The outlook for Russia’s navy

The Russian Navy is trying to overcome its reputation as “more rust than ready” by becoming capable of force projection. The money and plans for new ships are there, but modernizing its “legacy ships” will be more difficult.

In a nutshell

- Russia is dedicating a huge amount of money for a naval buildup

- Ostensibly, the aim is to make the Russian Navy a blue-water power

- It cannot succeed in competing with the U.S. and China for force projection

- It will, however, become even more effective at defending the homeland

Long derided as “more rust than ready,” the Russian Navy is attempting a comeback. The admiralty envisions a “blue-water navy” that is capable of force projection far from the home shores. Military industries delight in a huge flow of funds for naval construction and the Kremlin is integrating naval power into its foreign policy.

At a mid-May meeting with military and defense industry leaders in the Black Sea resort city of Sochi, Russian President Vladimir Putin praised the navy’s role in enforcing the country’s interests abroad and announced that naval assets would remain on station near Syria. “Our ships armed with Kalibr cruise missiles will be on a constant military watch,” he said.

Several countries have deployed naval assets to Syria since the onset of the crisis there. Both surface ships and submarines have been used as platforms for missile launches. In the words of United States Navy Admiral James G. Foggo III, the head of NATO’s naval and southern commands, the arrival of Russian warships and submarines has left the eastern Mediterranean “very crowded.”

Skillful game

The real reason why the increased presence of the Russian Navy (and its very silent submarines) gives NATO cause for concern goes beyond Syria. The big prize for the Kremlin is increased influence in the Middle East, where it has played a highly skillful game of forging alliances and balancing interests.

As the crisis surrounding Iran heats up, the Persian Gulf will grow in importance. With Russia also looking at an enhanced role in Libya, it is natural that the Kremlin is searching for ways to pair its diplomacy with military muscle. Geography dictates that this will have to include naval assets, and the core question is whether its navy is ready to deliver. At first glance, the answer would seem to be yes.

The Black Sea Fleet has coped with the complex logistics involved in sustaining the Syrian air campaign.

During the Syria operation, the Russian Black Sea Fleet has proven that earlier rumors of its imminent demise were premature. It has coped with the complex logistics involved in sustaining the air campaign. In July 2015, it established a 15-ship Mediterranean Task Force, based at the leased naval facility at Tartus. Other ships have since been rotated in from the Northern Fleet. This means the Mediterranean is no longer a “NATO Lake,” owned by the U.S. 6th Fleet.

Blue water

Looking beyond Syria, at stake is whether the Kremlin will succeed in building a genuine blue-water navy. The money is there. The State Armament Program for 2011-2020 gives lavishly to a naval buildup. By 2020, 54 new ships are to be commissioned, ranging from large oceangoing surface combatants to smaller coastal vessels and submarines (both nuclear and conventional).

Russia’s vision of restored naval grandeur includes the construction of new aircraft carriers. “Project Shtorm” envisions the building of three such ships, one each for the Northern and the Pacific Fleets, and one to be undergoing maintenance. At 100,000 tons, they would rival the U.S. supercarriers.

From a military strategic point of view, there is some logic in this vision. With an air wing of 90 aircraft on board, a single modern U.S. carrier houses more aviation than the individual air forces of most countries in the world. This is the ultimate tool of power projection, and it has been the mainstay of U.S. naval doctrine for decades.

China has started building its third carrier, viewing it as essential to its force projection into the South China Sea. The United Kingdom and India will soon have two each, and even Thailand has one. It is understandable that Russia wants to remain in this club.

New ships

The list of other large surface ships to be built includes a new Lider (Leader) class of nuclear- propelled destroyers. At 17,500 tons, these ships would bridge the gap to the massive Kirov-class battle cruisers, and they would carry a more potent missile armament than any other warship. Like the carriers, however, they will likely remain a vision only.

The Admiral Gorshkov-class guided missile frigate is a different story. The first blue-water vessel built since the end of the Cold War, it is equipped with a 16-cell vertical launch system that can fire Kalibr land-attack cruise missiles, supersonic P-800 Oniks over-the-horizon anti-ship missiles and 91RTE2 anti-submarine missiles. It also carries torpedoes, a 130-millimeter naval gun and the Pantsir air-defense system. Two of these ships have been built, and three more may be added.

