Revolution leaves Myanmar up for grabs

Myanmar’s 2021 coup looks to have backfired spectacularly. A determined youth resistance is fighting tooth and nail against military dictatorship – and winning.

In a nutshell

- The self-styled “revolution” in Myanmar is defying expectations, and may prevail over the military junta

- Local youth are fighting back and overwhelming the battle-hardened army

- Myanmar’s stability is one rare issue the U.S. and China can agree on

When Myanmar’s military coup took place on February 1, 2021, few thought it would turn out this way. Rarely has a military in Southeast Asia staged a successful coup and then failed to consolidate power afterwards. Yet this is precisely what is happening in Myanmar, the predominantly Buddhist nation also known as Burma.

A fierce and determined coalition of resistance forces are in the process of prevailing over Myanmar’s battle-hardened army. Although there have been failed coups in Southeast Asia – in the Philippines and Thailand in the 1980s and Cambodia in 1997 – once a putsch is successfully executed, there is usually no looking back. Indonesia’s coup in 1965 and the 13 successful military seizures of power in Thailand since 1932 fall in this category, with juntas holding on to power post-coup. Yet Myanmar is proving to be an extraordinary exception.

After nearly 50 years of military dictatorship since 1962, and a decade of political liberalization, economic reform and development progress between 2011 and 2021, the people of Myanmar have put their lives on the line for a future no longer ruled under the generals’ boots. In reaction to the 2021 coup, led by Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, a combined force of local youths, ethnic armies, civilian leaders and a defiant population have fought back in a deadly civil war to regain the democratic system that underpinned a better and more promising future. Scoring a growing number of battlefield victories in recent months, the resistance forces behind what they now call a “revolution” have turned the tide in the civil war.

Challenges to building a cohesive state

As Myanmar’s military dictatorship now appears untenable, the country’s future will soon hang in the balance. To secure a democratic future, the country needs a stakeholder dialogue at home and engagement from the international community and regional players, particularly the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, or ASEAN. Defeating the military is one thing, but putting together a viable pluralistic state with popular legitimacy in an ethnically fractious nation – an aspiring “federal democratic union” – will prove difficult and existentially daunting.

