Russia’s ‘food superpower’ vision: opportunities and pitfalls

Russia wants agriculture to fuel its rise. In recent years, its production of grains, especially wheat, has rocketed. But absorbing the increase, whether through domestic consumption or exports, poses some big challenges. And even if it overcomes those, Russia’s agriculture sector is likely to remain dependent on unprocessed products.

In a nutshell

- Russia’s agriculture sector is enjoying a boom

- Counter-sanctions and climate conditions are fueling an increase in grain production

- The domestic population and export infrastructure may not absorb the increase

- Russia will likely only continue to export unprocessed grain

Russia’s quest for restored greatness is about to take a new and perhaps unexpected turn. After Moscow first nurtured a belief that Russia could become an “economic superpower” and then switched to visions of an “energy superpower,” the latest twist is to make it a “food superpower.”

In his December 2015 address to the Federal Assembly, President Vladimir Putin claimed that Russia could become “the largest world supplier of healthy, ecologically clean and high-quality food which the Western producers have long lost, especially given the fact that demand for such products in the world market is steadily growing.” Pundits latched on, and the idea of Russia as a superpower in food began to proliferate.

Considering the Soviet/Russian heritage of environmental degradation and prolific use of agrochemicals, notably highly toxic pesticides, the focus on “ecologically clean” food is especially striking. The use of genetically modified organisms (GMOs), which is now a mainstay of agriculture in the United States, has been banned in Russia since 2016, offering the Kremlin room for moral grandstanding.

New frontier

Recent developments give reason for enthusiasm about food as a driver for Russia’s rise. The last four years have seen agriculture emerge as a real success story of the Russian economy. The main achievement has been tremendous growth in the production of grains, especially wheat.

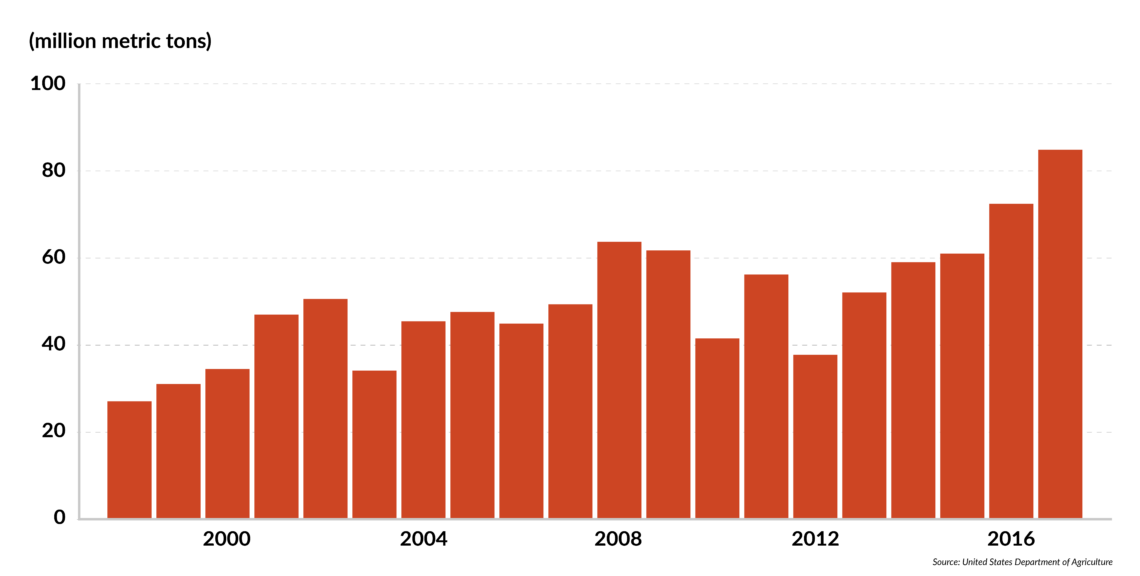

In 2000-2005, the total grain harvest was less than 79 million tons (mt) on average. In 2009, it broke 100 mt, and in 2017 it reached a record high of 135.4 mt. Wheat production increased from 56.2 mt in 2011 to 85 mt in 2017. This development has also fueled a boom in agricultural exports, which have grown 16-fold since 2000.

Facts & figures

Bumper harvest

Russia's wheat production, 1998-2017

Russian wheat exports exceeded U.S. wheat exports in 2016, and in 2017 it topped those of the European Union. It currently holds 22 percent of the global wheat market, with the EU and the U.S. trailing at, respectively, 14 and 13 percent. Russian wheat exports have pushed out those of the U.S. in Egypt and made inroads into key French markets like Senegal and Morocco. Russia even landed a big wheat-export contract with Mexico, traditionally a “home market” for U.S. producers.

