Uncontrolled immigration damages the Danish welfare system

During the European migrant crisis, Denmark – wedged in between morals-driven neighbors – made it clear that refugees were not welcome. This serves as a reminder of how moralizing politics can obscure the interplay between migration and a sustainable welfare state.

In a nutshell

- Pragmatic Denmark weighs integration prospects of aliens

- Immigrants of some backgrounds are less likely to assimilate

- Danish political elites respond to citizens’ concerns

At the peak of the European migrant crisis, Germany and Sweden took the moral lead in welcoming refugees. German Chancellor Angela Merkel will be long remembered for her claim that Wir schaffen es, “We will manage it.” In Sweden, Prime Minister Stefan Lofven took a similar stand, proudly proclaiming that “Our country does not build walls.” In 2015, while Germany took in one million asylum seekers, Sweden (with a tenth of the German population) took in 165,000.

Meanwhile, wedged in between its two morals-driven neighbors, Denmark made it abundantly clear that refugees were not welcome. As the trek of migrants reached its border with Germany, the government adopted a wave-through policy. Police formed cordons along the road leading to Sweden, where welcoming committees stood ready.

The Danish example may serve as a crucial reminder to other European nations of how moralizing politics can obscure the vital interplay between migration and a sustainable welfare state.

The crackdown

Having come to power in June 2015, the center-right government of Lars Lokke Rasmussen (2015-2019) made a point of introducing the strictest immigration rules in Europe. In January 2016, it made waves by adopting a new law allowing police to search asylum seekers for cash and valuables that could be confiscated to defray the costs of processing their applications.

A new law required immigrants to shake hands with a state official during the citizenship pledge ceremony.

Some of the ensuing legislation was general. Temporary residence permits were to be issued for one or two years only and could be revoked in several situations. Family reunification applications for partners under 24 years of age were to be refused.

Other regulations were aimed at Muslims. They included a ban on wearing face coverings, like a burqa or a niqab, in public places. A new law required immigrants to shake hands with a state official during the citizenship pledge ceremony, regardless of religious belief regarding physical contact with the opposite sex.

A fundamental milestone was marked with the 2017 “ghetto law.” Aimed at eradicating lawlessness in neighborhoods dominated by the Muslim population, the legislation called on public housing corporations to sell off some apartments to wealthier newcomers and envisioned that some unredeemable parts would be demolished. Children living in the “ghettos” would be required to attend at least 25 hours of classes per week to learn Danish values. (Very small children, from age one, in troubled neighborhoods would be forced away from their parents and placed in mandatory day care centers to be inculcated with Danish values. The idea is to eradicate ghettos both physically and mentally.) Asylum seekers insisting on remaining in such “ghettos” would have their benefits reduced. Crimes committed there would earn double penalties and special “visitation zones,” where police can stop and search at will, were established.

In December 2018, the Danish government approved the introduction of a restrictive facility to house asylum seekers that have committed crimes but cannot be deported. Located on the remote Lindholm Island, with no permanent inhabitants, the facility would house some 100 people.

In February 2019, a new immigration law stated that refugees must be deported back to their home countries as soon as it is legal to do so.

Driving the message home, Danish Minister for Immigration, Integration and Housing Inger Stojberg (2015-2019) had a counter installed on the ministry website tracking the number of laws passed to restrict migration. When it reached 50, she posted a picture on social media that showed her serving cake to celebrate. She also published a comment claiming that Muslim bus drivers and hospital workers fasting during Ramadan pose a safety risk to the community.

It is not surprising that Denmark has attracted much venom from circles advocating liberal migration policies.

Ms. Stojberg made no secret of the fact that her iPad has a screensaver showing the cartoons of Prophet Muhammad that caused massive outrage among Muslims when published by the leading Danish daily Jyllands-Posten in 2005. Also, after parliament passed the Lindholm Island project, she noted that “They are unwanted in Denmark. And they will feel like that.”

Change of tide

The combination of stricter legislation and public officials signaling that migrants from Muslim countries were not welcome in Denmark has had an impact. In 1997, half of all immigrants seeking asylum and family reunion were from non-Nordic countries. In 2017, some 65 percent of new residents were international students and labor migrants, with family reunification cases making up only 13 percent. One year later, refugees accounted for only two percent of all foreigners granted residence permits.

All told, it is not surprising that Denmark has attracted much venom from circles advocating liberal migration policies. The main problem with accusations of racism and xenophobia is that they do not take into account Denmark’s track record of both tolerance and liberalism – values that, arguably, have sunk deeper roots in that country than nearly anywhere else. Denmark routinely scores at the very top of international prestige rankings. It is both one of the least corrupt nations in the world and the United Nations leader in sustainable development indicators.

