The implications of Russia’s agriculture boom

Although fossil fuels will retain a key role in the foreseeable future, agriculture in Russia is booming and quickly gaining prominence. The Kremlin is touting grain exports as a path for the country to regain superpower status. A close look, however, reveals as many risks as opportunities for the country.

In a nutshell

- Russian grain production is booming

- The Kremlin is making agriculture a national priority

- The sector is vulnerable to fluctuating commodities markets

- ‘Agrobarons’ may be lining their pockets with subsidies

Since Vladimir Putin took power in 2000, Russia has earned a reputation for being a petrostate. The strong rebound of the Russian economy during 2000-2008 was driven by a spike in oil prices, combined with a 50-percent growth in oil production. Fiscal policy was stabilized, central bank reserves rebuilt, and real incomes boosted. Petroleum was the central economic focus. And while energy will surely remain a defining feature of the Russian economy for the foreseeable future, recent developments suggest that oil’s centrality may be waning.

In an otherwise sluggish economy, Russian agriculture has emerged as a success story, recording respectable growth rates and hitting new export records. Though the United States has overtaken Russia as the world’s biggest producer of oil and gas, the Kremlin can delight instead in emerging as a global leader in grain production.

‘Our second oil’

In 2016, for the first time since the end of the Russian Empire, Russia reemerged as the world’s largest exporter of wheat. Inspired by the moment, then-Minister of Agriculture Alexander Tkachev proclaimed that “grain is our second oil,” and went on to predict that agricultural export revenues might one day exceed those from energy.

That is unlikely and may not even be desirable. Although a solid case can be made that breaking Russia’s heavy dependence on hydrocarbons exports would benefit its economy, exchanging that for a dependence on grain exports could make things worse. Both are commodities and thus hostage to developments in international markets that are beyond the exporting nation’s control. In contrast to hydrocarbons, grain is also hostage to the vagaries of weather, so export revenues will be contingent on two sources of (at times extreme) volatility. An even more important difference is that while hydrocarbons provide the government with healthy rents, agriculture requires substantial subsidies.

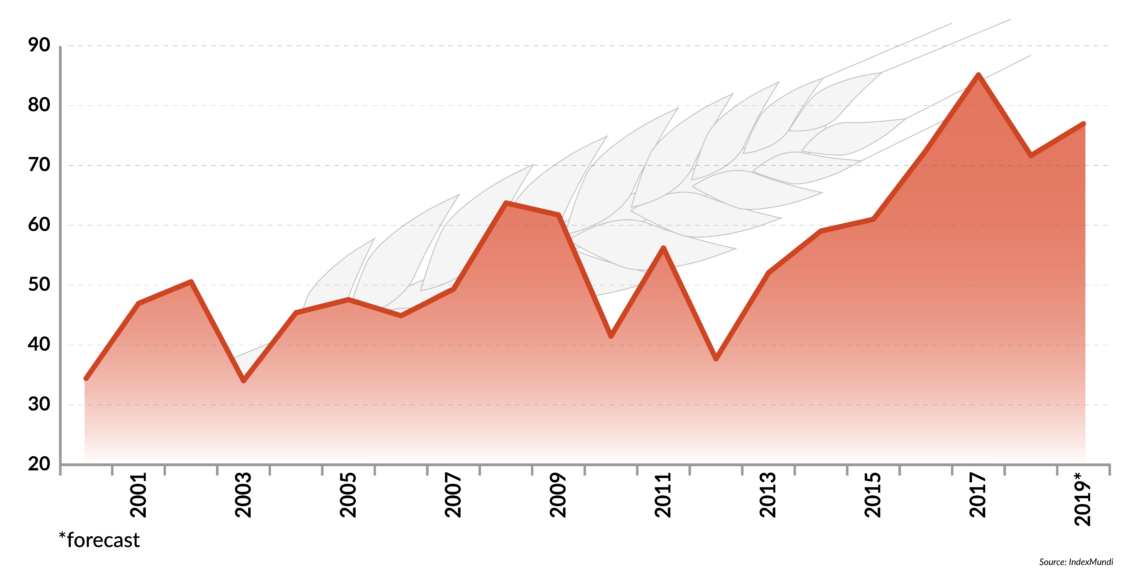

That said, it remains understandable that Russian officials are upbeat about the country’s recent agricultural performance. Optimism was boosted by the bumper year 2017, which saw a record grain harvest of 135.4 million tons (mt), and record grain exports of 52.4 mt. Compare that to 2010, which saw a grain harvest of 61.0 mt and exports of just 4.1 mt. The impact on export revenues has been substantial. In 2018, total agricultural goods exports grew by 20 percent, to reach $25.9 billion.

