Kosovo and Serbia: An incomplete peace

The toughest nut to crack in the Balkans remains the resolution of the Kosovo-Serbia conflict. Recently, the U.S. has stepped further into the fray, jockeying with the EU for primacy in leading the negotiations. At the same time, the regime in Belgrade has strengthened.

In a nutshell

- The EU and U.S. are tussling over leading peace talks

- Kosovo’s wobbly government is under pressure

- A resolution of the conflict could depend on the U.S. election

Talks of a resolution of the Kosovo-Serbia conflict on a potential final peace agreement remains the hottest geopolitical issue in the Western Balkans. After two years of war and two decades of incomplete peace, it remains unclear if, when and how an agreement between the two sides can be reached.

In 2010, the International Court of Justice ruled that Kosovo had not violated international law when it declared independence from Serbia two years earlier. Based on that decision, the United Nations put the European Union in charge of normalizing relations between the two states. This was supposed to occur through a process dubbed the Brussels Dialogue.

After eight years of negotiations (2011-2018), there were 33 agreements signed on the matter, but none were fully implemented. Kosovo and Serbia remain formally at war: there is no conflict resolution, no peace accord, no reconciliation process, no mutual recognition, no established full diplomatic relations and no border demarcation.

Facts & figures

Territory and trade

The Brussels Dialogue began as talks on technical issues and later developed into political negotiations. They stopped two years ago when Serbia began pushing for a land swap and Kosovo responded with tariffs on Serbian goods.

After this hiatus, the United States began pushing for a peace deal. The two sides were due to meet for talks on June 27, 2020, at the White House. After the meeting was announced, the EU declared it would restart the Brussels Dialogue on June 25. President Macron called for talks in Paris on July 17. The planned White House meeting was canceled after Kosovan President Hashim Thaci was indicted on war crimes charges by prosecutors in the Kosovo Specialist Chambers in the Hague.

The U.S. and the EU have taken disparate approaches to the talks.

The U.S. intended to restart the process through “economic cooperation” that would end with a binding bilateral agreement on mutual state recognition. Yet that final outcome seems impossible as long as Serbia remains averse to recognizing the Republic of Kosovo. Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic has offered many reasons for his resistance. Recently, he has used the justification that the EU does not expect his country to recognize Kosovo’s independence. Instead, Brussels only wants Belgrade to refrain from blocking Kosovo’s UN membership.

The U.S. and the EU have taken disparate approaches to the talks. Washington initially mentioned the goal was mutual recognition and a path toward EU accession for both. Until mid-June 2020, there was a perception that the U.S. supported any accord agreed upon between the two countries that would achieve these goals – including one that included a land swap.

However, Richard Grenell, President Donald Trump’s envoy for the negotiations, denied that was the official position and contended the redrawing of borders was an idea put forward by former National Security Advisor John Bolton. Mr. Bolton has refuted that assertion, saying Presidents Thaci and Vucic had tabled the idea themselves.

