Nordic media take aim at Russian threats

Investigative journalists have exposed Russian spy operations and highlighted the vulnerability of critical undersea infrastructure to sabotage.

In a nutshell

- Russia uses spies under diplomatic cover and civilians to gather intelligence

- The Kremlin’s naval operations around Nordic nations are more aggressive

- Western governments are showing restraint and limiting public disclosures

Beginning in mid-April, public television broadcasters in the Nordic countries aired a series of three jointly-produced documentary programs with revelations about clandestine Russian intelligence operations. The programs made quite a splash, mainly because they shined a light on how vulnerable Europe is to covert Russian attacks against critical infrastructure.

The investigation was wide-ranging, depicting Russian trawlers loitering around ports and bridges along the Norwegian coastline, Russian underwater research vessels cruising around wind farms in the North Sea and Russian intelligence officers working under diplomatic cover in embassies in the Nordic countries. The message was driven home with suggestive photography.

One segment shows the Russian trawler Taurus gliding slowly past an American fast-attack submarine, the USS South Dakota, moored at a naval base in the Norwegian Arctic port city of Tromso. Records of prior movements show Taurus frequently on location to monitor NATO drills. Its arrival at Tromso was timed to coincide with the scheduled visit by the American submarine. On the way out from the commercial port, the Russian vessel passed so close to the U.S. submarine that there was ample time for photography and perhaps more.

In another segment, a Danish journalist in a small rubber boat is shown approaching the Russian underwater research ship Admiral Vladimirsky, at anchor just off the Danish coast at Sjallands Odde. When the reporter gets close enough to start taking pictures, he is confronted by a sinister-looking man who appears on the deck of the Russian vessel, face covered and carrying a military assault rifle.

Reporters are shown photographing Russian diplomats and conducting ambush interviews. By comparing the footage against databases of known Russian intelligence officers, they compile lists of agents they claim are working under diplomatic cover. Those lists were handed over to the respective Nordic governments.

Same old Russian behavior

To people with knowledge of Russia, none of this is new. The Russian Federation has continued the Soviet practice of using civilian shipping to gather intelligence as well as deploying intelligence officers who work under diplomatic cover. The reason is that such ships can move inside territorial waters, while naval vessels need permission to enter. Local mariners are used to seeing Russian trawlers with odd-looking antennas as well as Russian ships pretending to be involved in underwater research.

What is new is that the public is now more aware of the extent of harm that Russia is capable of inflicting. Those involved deserve much credit for well-researched investigative journalism. Added spice is provided by the fact that the sabotage against the Nord Stream pipelines occurred during the ongoing investigation.

Read more by Stefan Hedlund

Russia’s emerging war economy

The Arctic in Russia’s crosshairs

The nuclear threat from the Kola Peninsula

One problem is that these accounts tend to downplay the increasingly defensive nature of Russian operations. Following the setbacks of its conventional forces in Ukraine, the Russian military leadership must be truly fearful of a shooting war with NATO. This implies that the importance of its nuclear arsenal has increased, and nuclear ballistic submarines based on the Kola Peninsula are key in that arsenal.

The potential threat to those bases has been underscored by the recent reactivation of the U.S. Second Fleet, enhancing the U.S. presence in the North Atlantic and the Arctic, and by the accession of Finland to NATO. The main mission of Russia’s Northern Fleet is no longer to engage U.S. carrier groups offensively, but rather to protect the fleet from being detected by American fast-attack submarines. This explains why Russian intelligence is tracking and intimidating both American submarines and vessels of the Norwegian coast guard that might engage in forms of antisubmarine warfare.