Russia’s revenues from food exports have outstripped those from weapons exports.

One important consequence of the boom in agricultural production is that, beginning in 2015, Russia’s revenues from food exports have outstripped those from weapons exports. In March 2018, President Putin noted that “agriculture exports exceed arms sales by more than a third.” He put the former at $28.8 billion and the latter at $15.6 billion.

The two main factors behind the surge in production have been favorable weather and the Russian counter-sanctions that were introduced in retaliation for Western sanctions over Russia’s aggression against Ukraine. While the embargo on food imports has allowed for the expansion in domestic output, the weather has improved supply.

The last time Russia suffered a drought was in 2012. Most regions have since enjoyed favorable weather. While this may be dismissed as a temporary change causing a short-term hike in grain production, global warming offers a more reliable basis for a positive longer-term trend. Climate studies predict that compared to the late 1980s, Russia’s grain-producing regions will see temperature increases of 1.8 degrees by 2020 and of 3.9 degrees by 2050.

This implies that the agricultural “frontier” has been moved further to the north and that the prospects for successful land reclamation have improved. Visions for the latter are bold, as is the level of Russian state support.

Production growth

In October 2015, the Ministry of Agriculture called for a stunning 10 million hectares of unused land to be brought into production and cultivated with 5,000 tractors and combines. This fed into an already developing trend whereby cultivated land increased from 43.3 million hectares in 2006 to 47.1 million hectares in 2016. A further 620,000 hectares were added in 2017, and the growth has continued this year.

Facts & figures

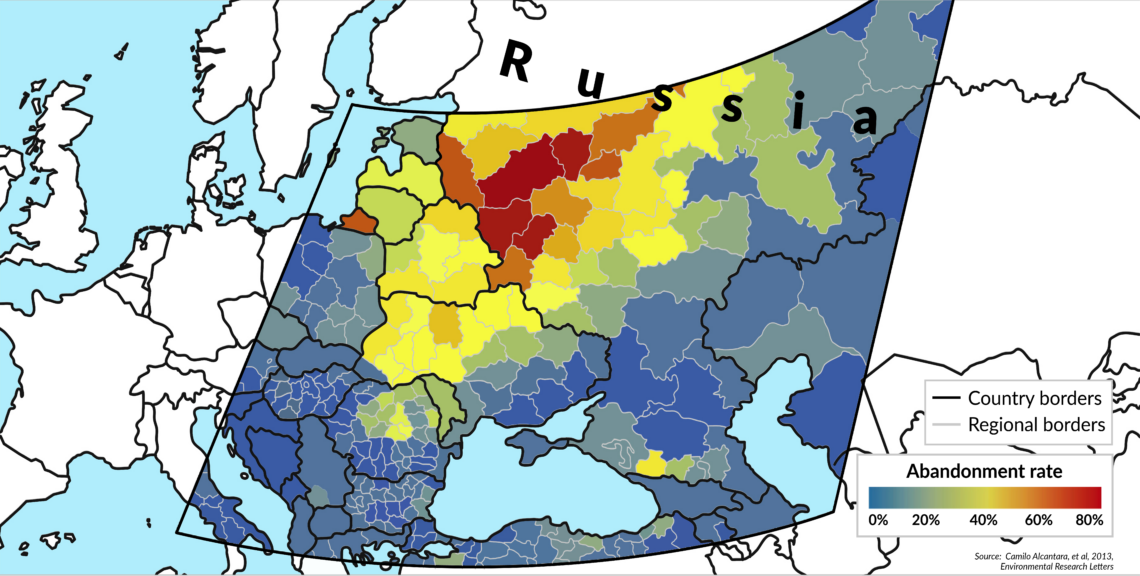

Ready for a farming comeback

Abandonment rate of farmlands in Russia and other European countries

The plan is plausible. It has been estimated that 56.6 million hectares of cropland were abandoned from 1991-2000, mainly because investing in these areas was no longer profitable once Russia turned to a market economy. This is now changing. A wager on state support for consolidated “superfarms” will bring improved technology, such as increased use of drones, robots and driverless equipment. It will also lead to a rise in fertilizer use. Around 40 percent of farms still use no fertilizer.

Based on these trends, the outlook for continued production growth is good. An output of 140-150 million tons of grain could soon become a reality. However, such huge production brings its own set of problems. The capacity to absorb the growth is limited both by domestic consumption patterns and by a shortage of the infrastructure needed to store and transport the grain.

Demographic changes would seem to support predictions that demand will grow. Russians have begun having more babies, so there will be more mouths to feed. However, this is offset by changing household consumption patterns. As Russians buy less meat due to increasing economic hardship, livestock numbers will shrink and the demand for feed grains will fall. The number of beef cattle and dairy cows dropped from 19.9 million in 2010 to 18.6 million in 2017. This change will further boost the supply of available grain.