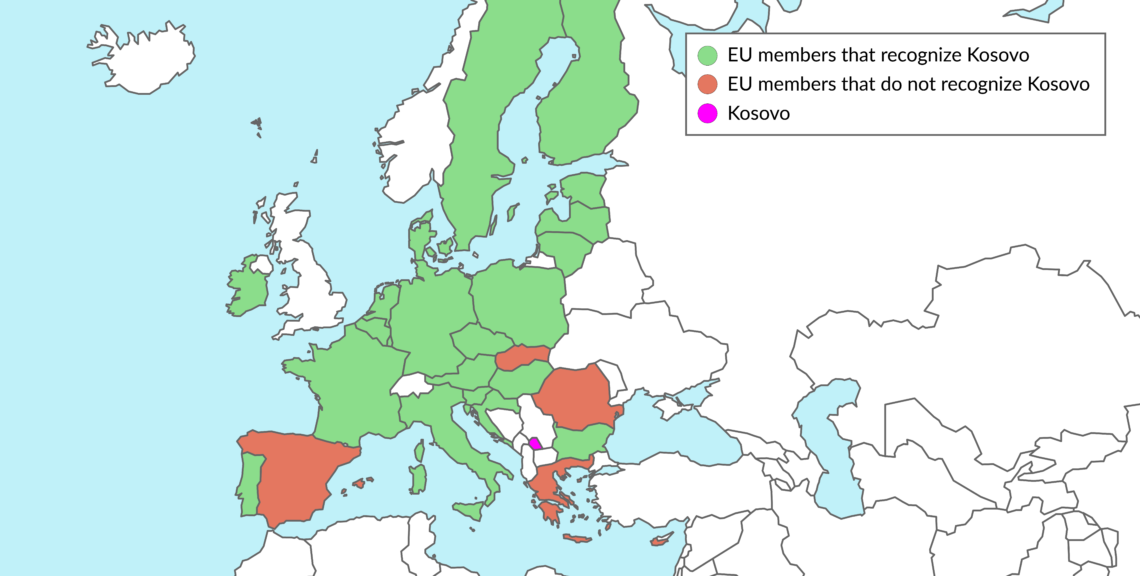

EU envoy Miroslav Lajcak, from Slovakia, was more careful, avoiding any reference to a land swap and mutual recognition. He and his boss, High Representative of the European Union Josep Borrell of Spain, hail from two of the five EU member states that have not yet recognized the Republic of Kosovo. Having these two men in charge of the EU’s Kosovo policy put the credibility of their mediation in question.

After meeting with Mr. Lajcak in Belgrade on June 22, President Vucic declared that he respected Mr. Grenell’s attempts to move things along, but that the dialogue with Kosovo should be mediated by the EU.

While the EU and U.S. squabbled over how best to move the dialogue forward and which would take the lead, Russia’s position remains consistent. In a June 18 meeting in Belgrade with President Vucic, Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs Sergei Lavrov repeated Moscow’s view that any resolution to the Kosovo-Serbia conflict would have to be approved by the UN Security Council.

On June 23, Serbian President Vucic met Russian President Vladimir Putin in Moscow. His visit to the Kremlin took place four days before the expected meeting at the White House, and two days before his visit to Brussels. The message was clear: before talks with the U.S. and EU, President Vucic went to Moscow for instructions.

To facilitate the talks at the White House, Kosovo ended trade tariffs and what were termed “reciprocal measures” against Serbia, stopped applications for membership in Interpol and UNESCO, and allowed Serbian elections to go forward in Kosovo (which were certain to pad the victory of Mr. Vucic’s party). Serbia’s only concession was to promise to stop campaigning against recognition of Kosovo. Belgrade quickly broke this promise, however, when Serbian Minister of Foreign Affairs Ivica Dacic made official statements thanking Algeria and Mexico for their “principled stance” in not recognizing Kosovo.

Hopes for speedy negotiations toward a deal were dashed after the Hague’s special prosecutor brought its war crimes indictment against President Thaci. The leader of the Democratic Party of Kosovo (PDK) was also indicted on war crimes charges. A special pretrial judge is set to review the indictment and rule on whether to confirm the indictments by October 24, 2020. Until then, it will hamper Pristina’s position in talks with Belgrade.

On July 10, EU officials hosted a video conference between President Vucic and Kosovo’s Prime Minister Avdullah Hoti. The two met face-to-face in Brussels on July 17. Neither meeting yielded results.

Three governments

The domestic political environments in Serbia and Kosovo are vastly different. Kosovo has had three governments in less than a year, due to international pressure that it be more flexible and cooperative in the negotiations with Serbia. Last summer, the government of Prime Minister Ramush Haradinaj resigned. Ostensibly, this was because Mr. Haradinaj was due to be questioned by the Special Prosecutor’s Office in the Hague. Unofficially, he resigned due to Washington’s disapproval of his refusal to abolish the trade tariffs against Serbia.

On February 3, Albin Kurti took over as prime minister. By March 25, parliament passed a vote of no confidence in his administration, again over strained relations with the U.S. and stalled negotiations with Serbia. On June 3, the government of Prime Minister Avdullah Hoti took over. Its legitimacy hangs by a thread – it won power by a single vote in parliament (61 out of 120 representatives), and without a national election, due to a controversial decision by the constitutional court. The survival of the government depends on several coalition partners, especially the 10 votes of the Serb List (Srpska lista), which is heavily influenced by Mr. Vucic.

Moreover, the proceedings at the Specialist Chambers will cast a shadow over the government. The Hoti administration’s most vocal supporter is President Thaci. If his indictment is confirmed, it will further undermine its position.

