Russia’s import substitution: Effects and consequences

With its ability to import industrial and high-tech goods constricted since 2014, Russia has implemented an ambitious “import-substitution” strategy to protect its economy. The policies have had mixed results, to put it mildly.

In a nutshell

- Russia has made it a national security matter to reduce its dependency on imports

- Its ‘import substitution’ has worked better in the food sector than industrial ones

- Russia's share in the global economy has been shrinking

In 2014, the European Union, the United States and several other countries imposed sanctions on Russia in response to its actions in Ukraine. The sanctions targeted individuals and sectors of the economy, blocking investments and supplies of high-tech products to Russia and restricting its access to foreign financing. These measures remain in effect, and new restrictions have been added since.

In response, Russia decided to introduce what it called “counter-sanctions.” On August 6, 2014, the president of Russia issued a decree “On the application of certain special economic measures to ensure the security of the Russian Federation.” In effect, the regulation embargoed the imports to Russia of “certain types” of agricultural products, raw materials and food that originated in the countries that had imposed the sanctions against Russian citizens or legal entities.

Russia strikes back

The Russian government immediately followed up, making the embargoes’ content specific: it applied to meat, fish, dairy products, vegetables, fruits and nuts. The ban remains in effect.

The country considers its dependence on imports a national security matter.

The Western sanctions blocked the supply of several categories of high-tech products to Russia, including those necessary for the raw material export industries and the military-industrial complex. In response, the government initiated an “import substitution” program, establishing in early 2015 a special commission to implement it. A reduction in the country’s dependence on imports began to be considered in the context of national security.

So, what have been the results of the “import substitution” policies?

Food

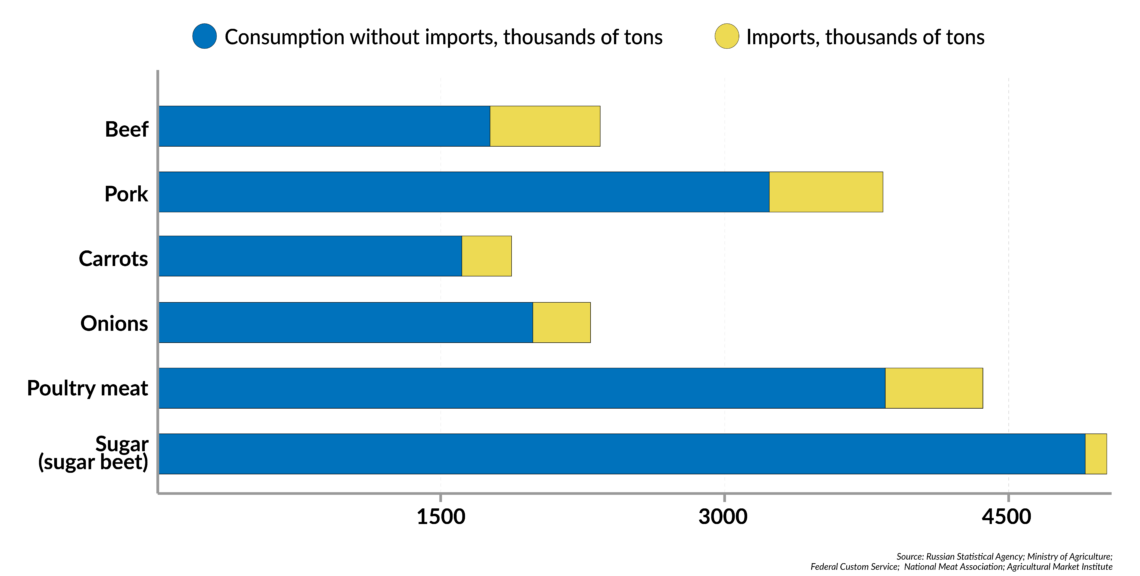

The first chart shows the ratio of imports in staple food consumption in Russia; the pre-sanctions year 2013 is the departure point.

