earth export market. While China’s stranglehold on global production declined from 97 percent in 2010 to more than 80 percent in 2017 and even 71 percent in 2018, it has consolidated its monopoly on refining rare earths for products at the middle and end of the value chain, such as neodymium magnets, which are widely used in hard disk drives and a variety of conventional automotive subsystems such as power steering, electric windows, power seats and audio speakers. China has also strengthened its control over the global supply chain in recent years. Despite the renewed production of rare earths at the Mountain Pass mine in 2018, with an annual capacity of 15,000 tons, all of the rare earths produced in the U.S. needed to be shipped to China for processing and then reimported as refined or end products.

Facts & figures

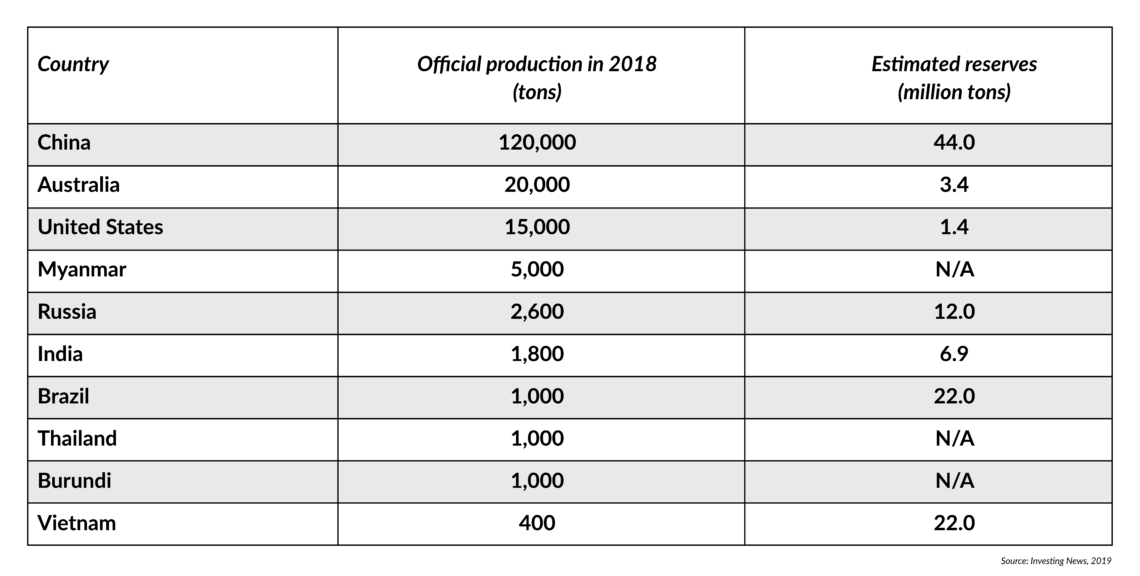

Top 10 rare earth producing countries and estimated reserves in 2018

Moreover, China’s official production data of 120,000 tons in 2018 (global production was 170,000 tons) does not include illegal mining. Its total production for the year has been estimated at as much as 180,000 tons. While Beijing has worked to curb illegal mining by closing thousands of small mines, it could start them up again if it feels the need to undermine the commerciality of international mines. China used this practice in the 1980s to acquire its production and export monopoly.

While U.S. government agencies are already working toward completing many of the goals identified in the June 2019 federal strategy, many proposed measures – such as recycling, reuse, finding substitutes and opening new mines – can take years to accomplish or face constraints in their implementation.

Scenarios

While the Trump administration’s efforts may significantly enhance the security of the supply of rare earths and other critical materials to the U.S., longer-term challenges will remain on the political agenda of future U.S. governments. And while options remain to address them, there are precious few short-term solutions to the rising dependence on critical materials imports from China. A reliable, steady supply chain for refined and processed rare earths could take as long as 20 years to build.

China’s global production and export monopoly, particularly of the “heavy” rare earths, as well as its refining and reprocessing capabilities, will remain a major challenge not only for the U.S. but also for Japan and the EU. The future belongs to those powers that not only become technology leaders but which can also secure the increasingly important supply of rare earths and other critical materials for their future disruptive technologies.