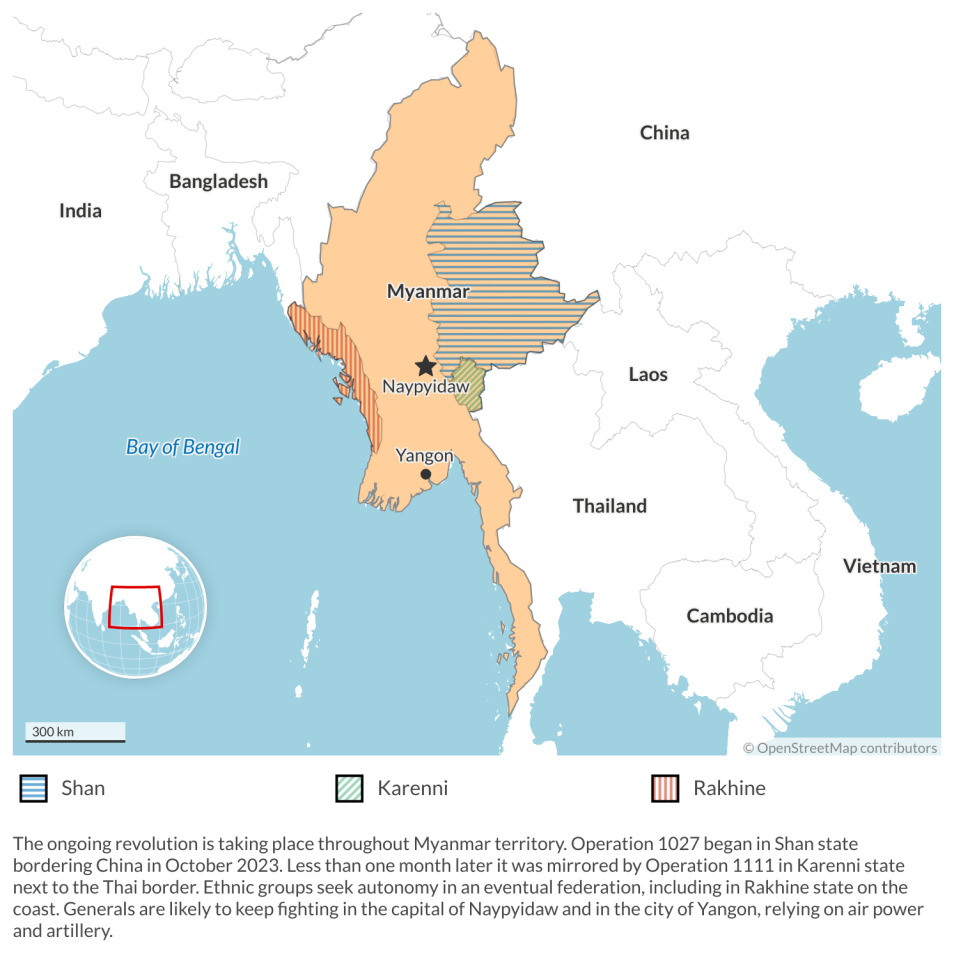

Myanmar’s grinding and virulent internal conflict could also drag on for more months as the generals hold out in major towns, such as the capital of Naypyidaw and Yangon, relying on air power, armor and artillery to last as long as they can.

But the numbers are stacked against the junta, the self-styled State Administration Council (SAC). Once a formidable 500,000-strong armed force, Myanmar’s military today is estimated at around 150,000 or fewer, overstretched across towns and regions in the country of 55 million people. Three-fifths of the population are Burmese, the rest myriad ethnic minorities led by the Shans and the Karens. Widely known as one of the most battle-tested militaries in the world for having fought countless conflicts over the decades against ethnic armies resisting central authority and seeking autonomy, the country’s military picked the wrong fight this time.

Motivation and resistance

Following the coup, Myanmar soldiers turned their guns on their own people in a murderous campaign to subdue anti-military street demonstrations initially led by the Civil Disobedience Movement. As troops killed hundreds of ordinary Burmese indiscriminately in subsequent weeks, popular anger boiled up. The catalyst was Myanmar’s youth in towns across the country, who rose up and fought back. Unlike their forebears, who tolerated half a century of military rule, the country’s teenagers and 20-somethings of today grew up during a decade of openness and possibilities, with improved standards of living and rising expectations.

Organized into People’s Defense Force (PDF) units nationwide, these brave youths first took up homemade arms and whatever rudimentary weapons they could muster to fight back against soldiers, stealing small weapons in the process. They later lined up with and received arms and training from the ethnic armies, formally known as the Ethnic Armed Organizations (EAO). The EAOs and PDF squads operate in coordination with the umbrella civilian-led National Unity Government (NUG). Using guerrilla tactics as well as conventional warfare, the resistance forces have taken the military to task and achieved at least a stalemate on the battlefields.

Facts & figures

Support for the resistance grew as military brutality and outright barbarism provoked a popular revolt, whereby the vast majority of the population, regardless of ethnic backgrounds, turned against the ruling generals. More recently, after being attacked left and right, up and down the country, the military lacked recruits, reinforcements and supplies, and faced deteriorating morale. It was a matter of time until it would reach a point of no return.

That point came late last year with “Operation 1027” under the so-called “Three Brotherhood Alliance” consisting of the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army, Ta’ang National Liberation Army and Arakan Army. Their coordinated offensive in northern Shan state bordering China succeeded in seizing two dozen towns and hundreds of military outposts, assisted by other EAOs and resistance columns in the Myanmar heartland. The October 27 operation was a breakthrough in self-belief and battlefield reality.

In addition to the resistance’s offensive in Shan state, anti-junta forces in Karenni state next to the Thai border in November won similar battles in a campaign known as “Operation 1111.” However the military tries to fight back, it appears the junta will not be able to prevail. The resistance forces are poised for an eventual triumph despite the military’s mobilization campaign through a new conscription law and recourse to air power.