Agriculture is now Russia’s fourth-largest export earner, after oil, gas and minerals.

Agriculture is now Russia’s fourth-largest export earner, after oil, gas and minerals. Even President Putin has highlighted that agricultural exports bring in almost twice the revenue earned from arms exports. Commenting on the 2019 grain harvest, Agriculture Minister Dmitry Patrushev claimed that Russia is now winning back its status as an “agricultural superpower,” and suggested that the future is bright: “We have an ambitious goal of raising exports of our agricultural industry to $45 billion by 2024,” he said.

Sustained increase

Natural fluctuations play a role here. The total grain harvest for 2018 was down to 112.9 mt and the forecast for 2019 is 118 mt. As the forecast for grain exports is also being scaled back, to 46-48 mt, it is possible that a buoyant Ukraine, on track to export 49 mt of grain, will overtake Russia as a leading grain exporter. But this will be a temporary blip.

Most experts agree that Russia is well on track to a sustained increase in grain production, with output levels of around 140-150 mt becoming the new norm. Global demand forecasts also suggest that there will be markets for increased output. As prior claims of Russia emerging as an “energy superpower” have faded, it is understandable that agriculture is being hyped as a new basis for Russian greatness. But much as the vision of energy power turned out rather hollow, the current vision of agricultural power needs to be qualified in several important respects.

The path leading to today’s situation is marked by three milestones, each with different implications for future developments.

National priority

The first came in 2005, when the Kremlin declared the development of agriculture a national priority. During the 1990s, the transition from state and collectivized to private farming brought severe disruptions. The Kremlin’s ambitious new plan was to provide economic support for investment, along with technological and structural change. In line with President Putin’s overarching belief in consolidation and “national champions,” this would entail a movement toward a small set of very large-scale agroholdings.

Facts & figures

Going with the grain

Russian wheat production, 2000-2019* (million metric tons)

Of course, there is nothing peculiar about states providing subsidies for farming. American agriculture is rife with accounts of farmers being paid not to grow anything, and one might be forgiven for believing that the massive subsidies entailed in the Common Agricultural Policy constitute the very raison d’etre for the European Union. Yet, there are peculiarities in the Russian case that raise serious questions about value-added versus rent-seeking. Is the economic support designed to mesh with the national interest, or is it just another way to line the pockets of well-connected oligarchs?

Food security

The second milestone came in 2010, with the introduction of a Food Security Doctrine. The Russian word used was bezopasnost, which suggests considerations of national security. By moving toward self-sufficiency in food production, the authorities hoped there would also be gains in food safety, ensuring that Russian consumers had access to healthy foods.

On the former count, domestic production targets were set ranging from 95 percent in grain and potatoes, to 90 percent in milk and dairy products, 85 percent in meat and meat products and edible salt, and 80 percent in sugar, vegetable oil, and fish products. Except for dairy products and edible salt, these targets have been reached and exceeded. In addition to the boom in grain production, Russia is now a net exporter of poultry, self-sufficient in pork and making strong headway in beef. There is a boom in greenhouse construction for vegetable production.

In the realm of food safety, President Putin has claimed that “Russia can become the largest world supplier of healthy, ecologically clean and high-quality food that the Western producers have long lost.” The upside of this emphasis on quality has been a growing focus on locally grown ecological foods, with specialized outlets in the larger cities. While this is well in line with international trends, there are also downsides.

Russian ban on GMOs has elements of making a virtue out of necessity.

The focus on “ecologically clean” food is partly aimed at the use of genetically modified organisms (GMOs), which were banned in Russia in 2016. Given the crucial dependence of U.S. agriculture on GMOs, one is led to suspect that the Russian ban has elements of making a virtue out of necessity – being unable to match U.S. advances in the agrosciences, the Kremlin has opted out and switched to moral grandstanding.

More sinister is the increasing official focus on quality of food imports. The Federal Service for Veterinary and Phytosanitary Surveillance (Rosselkhoznadzor) has shown an uncanny ability to detect problems in imports from countries that are at odds with the Kremlin. Russia can therefore use food safety concerns both to evade World Trade Organization rules when protecting its domestic industry and as a foreign policy tool.

Banning imports

The third milestone in the emergence of Russian agriculture as a strategic sector came with the 2014 introduction of Russian countersanctions, banning imports of agricultural goods from countries that participate in sanctions against Russia over its actions against Ukraine. Russia closed its markets to countries that in 2013 had accounted for more than half of its imports of pork, poultry, fish and seafood, vegetables and dairy products.

