The Arctic in Russia’s crosshairs

Intense military buildups and drills have replaced international cooperation in the Arctic. War is unlikely but expect growing East-West tensions.

In a nutshell

- Russia holds the Arctic Council’s rotating presidency for 2021-2023

- Its seven non-Russian members halted participation in all meetings

- Russia’s and NATO’s military presence in the Arctic is increasing

Global warming and the melting Arctic ice cap were once associated with visions of a new era of international cooperation on initiatives like hydrocarbon exploitation and speeding up east-west transport via the Northern Sea Route. Now, those phenomena have triggered another type of heating – in the militarization race between Russia and the NATO alliance.

As Western governments resolved to stand by Ukraine after Russia’s full-scale invasion, cooperation was replaced by open conflict, and there likely can be no going back any time soon. The danger of a military confrontation in the Arctic is the highest since the peak of the Cold War.

A harbinger of coming trouble was the 2014 launch of the first stage of the Russian invasion, the Crimea takeover.

In 2010, Norway and Russia decided to resolve a long-standing dispute over the common border in the Arctic. That was seen to pave the way for joint exploitation of the massive offshore deposits of oil and gas. Norway was not alone in getting ready. Global energy giant Exxon struck a multibillion-dollar deal with its Russian counterpart Rosneft.

Despite this Russian activity, the Western powers remained hopeful that mutually profitable energy cooperation would prevail.

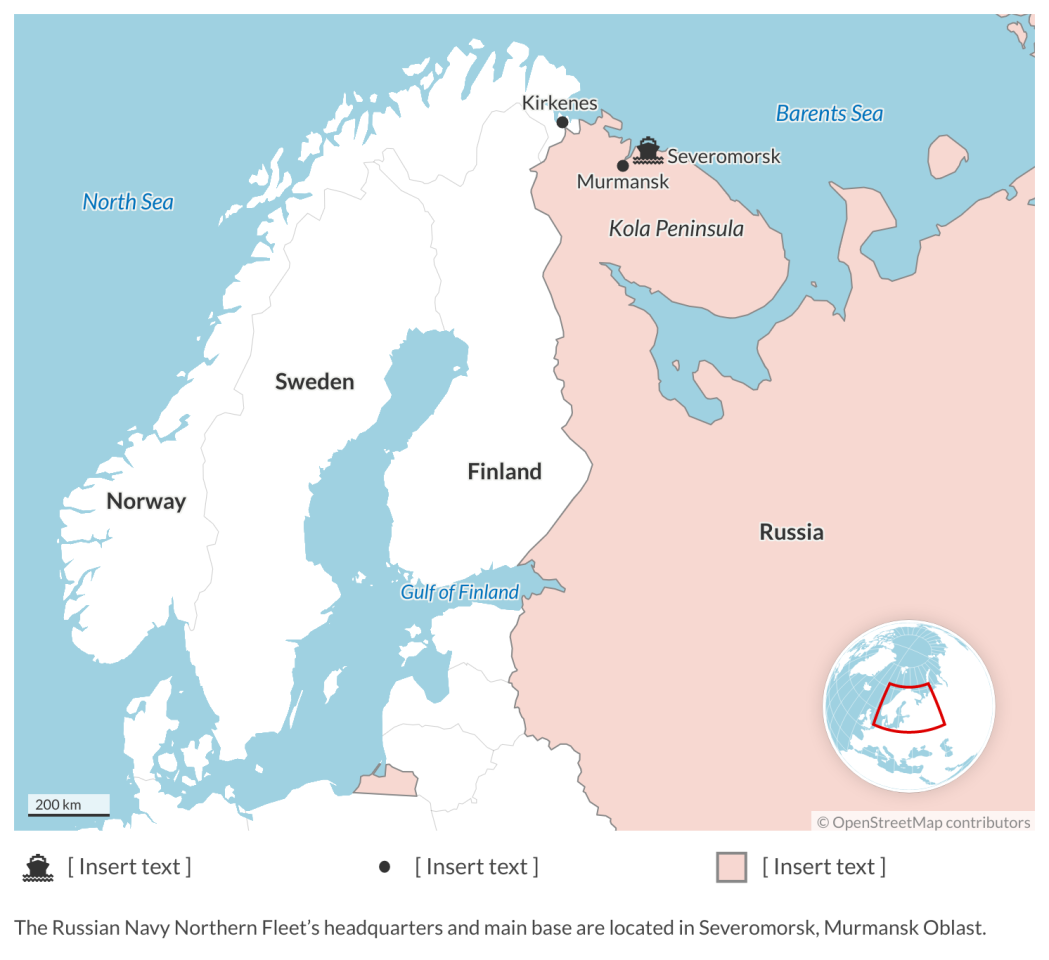

Following the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014, all of this had to be put on hold. While Exxon and others began pulling back from all Russian ventures, the Russian military embarked on a program for Arctic militarization. Aimed at projecting power into the north and at protecting the basing areas for the Northern Fleet at the Kola Peninsula, the program was comprehensive.