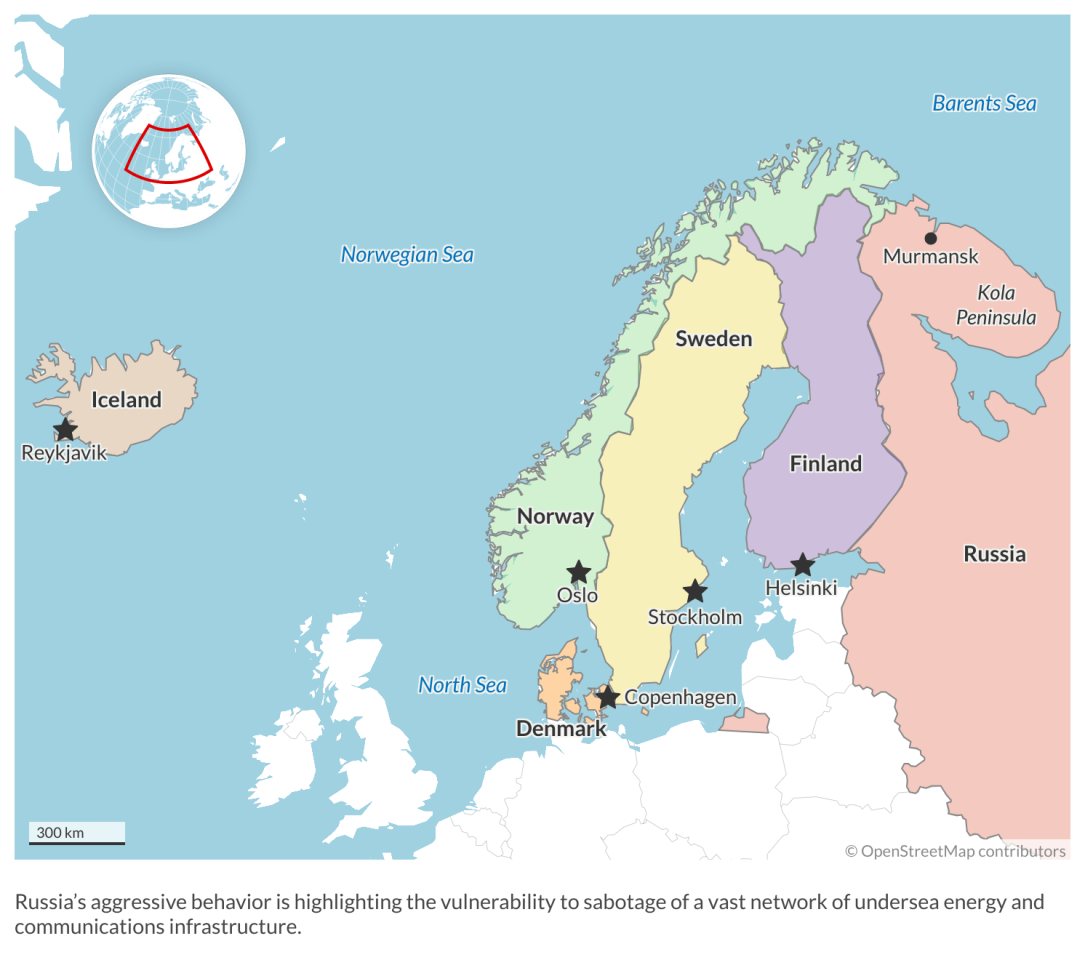

Targeting energy and communications infrastructure

While the risk of open Russian military aggression against NATO may be discounted, one danger is that Russia will balance defeat in Ukraine with increasingly aggressive behavior in other theaters. An important target is the vast complex of underwater energy and communications infrastructure that rests on the bottom of the Arctic and the North Sea. This complex includes thousands of kilometers of gas pipelines and even more fiber-optic and power transmission cables. Spooked by the sabotage of Nord Stream, and by incidents of drones and individuals loitering on sensitive locations, the Norwegian government has expressed great concern.

Although Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg has vowed that NATO will do all it can to ensure the safety of this infrastructure, in practice it is impossible to offer adequate protection. Given that natural gas from Norway has become critical in replacing the Russian supply for the European Union, Brussels also has ample reason to be concerned.

Facts & figures

Fleets of Russian civilian spies

Russia is gearing up to escalate the threat. According to a revised Russian naval doctrine released last summer, all civilian shipping is required to assist in gathering intelligence. This means that several hundred ships will be taking pictures and reporting the movements of NATO vessels. The most suspicious are known as “ghost ships,” sailing with their automatic identification system (AIS) transmitters switched off. The AIS shows the identity, current speed and origin of a vessel.

In a possible warning shot, in January 2022 two fiber-optic cables that link the Norwegian Svalbard archipelago with the mainland were cut. Located halfway between the North Pole and the Norwegian mainland, Svalbard is home to one of the world’s largest ground stations for commercial satellite communication. It is a high-value target, and there was a smoking gun: the Nordic countries’ television investigation showed that the Russian trawler Melkart 5 had passed over the cables 130 times before the breaks occurred.