After revolution, much remains to be done

Although the resistance is likely to win its revolution by overthrowing the military dictatorship, it still has a long way to go. The EAOs are motley and traditional adversaries among themselves and against central authority, while the PDF youths lack experience in shaping what comes next. Meanwhile, the NUG remains inchoate and devoid of clear and convincing leadership.

One half of the fight is to kick out Gen. Min Aung Hlaing, his cohorts and SAC cronies. The other and more important half is to convert and build the revolution into a workable compromise system of governance. The goal would be power-sharing in the spirit of the 2011-21 period that was led by the reform-minded Gen. Thein Sein and the democracy icon – though politically spent – Aung San Suu Kyi.

Ultimately what can emerge is a fractured but still intact country with a reduced central government and autonomous statelets, such as Rakhine, Shan and Karen, which may agree at most to a confederation arrangement.

Winning the civil war but letting the peace degenerate into renewed ethnic conflicts, unfulfilled expectations and a potential breakup of Myanmar into autonomous statelets harboring drugs and crimes would be detrimental not just for the local population but also to the regional neighborhood and international community.

To date, ASEAN has been ineffectual and divided over Myanmar, but it now has a second chance to get on the right track by engaging the NUG, EAOs and even military elements beyond Gen Min Aung Hlaing and the SAC. Thailand, under the newly elected government of Prime Minister Srettha Thavisin, is intent on playing a leading regional role and has begun to engage all major stakeholders.

What’s happened to Myanmar’s coup and autocratic rule is instructive. Myanmar is a case not of democratic rollback but of autocratic reversal, and it stands out for its aspirants of liberty putting down an autocratic imposition by force.

This does not mean, however, that the country by default will recover and proceed into a vibrant democracy of any sort. The decade of freedom and self-determination that earlier prevailed was, in fact, fragile, precarious and contingent on a civil-military compromise. Moving forward, compromises will be the key to Myanmar’s future cohesiveness and viability.

Scenarios

Possible: Country fractures following the revolution

There are multiple worst-case types of scenarios for Myanmar, and all are possible. One is that once the SAC junta collapses or when Gen. Min Aung Hlaing is ousted – whichever comes first – the resistance forces will turn on themselves. There is longstanding animosity and mistrust between the EAOs and the majority Burmese, who have been running the central government since postwar independence.

The EAOs could carve out smaller autonomous states of their own with disregard for any central government. Another undesirable outcome would be the emergence of fresh internal conflicts among the EAOs themselves, or between some of the EAOs and what’s left of the military.

Yet still another possible worst case would be an NUG aligned with PDF fighters battling some of the ethnic armies for control of the country. In short, the country we used to know prior to the coup will never be the same again.

Possible: International community mediates to keep the country whole and centralized

The best outcome would be a negotiated settlement among key stakeholders, ranging from the NUG and PDF leaders to the more powerful EAOs, perhaps with mediation and facilitation from ASEAN, particularly Thailand. Myanmar’s future is one rare issue the United States and China can agree on – neither will want to see a disintegrated and balkanized Myanmar which becomes a cesspool of drugs and crimes.

If ASEAN, with Thailand in the lead, together with major external players from China and the U.S. to India and the broader international community, can broker a series of closed-door discussions about the country’s future political system and governance, the joint effort could lead to a new deal whereby Myanmar can still emerge as a country with greater autonomy for some of the ethnic areas.

Most likely: Myanmar becomes an uneasy confederation of autonomous statelets

The most likely scenario combines these elements. It posits that the ongoing civil war may drag on for months as the SAC uses asymmetric air power to fight rearguard actions and cling on to the seat of power in the capital of Naypyidaw. Yet eventually the SAC will succumb one way or another to the resistance.

Ultimately what can emerge is a fractured but still intact country with a reduced central government and autonomous statelets, such as Rakhine, Shan and Karen, which may agree at most to a confederation arrangement. It would form a Myanmar with mini-states within. This can still be workable for the international community if the right mix of negotiations, compromises, and agreements are found and put in place.

For industry-specific scenarios and bespoke geopolitical intelligence, contact us and we will provide you with more information about our advisory services.