Russia’s ambitious militarization program

The land component entailed upgrading long-neglected military bases and forming special-purpose arctic brigades. The maritime counterpart saw the addition of modern ballistic submarines, testing highly capable naval weapon systems, and an expansion of the nuclear-powered icebreaker fleet.

Despite this Russian activity, the Western powers remained hopeful that mutually profitable energy cooperation would prevail and that the Arctic would not be transformed into another arena for military confrontation. The full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 caused all such hopes to collapse.

Hardening attitudes

Ironically, Russia holds the rotating presidency of the Arctic Council for 2021-2023. Moscow was still looking at cooperative relations when it took over the helm. A policy document published in March 2020 called for the “strengthening of good neighborly relations with the Arctic states” in economic, scientific, cultural and cross-border cooperation. The other members voiced no open objections to the Russian leadership.

Facts & figures

The Arctic Council

The Arctic Council was created in Ottawa in 1996. Member states of the council include Denmark, Canada, Norway, the U.S., Russia, Sweden, Finland and Iceland. The council also has permanent participants drawn from groups that represent communities and peoples indigenous to the Arctic. The body’s secretariat is located in Tromso, Norway.

Norway was a case in point. It continued meeting Russian representatives at the border town of Kirkenes, where good personal relations had long allowed practical issues to be resolved locally. Together with neutral Finland and Sweden, it also maintained cooperation within the intergovernmental Barents Euro-Arctic Council and the Barents Regional Council. The latter body has 13 member counties and a representative of the indigenous peoples in the northernmost parts of Finland, Norway and Sweden and North-West Russia. Both councils had served to facilitate cooperation in the Barents Region in areas ranging from health and environment to maritime search and rescue.

Read more on Russia’s Arctic

Russia’s Arctic economy is heading for decline

The initial reaction to the full-scale attack on Ukraine was soft. On March 3, 2022, the seven non-Russian members of the Arctic Council announced a temporary halt to participation in all meetings of the Council. A year later, a senior United States official could note that “Moscow’s decision to invade its neighbor, an independent and sovereign state, makes cooperation virtually impossible for [the] foreseeable future.” The conclusion was that work within the Arctic Council must proceed without Russia.

Russia, in return, presented a new version of its Arctic strategy that deleted all prior references to multilateral regional cooperation formats like the Arctic Council and the Barents Council. Reflecting concern about the viability of the Northern Sea Route, it also emphasized Russian self-reliance, calling for “import independence of the shipbuilding complex.” Sanctions have constrained Russia’s ability to build icebreakers and to purchase ice-capable tankers from Western shipbuilders.

Norway at the center of the rivalry

Norway, an Arctic frontline state with a long coastline that reaches the Russian border, is at the epicenter of the mounting tensions. Oslo is seriously concerned about increased activity by Russian submarines and aviation. Norwegian intelligence claims that the Russian Northern Fleet vessels are being deployed with tactical nuclear weapons on board for the first time since the end of the Cold War.

Facts & figures

The U.S. has responded by increasing its involvement. Since the height of the Cold War, the U.S. Marine Corps has operated a prepositioning program in Norway. It uses cave complexes to store equipment and supplies sufficient to sustain a Marine Expeditionary Brigade in combat for 30 days. In recent years, U.S. Marines have deployed to Norway and Finland to enhance their skills in winter warfare.

During 10 days in March this year, 12,000 Norwegian and allied troops took part in the biannual Joint Viking ground forces exercise, while 8,000 participated in the parallel British marine exercise Joint Warrior, conducted off the coast of Norway. In tandem with these drills, the Norwegian Home Guard mobilized 4,200 troops for a three-week training exercise.

The strategic importance of the Arctic revolves around the Russian Kola Peninsula, which is home to the Northern Fleet and its ballistic missile submarines. In 2018, in response to mounting Russian assertiveness in the North Atlantic and the Arctic, the U.S. reestablished its Second Fleet, which had been deactivated in 2011. Its importance is now on the rise.

NATO countermeasures

In late February 2023, the U.S. Strategic Command sent one of its E-6B Mercury planes to Iceland. Colloquially known as a “doomsday plane,” it is designed to serve as a command-and-control center for the U.S. Navy, enabling secure communications with its strategic nuclear submarines. In an emergency, the plane can be used as a command post for the president, who may authorize the launch of nuclear weapons. Given that the plane is hard to detect on radar and has considerable endurance, its forward posting was a clear signal to the Kremlin.