The impact on Russian consumers has been unequivocal – increased prices and reductions in both quality and variety. An immediate consequence has been smuggling and relabeling, likely putting considerable sums into the pockets of well-connected operators. Salmon and parmesan cheese imported from Belarus may, for example, not be credibly assumed to have originated in that country. Rosselkhoznadzor has also documented serious cases of adulteration of processed foods, such as palm oil being substituted for butter.

A less obvious consequence has been the impact on domestic food production. Part of the response to the collapse in imports has been (more expensive) imports from faraway countries. But much of the slack has been picked up by domestic producers. The structure of Russian agriculture has transformed in favor of the large agroholdings.

The main question here concerns sustainability. If the Russian embargo were to be lifted – something that is unlikely to happen any time soon – could domestic producers stay competitive with the foreign food producers that had such a grip on the Russian market before 2014?

Grain boom

The centerpiece of the story is grain, which essentially means wheat. More than half of the agricultural sector remains focused on farming. Of the crops grown on Russian farmland, 80 percent is grain, of which 60 percent is wheat.

The recent boom has been driven by several factors, including a few years of favorable weather. Climate change has also played a role, making larger areas to the north accessible to farming. But a closer look at maps showing new lands taken into cultivation offers a rather scattered picture: much of the expansion has taken place inside traditional farming areas. Also, a big share of future output growth is expected to come from intensification, rather than expansion into marginal areas.

The real driver is the agroholdings: large, vertically integrated businesses that have adopted Western technologies like fertilizers, smart irrigation and hi-tech drones to increase yields and allow unused lands to be cultivated. Their impact on output is undeniable. Yet, there are serious questions about added value.

Fertilizer use will reach a point of saturation, where ecological damage becomes a problem. Deployment of advanced technologies is a question of marginal cost and benefit. Since the agroholding owners are close to the Kremlin, they may be subsidized to push operations beyond what economic prudence would dictate.

Political considerations may cause the agrobarons to go along with policies that are economically unsustainable.

The fact that expansion of the cultivated area has become a high policy priority constitutes a particular problem, risking the emergence of Soviet-era type political campaigns where local officials apply undue pressure. For example, taxes are being introduced on unused farmland. Political considerations may again cause the agrobarons to go along with policies that are economically unsustainable. The opacity of the subsidy system makes it very hard to tell exactly who gets what and why.

There is also the question of implied needs to expand infrastructure, ranging from grain elevators to railways and ports. Taxpayers will likely bear much of the cost for these investments, while the agroholdings cash in on the export boom. Scholarly studies have shown that the smaller private farms would be better suited to lead development of the sector, but the system is clearly structured in favor of large scales and political connections.

Moving up the value chain

Returning to the parallel between energy and agricultural commodities, the big question looking forward concerns the potential for successful processing. It is true that a large part of the potato harvest goes into making vodka, and that an increasing share of the barley harvest goes into an expanding breweries industry. Roughly 70 percent of the wheat also goes into domestic consumption, mainly making flour.

But exports remain commodity-based, and like the price of oil, the price of Russian wheat has dropped considerably. In 2012, Black Sea wheat sold at more than $350 per ton. Prices for the new 2019 crop are just above $180. Russia does have the advantage that wheat is mainly grown in the southern regions, close to Black Sea ports for export to the Middle East and North Africa. Yet, the wheat is mostly of low quality, giving it a limited range of uses – suitable for baked flatbread but not for high-quality noodles.

That last point highlights the need to move away from commodity exports, which essentially means developing the lagging meat and dairy industries and adjusting the output of feed grains accordingly. Can the agroholdings lead the way up this quality ladder? Early indications suggest they can. As in the oil industry, Western partners have made a big difference, supporting imports of breeding cattle and the application of discoveries from the agrosciences.

But this may be a case of picking the low-hanging fruit. Russia’s dismal track record of animal husbandry explains why animal products (excluding fish and seafood) account for just over 10 percent of exports. In France, the corresponding figure is higher than 40 percent. The jury is still out on whether protection and import substitution will be conducive to learning and enhanced competitiveness.

The main takeaway is that the future for expanded production, and thus grain exports, looks good. Russian grain exports are projected to increase by 60 percent between 2015 and 2030, boosting export revenues. Even the lagging meat and dairy industries may be picking up speed, realizing the goal of food security. But the question of added value will remain. Wariness about foreign competition will likely keep Russia’s food sanctions in place, at great cost to its consumers.