The easy-going nature of Danish society is distinctly reflected in its reluctance to intervene in how people live their lives. Denmark belatedly and reluctantly introduced bans on smoking. Alcoholic drinks are sold in supermarkets. Prostitution is legal. In Copenhagen’s Christiania “free zone,” soft drugs like cannabis are sold freely. Denmark was among the pioneers in championing LGBT rights and the first nation to legalize same-sex marriage. In stark contrast to stadium-goers in other European countries, Danish football fans are known as “rooligans” – a wordplay on the Danish world rolig, which translates as “peaceful.”

Is it possible that what is perhaps the most tolerant society in the world could have suddenly become a hotbed for racist and xenophobic mobilization? Or is there another explanation?

The Danes’ motives

One of the main reasons why so many Danes routinely tell pollsters that their country is a great place to live is clearly linked to the achievements of their welfare state. In addition to having the lowest poverty rate in the world, Denmark offers its citizens free healthcare, excellent childcare, generous parental leave, free higher education and much more. What makes the question of immigration so controversial for the citizens is their belief that the very expensive and generous Danish welfare state cannot coexist with open borders.

Experience shows that the prospects for integration tend to hinge on what part of the world the migrants come from.

Nobel Prize-winning American economist Milton Friedman put it simply: “It’s just obvious you can’t have free immigration and a welfare state.” The legitimacy of high taxation that is needed to support generous welfare benefits requires all participants to share the fundamental values of solidarity that preclude freeloading and stigmatize living on welfare if it can be at all avoided.

The problem that looms so large in present-day Europe is that immigration activists appeal not to economic common sense but moral sensitivities. They claim that compassion requires generous migration policies, irrespective of the cost. Indeed, merely suggesting that there may be an upper limit to the number of migrants that can be integrated is routinely branded as racism.

Experience shows that the prospects for successful integration tend to hinge on what region in the world the migrants come from. As long as migrants arrived from countries with social and cultural norms similar to Denmark’s, its citizens and leaders maintained a welcoming attitude. Immigrants joined the labor force and there were few cultural clashes.

The first harbinger of trouble to come arrived with the attacks by the Islamist terror group al-Qaeda against the United States in 2001. Then came the outrage surrounding the publication of the Muhammad cartoons. The violent response to the 2005 publication of such cartoons by the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten served to galvanize many Danes against Islam, and thus to pave the way for draconian measures against Muslim immigrants in particular. In 2010, Denmark began tightening its laws on immigration.

Social welfare for asylum seekers was reduced, as was the duration of temporary residence permits. The “hold period” before family unification could begin was extended from one to three years. Subsequent studies have shown that concerns over the integration prospects of new categories of immigrants were well-founded.

Question of values

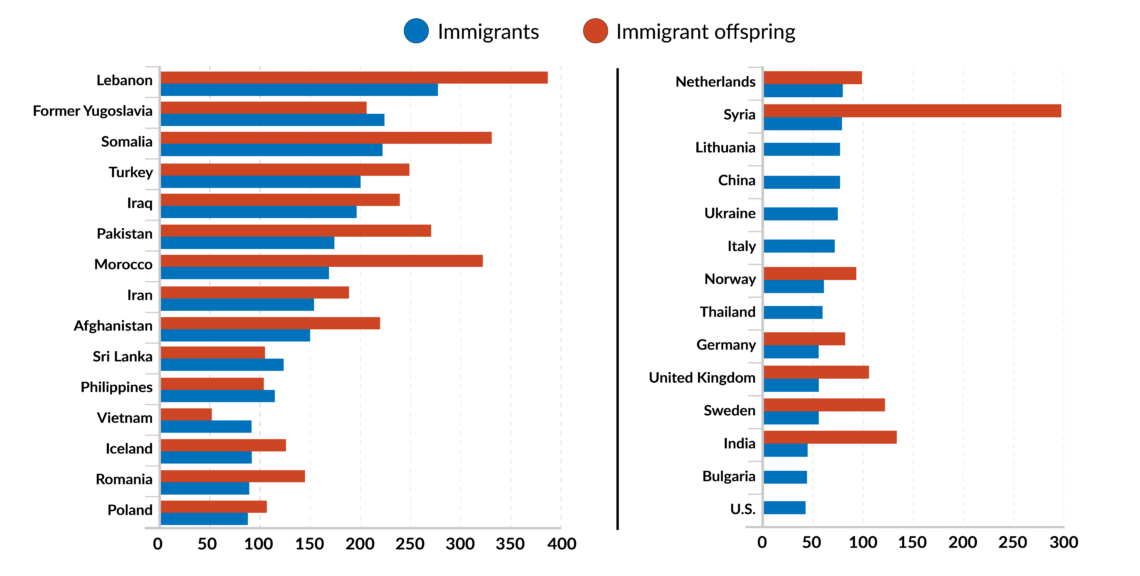

According to a 2015 study by the OECD, 20 percent of native-born adult children of immigrants in Denmark were not in education, employment or training. In a 2017 study, the ministry of finance contradicted the claim that immigration was an economic boon to the country. Official data showed that the newcomers and their descendants generated a sizeable net loss to the state coffers. While 80 percent of Danes held a job, the number for non-Western people was only 56 percent.