A similar signal was sent in early March when the U.S. Air Force sent a B-52H Stratofortress strategic bomber to patrol the Gulf of Finland. Being capable of carrying nuclear weapons, it approached within 200 kilometers of St. Petersburg, where it turned south across the three Baltic republics. Just shy of the border between Lithuania and the Russian Kaliningrad exclave, it turned west, hugging the Russian border until it was over open water. Polish Defense Minister Mariusz Blaszczak posted a proud Twitter message saying that the American B-52 had been escorted by Polish fighter jets.

Read more on the Nordic counntries

Nordic disunion

Although the adversarial posturing and rhetoric are reasons for concern, the likelihood of an open military confrontation between Russia and NATO remains low. The downside for Russia is that so much of its land forces have been destroyed in Ukraine. The losses notably include among the Arctic brigades. Both troops and special-purpose Arctic equipment from these units have been observed on the battlefields in Ukraine. The exact magnitude of their degradation is unclear but believed to be substantial. Although Arctic bases remain staffed by skeleton units, there can be little doubt that Russian military strength in the region has been degraded.

New strategic reality

This is occurring when Finland just has joined NATO, and Sweden is about to follow suit. The addition of the armed forces of these two countries – highly capable in winter warfare in mountainous terrain – makes short shrift of previous scenarios of a Russian push toward the west to reach the coast of Norway.

Russian military planners will now instead have to consider the danger of a NATO ground operation to take out the Russian bases on Kola at a time when its ground forces are fully committed in Ukraine. The long common Russian-Finnish border, and the fact that Finland has the most potent artillery force in Europe, constitute a particular threat to Russia’s northwestern flank. Yet, given that a NATO ground offensive would be sure to provoke a nuclear response, this is not a likely scenario.

What does remain as a threat against NATO in the north is the fact that Russian naval forces remain largely intact. The nuclear ballistic missile submarines present a severe strategic challenge, and modern Kilo-class conventional submarines are not to be trifled with. Russia also has smaller surface ships like the Gorshkov-class frigates that offer capable platforms for launching cruise and anti-ship missiles. The Russian Air Force is also believed to be largely intact. Mostly absent from Ukrainian airspace, it has sustained minor losses only – at least in comparison to the ground forces.

Russian brinkmanship expected

Discounting the danger of a ground war in the Arctic, the question that remains concerns just how combat-capable the Russian naval and air assets are. Military analysts have already been proven fundamentally wrong in their assessments of the capability of the Russian ground forces. The fact that the Russian air force failed to achieve air superiority in Ukraine, and has since been mainly withheld from combat, does say something meaningful about its capability.

As Russia realizes it is losing the war in Ukraine, it will likely seek to save face by engaging in brinkmanship elsewhere.

The prior media hype about advanced Russian missile technology has taken an even bigger hit. It is not enough that the stocks of some of the more advanced missiles have been seriously depleted. Their accuracy has already proven to be poor, and as planners dig deeper into old stockpiles, reliability will deteriorate even further.

If the Russian military command were to contemplate getting into a shooting war with NATO, it would have to consider that indiscriminate bombing of civilian targets in Ukraine offers a very different challenge from engaging technologically advanced NATO forces that possess effective countermeasures, including long-range precision strike capabilities that have been denied the Ukrainian defenders.

While the danger of Russia deliberately initiating a large-scale armed conflict in the Arctic may, in consequence, be viewed as slim to nonexistent, there remains a danger of close encounters that may result in serious escalation. The incident with a Russian fighter jet downing a U.S. reconnaissance drone over the Black Sea in March brings that message home.

The leading cause for concern is that as Russia realizes it is losing the war in Ukraine, it will likely seek to save face by engaging in brinkmanship elsewhere. Given its location and its increasingly important role as a supplier of gas to the European Union, Norway offers a tempting target for deniable Russian intelligence and sabotage actions.

The waters off its long coastline offer soft targets that range from drilling platforms to pipelines and assorted underwater cables. The sabotage against the Nord Stream pipelines illustrates vulnerability, and there have been mounting indications of Russian ambitions to scout and chart such assets. Following numerous incidents of drones flying close to critical installations on land, members of the Norwegian Home Guard have also been called up to patrol and protect such potential targets.

Scenarios

Protracted standoff

The baseline scenario has the Arctic as an important arena for a protracted standoff between Russia and NATO. Having already secured superiority on land, the U.S. and its allies will deploy substantial air and naval assets to intimidate and counter Russian moves. General Secretary Jens Stoltenberg has also vowed that NATO assets stand ready to protect Norwegian offshore energy infrastructure for as long as it takes.

China’s risky game

As Arctic cooperation becomes increasingly focused against Russia, China’s ambition to secure its own Arctic interests gives it added incentive to seek a settlement of the war in Ukraine. If this succeeds, it will bring good news for developing the Northern Sea Route and Chinese participation in Arctic resource exploration. However, Russia risks triggering even more economic sanctions as it attempts to bolster its bargaining position with the military. Unwilling to ditch its Russian friend, the Middle Kingdom may end up on the losing side in Ukraine and the Arctic.