No change in Serbia

In contrast to Kosovo, those pulling on the levers of power in Serbia remain in place. In the June 21 elections, President Vucic’s party won 63 percent of the vote, giving it 158 seats in the 250-seat National Assembly. Its junior coalition partner won 11 percent of the vote, meaning that the government now has the two-thirds majority necessary to approve any deal with Kosovo. The main opposition coalition, Alliance for Serbia, boycotted the election, resulting in the country’s lowest-ever turnout for parliamentary elections. Neither the EU nor the U.S. voiced any objection to the validity of the vote.

President Vucic enters this phase of the dialogue with the upper hand.

President Vucic now has a stable majority and the political capital he needs to finalize talks with Kosovo. He enters this phase of the dialogue with the upper hand. In Kosovo, the prime minister (with a formal but unstable grip on power) and the president (who holds the real power but has been indicted for war crimes) continue to jockey for primacy. The most likely outcome is that Prime Minister Hoti, with his fragile majority, will take the lead in the talks. He may ask the opposition PDK party to join in a unity government to shore up his position.

In contrast to Serbia, there is no political party in Kosovo’s parliament with a majority of votes. In fact, the opposition is particularly strong. The Levizja Vetevendosje (Self-determination Movement, LVV) and the PDK party together have 54 votes. Even a small shake-up in loyalties could turn the tables.

Wider consequences

Within the region, talk of the land swap has increased fears that other such deals might be sought. North Macedonian President Stevo Pendarovski has warned of a possible domino effect and has asked for international guarantees against such an outcome.

So far, the U.S. and Europe have preferred stability to democracy, and have been willing to put up with corruption. If the West continues to take this approach, it will lose the trust of people in the Western Balkans, who will see its demagogic lectures on the rule of law, anti-corruption measures and the fight against organized crime as hypocritical. This tolerance for kleptocracy will push the Western Balkans away from the Euroatlantic community. Unfortunately, the region’s history shows how often such lofty values are sacrificed to achieve other interests.

Scenarios

Globally, any unfinished Kosovo-Serbia peace process will destabilize the transatlantic partnership, with Washington, Berlin, Paris and the European Commission all potentially taking different approaches. Washington and Brussels will tussle for primacy in mediation, while Russia will insist on inclusion.

It is likely that ahead of the November elections, if President Trump is looking for a quick foreign policy win, he may push for a resumption of talks between Pristina and Belgrade. However, at that time Germany will still hold the rotating EU presidency, and Chancellor Angela Merkel’s government will hold the line for a solution without border changes.

Berlin will probably push for a restart of talks in Paris. If President Trump is re-elected, however, Washington is likely to take over the peace process and try for a Camp David-style negotiation. If Mr. Biden is elected, the outcome will be the result of a U.S.-EU partnership.

Regardless, Moscow is unlikely to change its stance that the Security Council must approve any final deal. This will constitute the trickiest part of unraveling the Balkans’ last Gordian knot: the U.S. trying to avoid a showdown at the UN, and Russia trying to ensure it. If President Trump is reelected, there will likely be a diplomatic trade-off between the West and Moscow, possibly including a situation in which the Kremlin approves a Kosovo deal if the U.S. recognizes Russia’s annexation of Crimea. If Mr. Biden wins, the U.S.-Russia bargaining at the UN will drag on, with little prospect for compromise.

Locally, the victory of President Vucic’s party will strengthen his position in negotiations, and will also have a destabilizing effect on Kosovo’s political scene. It is less likely that the current government of Kosovo will survive in the long term, especially without the support of the PDK. With the government so wobbly and President Thaci’s indictment further destabilizing it, Kosovo will probably have to hold new elections by the end of the year. That will postpone the dialogue with Serbia for at least a half year, pushing back substantive talks until possibly the first half of 2022.

Any deal will have regional repercussions as well. The best outcome for stability in the Western Balkans would be an agreement that includes mutual recognition under the existing borders. Any other result could be taken as a precedent for similar changes. If the resolution deal of the Kosovo-Serbia conflict ends with an exchange of territory, how could such an outcome be prevented in Bosnia and Herzegovina or North Macedonia? After all, if a Serbian minority of just 5 percent warrants a land swap in Kosovo, would not the 25 percent of Albanians in North Macedonia also be justified in calling for a similar solution?

Considering such negative effects, an exchange of territory based on ethnicity would be a dangerous scenario that threatens peace and stability in the Western Balkans.