Bottlenecks emerging

The rise in grain production will put a lot more pressure on the infrastructure needed to support exports. Bottlenecks are rapidly emerging. Having Egypt as a key export market indicates that capacity in Black Sea harbors should increase. And the rising role of China adds pressure on the rail transport system, which is not in good shape. Rail cars used for grain transport are increasingly being retired due to old age. The production of new rail cars cannot make up the gap, and special permissions are being issued to use old rolling stock.

The Kremlin’s wager on wheat will depend on the vagaries of international commodities markets.

The Kremlin’s wager on wheat will also depend on the vagaries of international commodities markets. Although a growing global population should generate increasing demand, the consequences of the collapse in energy prices that began in 2009 should raise warning flags. Experience from the Russian arms sector may do the same.

Much as Russian weapons are mainly sold to countries that cannot get them from NATO sources, Russian food exports are often of low quality and are sold mainly in peripheral markets like Egypt, Turkey, Iran and Indonesia. Russia’s poor track record in animal husbandry makes grains the only real candidate for increasing agricultural exports. Even here quality is an issue, due partly to the climate and partly to the insufficient use of fertilizers.

The key question is whether Russian agriculture will, in economic jargon, be able to “climb the quality ladder.” The likely outcome is that it will not, and that its mainstay will remain unprocessed commodities. Again, this parallels Russia’s experience in energy exports.

An important reason for pessimism is the emerging pattern of resource nationalism. Memories of the Cold War loom large in the Kremlin. During the tense years 1980-1985, the Soviet Union was forced to import 30 million tons of U.S. wheat annually, draining its hard currency reserves. The Kremlin wants to ensure that situation never repeats: food self-sufficiency is to be achieved by 2022. As in the days of the Russian Empire, Russia is again to become a net exporter of food, even if comparative advantage would dictate otherwise.

Mixed results

The counter-sanctions against food imports provide a good illustration of the consequences that may follow from this ambition. The immediate impact of the embargo was a decrease in imports for domestic food consumption, from 35 percent in 2013 to 20 percent today. By 2016, food imports from the EU had fallen by 40 percent compared to 2013, and the trend continues.

This has boosted domestic agribusiness. Shares in companies like Rusagro, PhosAgro and meat producer Cherkizovo spiked after 2014. While this supports innovation and productivity, it also feeds into growing concentration in the Russian economy. The top 20 companies currently produce 60 percent of all pork and 49 percent of all animal feed. The top 25 produce 43 percent of all meat and the top 10 produce 60 percent of all broilers.

This development aligns with the general pattern of ever tighter links between business and the state. Friends of President Putin have been especially fortunate. One example is the Renova Group, owned by Viktor Vekselberg, which leads a countrywide charge in building greenhouses.

Foreign investment in Russian agriculture has dropped by a third, from a peak of $900 million in 2013.

The success of Russian agribusiness has been driven by a steep decline in imports of beef, pork, poultry, vegetables and dairy. Foreign investment in Russian agriculture has dropped by a third, from a peak of $900 million in 2013.

Although the policy of import substitution has been hailed by the Kremlin as a boon to the country, it has not helped consumers. One consequence has been the emergence of a lucrative market for contraband, such as salmon and Parmesan cheese allegedly originating in Belarus. Well-connected middlemen are raking in substantial margins, and consumers face rising prices.

Long-term costs

Another consequence has been the increased use of low-quality substitutes. For example, Russian imports of cheap palm oil more than doubled between 2012 and 2016, making the country the largest importer of such oil. This suggests that palm oil is being used in domestic cheese production. In 2015, food quality watchdog Rosselkhoznadzor found that in some regions, 78.3 percent of cheese and 25 percent of other dairy products had been adulterated.

So while Russia may continue expanding its grain production, and may even overcome infrastructural bottlenecks to facilitate export expansion, there may still be substantial longer-term costs, ranging from eroded consumer welfare to damage to vital economic institutions.

More than half of the agricultural sector is still devoted to farming. Of the crops grown on Russian farmland, 80 percent is grain and 60 percent of that is wheat. The above-mentioned poor track record in breeding has left animal products (excluding fish and seafood) accounting for just over 10 percent of exports. For comparison, in France, that number is above 40 percent.

Here, the parallel to the old vision of Russia as an energy superpower is again relevant. Much as the boom in energy exports rested on gas and crude oil, the surge in agricultural production is driven by commodities with a low degree of processing. This is in line with a long-term Russian model of economic growth that rests on the extraction and export of commodities. Placing even greater emphasis on a boom in wheat exports will cement this pattern.