Norwegian police claim that dragnets were used to cut the cables. Pictures of drag marks on the seabed fit pictures of the trawl hanging from the trawler’s aft door. At the time of the incident, there were three Russian vessels present. Due to antiquated legislation, it has not been possible to prosecute.

An even greater threat may be seen against the emerging forests of offshore wind farms that are intended to serve as the mainstay for European electricity generation. The Admiral Vladimirsky is shown to have been loitering in and around seven different wind farms, off Scotland, the Netherlands and Denmark. It may be assumed that she and other Russian “ghost ships” have been engaged in finding suitable points to attack – such as the transformer stations that serve as exit points for power cables.

Operations of this kind are coordinated by a special-purpose department within the Russian Defense Ministry, the Main Directorate of Deep-Sea Research (known as GUGI). Tasked with mapping and preparing to attack underwater infrastructure, it has a fleet of surface vessels, submarines and special-purpose submersibles at its disposal. If push comes to shove, it will be up to these forces to cripple European underwater energy and communications infrastructure.

Russia is losing the war of secrets

Given that the counterintelligence services of the Nordic countries are likely familiar with these operations, and have plenty of additional information of their own, the question is what impact the media revelations will have. This is where the threat that emanates from Russian intelligence officers working undercover as diplomats comes into focus.

From a perspective of information gathering, it is probably not that much of a concern. The main takeaway from the recent Pentagon leaks was not the exposure of specific American secrets, but that U.S. sources consider Russia to be “an open book.” And Ukrainian intelligence obviously has its own access to the most intimate of Russian secrets.

The real danger emanates from Russian agents seeking to weaken the Western resolve to support Ukraine. They may do so by mobilizing the substantial fifth column of Russian sympathizers that have infiltrated both media and government in other countries, more so in some than others.

Scenarios

The outing of Russian diplomats as intelligence officers suggests two possible scenarios.

The first is a clean sweep. Since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, around 500 Russian diplomats have been expelled from different European countries. They will be difficult to move to other embassies and difficult to replace. As diplomatic cover for illegal agents is exposed, they will have to take greater risks, leading to more arrests and further damage.

If other public broadcasters were to follow the Nordic example of investigating and making public as much as possible about Russian clandestine operations, it could result in a groundswell of public anger that would cripple Russian influence operations.

The airing of the Nordic documentaries caused prompt reactions from two of the concerned governments. On April 13, Norway expelled 15 Russian diplomats, and on April 25, the Swedish government expelled five. Denmark had already cleaned house by expelling 15 Russian diplomats in April 2022. There are two possible interpretations for why Sweden and Norway are holding back from expelling all known intelligence agents and avoiding all-out confrontation in the information war.

One explanation is that the expulsion of Russian diplomats tends to be a game of tit-for-tat. Russian retaliatory expulsions reduce embassy staff, ending channels of communication and access to information. Canada makes this case, abstaining from expelling even a single Russian diplomat.

A weightier argument is that countering Russian moves is easier if both the agents and members of their networks are known. In some cases, some may even be recruited by the West as double agents. While mass expulsions harm Russian intelligence, they could also be problematic for Western counterintelligence.

As the third Nordic documentary program was set to be aired, with promised revelations about Nord Stream, the Danish government revealed it had tracked and photographed a Russian vessel loitering near the pipelines just four days before their sabotage. Named SS-750, it was a specialized vessel with a submarine on board. In the search for a culprit, this is a more likely candidate than the prior “revelation” that a group of suspicious Ukrainians had rented a small sailing boat in a Polish harbor. The program then went on to show that two additional Russian “ghost ships” had been active in the area. Although it fell short of proof of Russian culpability, it provided an effective counterpoint to claims by assorted Western intellectuals that America is guilty.

If these revelations succeed in prompting Western governments and intelligence services into coming clean about what they know, investigative journalism will have served an important purpose. The problem is that such official disclosures would mean moving into uncharted waters, with unknown dangers.

Western governments are likely to exercise restraint. In so doing, they will play into the hands of the Russian fifth column inside Western democracies. The counterargument is that continuing to play the current game, limiting both expulsions and public revelations, will keep the Russian side in the dark about the next move. It may or may not be the wisest course, but it is the likeliest scenario.