Facts & figures

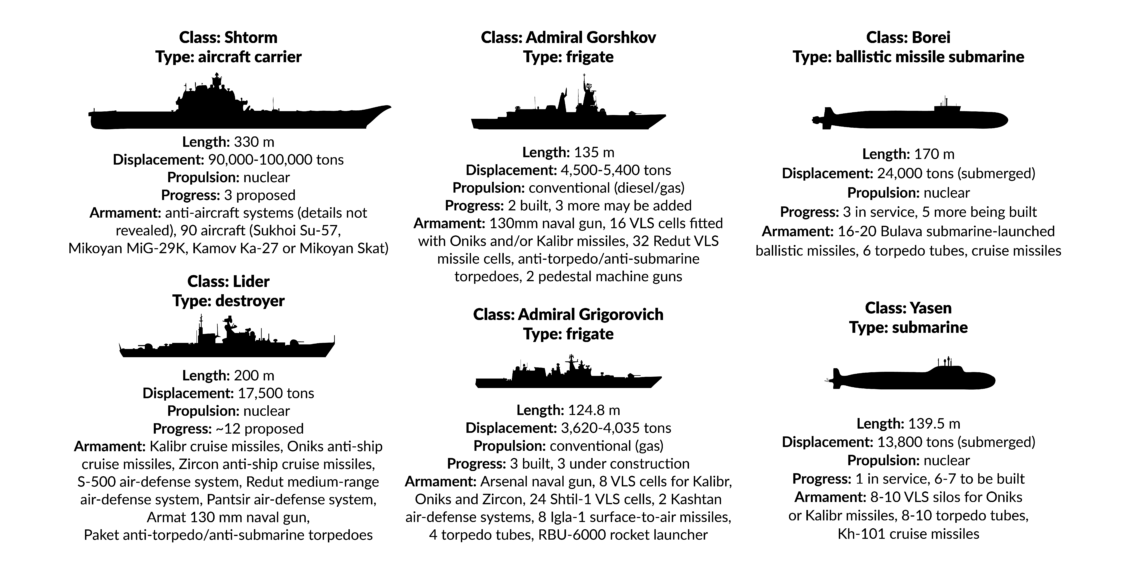

Key new Russian Navy vessels

Under the State Armament Program for 2011-2020, 54 new ships are to be commissioned

A smaller version, with less potent armament, is the Admiral Grigorovich-class guided missile frigate. Three have been built and more are on the way.

The armament program also includes new submarines. Three of the new Borei-class strategic nuclear ballistic submarines have already entered service, carrying 16 Bulava submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs), with a range of 9,000 kilometers. The next five in the class may carry 20 Bulavas.

Nuclear deterrence will be further enhanced by the new Yasen-class nuclear-powered attack submarines. Armed with torpedoes and cruise missiles, it is reported to be the quietest yet in a long line of advanced designs. Although only six or seven will be built, they represent a potent additional threat to the U.S. homeland. A single Yasen lurking in the Atlantic could deliver a salvo of 32 Kalibr cruise missiles with nuclear warheads to the east coast.

Legacy ships

Add to this a program of overhaul and modernization of existing assets, and it looks as though Russia may be about to enter the race with China and the U.S. for naval power projection. The key to understanding the prospects for that to come true lies in the notion of “legacy ships.”

Russia currently has around 270 warships on the books. Of these, only 125 are in reasonable working order and only 45 are oceangoing surface ships and submarines that are in good condition and deployable. It is a sobering fact that having been built for a 25-year service life, the majority of Russia’s naval vessels are presently aged well over 20 years. They will soon either have to undergo renovation or be retired.

The Black Sea Fleet is a case in point. Of its 45 surface ships, the only ones built after 1990 are three Admiral Grigorovich-class frigates. The fleet flagship, the guided missile cruiser Moskva, dates back to 1983. A guided missile destroyer, the Smetlivy, dates to 1969, and two guided missile frigates were built in 1980 and 1981. This is what has given rise to the epithet “more rust than ready.”

The Kremlin’s ambition to reclaim great power status hinges on whether the ‘legacy ships’ can be modernized.

The Kremlin’s ambition to reclaim the status of a great power hinges largely on whether the “legacy ships” can be modernized. The prospects for this are dimmed by the performance of Russian naval shipbuilding, which is the worst by far of any military industry. The Russian admiralty has been embarrassed by its inability to spend the funds allocated under the current armament program.