In the run-up to the June 2019 national election, parties on the right campaigned for even stricter rules on immigration and Islam. Having long been a champion of restrictive migration rules, the Danish People’s Party (“Dansk Folkeparti”) demanded a total halt to asylum, irrespective of what international conventions the country may have signed.

The party ran on a platform that combined restrictive migration policies with a renewed wager on the welfare state.

In this ambition, it was upstaged by the newly formed party Hard Line (“Stram Kurs”), whose founder, Rasmus Paludan, called for a total ban on Islam and for all Muslims to be deported. His campaign antics entailed public burnings of the Koran – wrapped in bacon – that caused rioting in predominantly Muslim neighborhoods.

The outcome of the election was surprising. In 2015, the once-reviled Danish People’s Party had won 21.1 percent of the vote, making it the second-largest party after the Social Democrats. Its leader and co-founder, Pia Kjaersgaard, was elected speaker of parliament. In stark contrast to the German and Swedish practice of ostracism, Danish politics embraced public discontent and prioritized changes to migration policy.

Political outcome

The main lesson of the 2019 election was that the space for single-issue anti-migrant policies has been reduced sharply. In 2019, the Danish People’s Party received no more than 8.7 percent of the votes and Mr. Paludan’s Hard Line failed to clear the two-percent threshold for representation in parliament.

The Social Democrats were the winners. Faced with the prospect of losing yet another election on migration-related issues, the party decided to run on a platform that combined restrictive migration policies with a renewed wager on the welfare state. Aged 41, the party leader, Mette Fredriksen, became the country’s youngest prime minister and its second female leader.

Having won the election, she angered the opposition by agreeing with parties on the left to backtrack on some of her migration promises. The concessions, however, were minor. She accepted scrapping the Lindholm Island project but vowed to maintain the focus on repatriation and temporary asylum. It also bears noting that the new prime minister had supported both the “jewelry bill” and the burqa ban.

The emergence of parallel societies ruled by incompatible values serves to drive a wedge deep into the very fabric of society.

While the Danish People’s Party has lost a critical election and could be facing marginalization, its program on migration has won. With all the major political parties in agreement, the extremes on the left and right have been marginalized. Danish politics may again focus on what Denmark does best – namely, working diligently on providing welfare for its citizens.

For Denmark’s next-door neighbors, there are valuable lessons to be learned here. German politics has been concentrated on keeping the Alternative for Germany (AfD) out of power, and Swedish politics has an obsession with isolating the Sweden Democrats. The result in both cases has been to boost electoral support for the targeted organizations.

Ostracism and condemnations may provide activists with a warm glow of moral superiority, however, given the genuine problems posed by migration, it is not a winning strategy. All it does is ensure that immigration remains a hot-button issue. This polarizes society, boosts support for political forces with an anti-migrant agenda and crowds out efforts to deal with problems such as jobs, welfare and security on the streets, which are the primary concerns of most voters.

Scenarios

Looking forward, Denmark may serve as a litmus test for the future of liberal politics in Europe.

Continued emphasis on welfare state

In one direction lies continued emphasis on the welfare state, combined with tight restrictions on who will be allowed access to these benefits. It entails a shift of focus from immigration to integration and swift deportation of those who do not qualify for inclusion. While such policies will be conducive to political stability and enhanced prosperity for the resident population, they will also provoke moral outrage over the exclusion of the needy and poor that have not had the fortune of being born in Denmark.

Next migrant wave

In the likely scenario of a renewed wave of migrants entering Europe from the south, Danish mainstream political parties will come under heavy pressure from European Union states to revise their hardline stance. The issues encountered by Sweden, where newcomers are allowed instant and full access to social welfare, may fortify Denmark’s resolve to defend its policies.

Emergence of class society

The escalating costs of supporting immigrants that cannot and will not be integrated are eroding the bedrock of the welfare state. The emergence of parallel societies ruled by incompatible values serves to fuel gangland violence and drive a wedge deep into the very fabric of society. The growing number of undocumented aliens suggests the emergence of a harsh class society, where aliens are ruthlessly exploited and where wages in some kinds of work are depressed.

It is symptomatic that Denmark recently decided to introduce border controls against Sweden. This, however, will not address the fundamental challenge that will determine the future of the nation-state as such. Does a Somali peasant have the same rights to welfare benefits as a Danish metal worker who has put in four decades of hard labor? Sweden says yes. Denmark begs to differ.