Facts & figures

The share of imports in food consumption in 2013

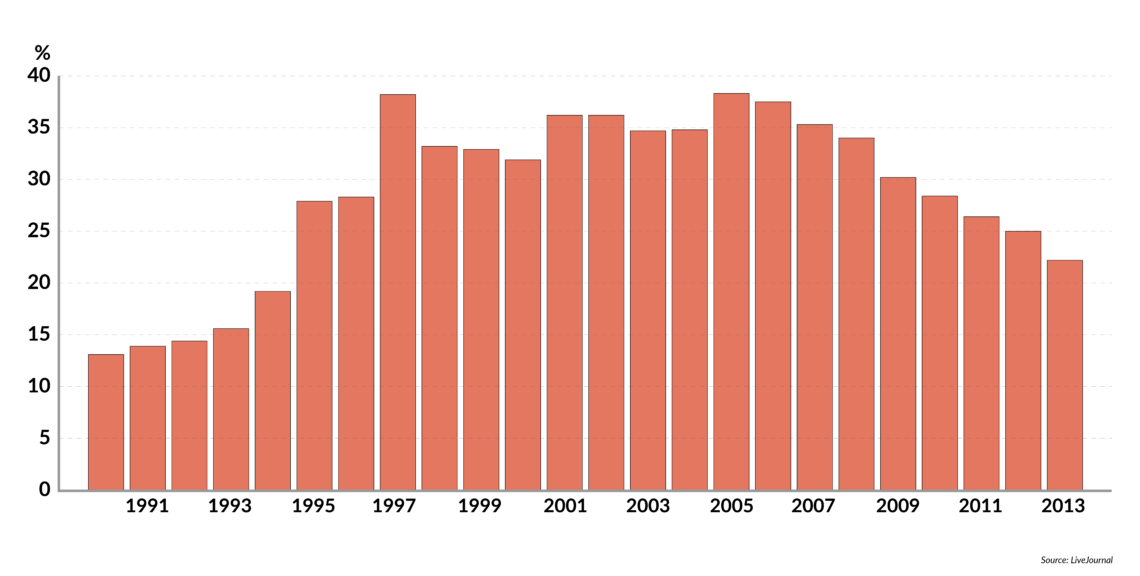

The share of imports in Russia’s meat consumption had been declining rapidly since 2005.

Facts & figures

Shares of imports in meat and meat products, 1990-2013, %

The share of imports in Russia’s meat consumption had been declining rapidly since 2005.

Facts & figures

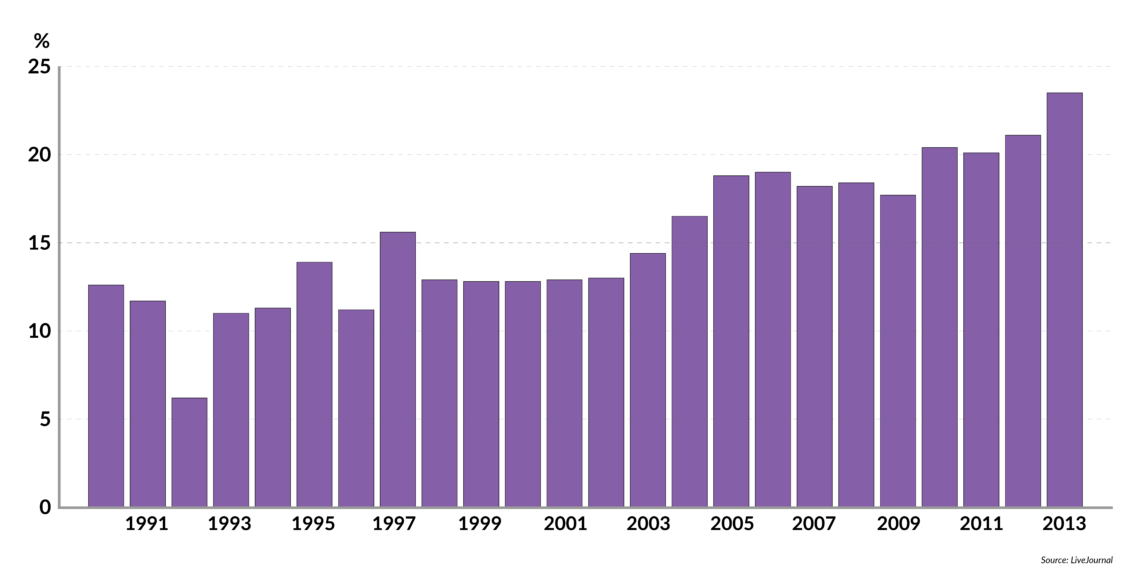

Shares of imports in milk and dairy products, 1990-2013, %

That decline was due to Russia’s ramping up of domestic meat production, primarily pork and chicken. However, the situation regarding milk and dairy products evolved in the opposite direction; the industry was clearly in crisis.How has the domestic production of meat and milk, as well as meat and dairy products, changed over several years of import substitution?

From 2013 to 2019, the growth in meat and meat products amounted to 34 percent. The production of milk during the same period stayed at roughly the same level. Cheesemaking was ramped up by 24 percent (imports of this food were practically prohibited), and fermented milk products rose by 11 percent (except for sour cream and cottage cheese).

As a result, the share of imports in Russia’s meat resources fell to 6 percent by 2019, and in dairy resources – to 16 percent. The same trend is observed for all major types of food. The share of imported food products in retail trade dropped from 34 percent in 2013 to 25 percent in 2019. At the same time, the consumption of essential food products by families either has not changed or even increased.

Thus, in general, the provision of food to the population remains stable despite the sanctions and anti-sanctions imposed by Russia. Two factors explain this. First was the overall growth of the country’s agricultural sector and agro-industrial complex; this development began even before the sanctions against Russia. In 2011-2019, gross agricultural output (in current prices) increased almost 2.4 times. The second factor has been the elimination of market competition from imported goods.

Russia’s share in the global economy has been shrinking.