The war with Ukraine has added trouble by severing links to subcontractors. A prominent example is gas turbines for the new frigates. Two Gorshkov-class and three Grigorovich-class frigates were equipped with turbines delivered before the war. Building the remainder has been set back at least five years, as a Russian manufacturer is being phased in.

Land power

Despite these constraints, the new naval doctrine recently announced by President Putin still promotes a vision of a revived Russian Navy that can maintain superiority over China and even stand up to the U.S. Navy. Both are iffy propositions.

The U.S. Navy has 290 warships, all of which are oceangoing, well-maintained and deployable. Under the Trump administration, more ships will be added, widening the gulf between Russian and U.S. capabilities. The very idea of Russia competing with this naval superiority simply cannot be taken seriously. Even the notion of remaining stronger than the rapidly expanding Chinese Navy appears a tall order, especially since financing for military shipbuilding is likely to decline in the next decade.

A realistic assessment of the Russian Navy’s prospects must start from the fact that in contrast to the U.S. and the UK, both of which have long naval traditions, Russia is a land power. The Soviet Navy was never intended to compete with NATO on offense. Its mission was to defend the Motherland, by making sure that any incursion into home waters would be extremely costly.

The Kirov-class heavy battle cruisers were built for precisely this purpose – to conduct anti-submarine warfare and to take on U.S. carrier groups. Their main weapon was 20 P-700 Granit (SS-N-19 Shipwreck) anti-ship cruise missiles mounted in the deck. The launch of the Kirov-class project was a big reason behind U.S. President Ronald Reagan’s decision to recommission the Iowa-class battleships.

Several of the new ships Russia is building could give NATO cause for concern, but others – like the Lider-class destroyers – are unlikely to ever be built.

Once the bluster is peeled away, the goal of the current Russian naval buildup remains very much the same – to make any attempt by the U.S. and its allies to attack the Motherland very costly. This is to be achieved by wagering on advanced missile technology and a range of small and versatile missile-launching platforms, from corvettes and frigates to very silent attack submarines.

Carriers

The Soviet Union did have ambitions to develop a blue-water navy. By the time the USSR collapsed, the Soviet Navy had seven carriers on the books: two Moskva-class helicopter carriers, four Kiev-class nuclear anti-submarine cruisers, and one true fixed-wing carrier, the Admiral Kuznetsov. But the Moskva and Kiev ships were either sold or scrapped in the 1990s. Today, only the Kuznetsov remains.

The sad fate of this ship, launched in 1985, signals the end of Russian carrier warfare. In November 2016, it was deployed from the Northern Fleet to the Mediterranean, to support the air campaign in Syria. The carrier’s fault propulsion system required it to be accompanied by an oceangoing tug and made simply getting to the Mediterranean and back an achievement. While on station, it lost two aircraft in noncombat accidents; its aircraft were then forced to operate from bases on land. The Kuznetsov will soon be withdrawn from service for an extensive refit, resulting in a loss of continuity and training in carrier operations.

Adding the cancellation of the French Mistral-class helicopter assault ships that were destined for the Pacific Fleet, it follows that Russia’s vision of acquiring a blue-water navy is not based on reality. No combat ships larger than a frigate have been built since the 1990s, and none are likely to be completed in the next 10 years. There will be no carriers, nor any Lider-class destroyers, nor any focus on the massive amphibious assault ships that were designed to support a Soviet invasion of Europe.

Of the Soviet era’s large oceangoing surface vessels, all that remains is the Pyotr Velikiy, the last of the Kirov-class battle cruisers. The first two ships in the class are beyond repair. A third, the Admiral Nakhimov, has been modernized and will soon rejoin the Northern Fleet. When it does, the Pyotr Velikiy will be retired for a similar overhaul. When it returns, Russia will have two oceangoing surface ships that can show the flag for political purposes. But this has little to do with real force projection. Simply sustaining operations in Syria already represents considerable overstretch.

Primary missions

The primary missions of the Russian Navy remain nuclear deterrence and coastal defense, both of which are being credibly performed. The nuclear submarines are highly capable, and the modernized Kilo-class conventional submarines are so silent that they are known in NATO circles as “black holes.” The wager on corvettes and frigates as platforms for advanced high-precision weaponry in all spheres of naval warfare also appears to have been successful.

Combined with equally potent land-based Bastion anti-ship missiles and S-400 air defense systems, these advances ensure that, in the words of an American military analyst, anyone contemplating an assault on the Motherland had better bring plenty of life rafts.