At the same time, some negative consequences from the introduction of Russia’s embargo on food imports from selected countries have manifested themselves: a discernible reduction in the variety of goods available in retail, especially in the premium goods sector, and price increases that can be attributed to diminished market competition.

However, one can say that Russian’s import substitution policies for food have proven largely successful.

High-tech goods

Let us start with the medicines. In 2013, the share of imports in the pharmaceutical market of Russia was 68 percent; in 2019, it dropped to 50 percent. This reduction in import dependency resulted from the decisions by major international pharmaceutical companies – Novartis AG, Pfizer Inc., Teva Ltd., AstraZeneca plc, and others – to open production facilities in Russia. At the same time, Russia remains heavily dependent on the imports of components necessary for making medicines. Russian companies produce no more than 15 percent of the required agents.

Another critical area is information technology. It has not been possible to eliminate foreign goods here – Russia still imports more IT products than it exports. Domestic production is not well developed and for some imported goods there are no Russian substitutes. However, domestically developed software is now the leader in public procurement and already accounts for more than half of its volume. In reality, however, state bodies often pretend not to notice that the hardware delivered is imported, with Russian labels glued on the boxes, and they may be asked to pay for crudely customized, free-of-charge Western software pretending to be a domestically made product.

And talking of industry, despite all the brouhaha over import substitution, the share of machinery and equipment in the commodity structure of imports has practically not changed: in 2013 and 2019, it was the same 30 percent.

According to a survey of heads of industrial enterprises conducted quarterly by one of Russia’s leading think tanks, the Gaidar Institute of Economic Policy, in 2015, 30 percent of enterprises in their purchasing were replacing imports of machinery and equipment with domestic goods, and 22 percent replaced raw materials and materials. By the fall of 2018, the share of such enterprises, active in both areas of import substitution, decreased to 8-9 percent, after which monitoring was discontinued.

“The main obstacle to import substitution remains the lack of production on the territory of the Russian Federation of the necessary equipment, components and raw materials for enterprises,” noted the Gaidar Institute. Another problem was “the low quality of domestic products.”

From 2013 to 2018, significant progress in import substitution (concerning equipment) occurred only in metallurgical engineering – it was gauged at 8.8 percent. To a lesser extent, the indicator registered changes also in agrochemistry and production of equipment for construction and mining.

Meanwhile, in some other areas, dependence on imports increased. Most of all, in the processing of vegetables and fruits (by 12 percent) and the production of general-purpose equipment (by 11.2 percent).

“There has been practically no progress in terms of import substitution in recent years,” we read in the materials of the Center for Macroeconomic Analysis and Short-term Forecasting, a body close to the Russian government.

The outcome

It has become clear that political decisions imposing import substitution on the Russian economy, adopted after the introduction of the Western sanctions in 2014, have had only limited success. The main reasons for this state of affairs are:

- The insufficient size of the Russian economy: it is too small to produce all the necessary goods for development. Moreover, Russia’s share in the global economy has been shrinking. In 2008, it was 3.68 percent, but the figure has decreased constantly; by the end of 2020, it stood at 3.075 percent. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) forecasts, this negative trend will continue in the coming years. At present, Russia’s gross domestic product (GDP), adjusted for purchasing power parity, is almost six times smaller than China’s, five times smaller than the U. S.’s, and more than twice smaller than India’s

- Low labor productivity: according to the IMF, Russia ranked 51 in the world in 2020 in terms of GDP (purchasing power parity)

- Second-rate substitutes: Russian substitutes for imported goods cannot compete with the originals in price or quality. The success of the import substitution strategy does not hinge only on the availability of any substitutes for imported goods. Russian industrial goods exports depend heavily on imported high-quality production equipment, which is more efficient than Russian-made machines and allows manufacturers to save on costs

- The outflow of capital. This restricts investment in the creation of quality and modern domestic production. In 2020 alone, $47.8 billion in capital left Russia. This was 2.1 times more than the 2019 figure

Scenarios

In these circumstances, the Russian authorities face two basic options for going forward.

The first option is to continue the policy of import substitution at all costs. For the reasons listed above, this will further degrade the Russian economy, making its structure even cruder. The existing profile of Russian exports, with its heavy focus on energy and raw materials, will be preserved, leading to severe risks related to the energy transition in developed countries and China. This scenario opens the door to dire economic consequences for Russia, including a 10 percent decline in Russia's GDP by the 2030s – as Anatoly Chubais, President Vladimir Putin's special representative for sustainable development, publicly stated. At the same time, the population’s real incomes may fall by as much as 14 percent, according to Herman Gref, the head of Sberbank PJSC, Russia’s largest lender. The Russian government will likely move toward more oppressive governance to maintain internal political stability in such dire circumstances.

The second option would be to change Russia’s foreign economic policy course away from autarchy and toward openness and international cooperation. Such a shift – unlikely to take place without a change of the country's leadership – would necessitate a liberalizing overhaul of all the country’s key institutions – both the political and economic spheres. It is impossible, of course, to predict when such changes may occur. The only thing that seems certain right now is that a fundamental shift is necessary and, therefore, inevitable.