Russian airpower on trial

Russia’s air force has come a long way from its inept performance during the 2008 war with Georgia. In terms of control and command, logistics, and sortie rates during its campaign in Syria, it has far surpassed expectations. But that tells us about how it would stack up against a sophisticated enemy, especially against the U.S. Air Force.

In a nutshell

- Russia’s air operations in Syria show much better logistics and command capabilities

- Yet this improvement has come against an enemy without sophisticated air defenses

- In key technologies like stealth or precision guidance, Russia still lags behind the U.S.

Ten years have passed since Russia went to war with Georgia, a conflict that brought its armed forces victory through overwhelming numbers but also humiliation from their abysmal performance against a vastly weaker enemy. Over the past decade, the Russian leadership has responded with a determined and well-financed effort to reform and modernize its military.

One of the main beneficiaries has been the Russian Air Force, which has acquired hundreds of new aircraft, some of them highly sophisticated. If this buildup continues for another decade, as forecast, Russia will field a modern fleet of 1,100-1,200 tactical aircraft and close to 200 long-range bombers by 2027.

The present transitional phase in this modernization program has left many outside observers bewildered. While some have expressed apprehension that Russia is about to become a formidable menace even to NATO, others insist that the potential threat is mostly smoke and mirrors.

Then and now

The key question is whether Russia’s rising number of modern aircraft is being accompanied by upgrades in avionics and weapons systems needed to place their capabilities on par with its main potential adversary, the United States Air Force. A first approximation can be reached by comparing the Russian Air Force’s performance during the Syrian intervention with its track record during the August 2008 war with Georgia.

During the Georgian campaign, which lasted a mere five days, Russian aviation flew perhaps 200 missions, with seven aircraft shot down (including one Tu-22 bomber) and four damaged, implying a loss rate of 5.5 percent (or one loss per 18 combat missions). In Syria, Russia has conducted an intensive, three-year air campaign while suffering minimal losses (two fixed-wing aircraft shot down by hostile fire, five lost to accidents).

The Syrian campaign has exposed Russian pilots and ground crews to challenges not seen since the Afghan war.

The Russian Air Force has proved beyond a doubt its ability to conduct a sustained expeditionary air campaign far from home. Its logistical performance has been impressive, far exceeding expectations, as large quantities of fuel and munitions were airlifted to the combat zone along with bulkier items like helicopters and air-defense batteries.

Russian President Vladimir Putin has every reason to be pleased. When the intervention was launched in September 2015, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s regime was faced with defeat against multiple enemies. Three years later, it has emerged on top, allowing the Kremlin to triumphantly announce that Europe may begin repatriating its Syrian refugees.

On-the-job training

Russia has thus added a formidable instrument to its foreign policy toolbox. While this is bad news for smaller powers that might be subjected to expeditionary assaults, it does not necessarily mean the Russian Air Force is about to emerge as a serious rival to United States airpower. A closer look at the Syrian intervention provides mixed answers to this question.

There is no doubt that Syria has been a valuable training exercise. Russian pilots and ground crews have faced challenges not seen since the Afghan war. While the number of aircraft committed has been small, the rate of combat sorties has been impressively high, averaging 50-60 per day, with peaks well above 100.

This performance has been achieved by assigning two aircrews per aircraft and deploying more ground technicians than the norm, including specialists from manufacturers qualified to conduct both maintenance and upgrades. While it says little about how Russian air units would fare in a hypothetical conflict with NATO, it is a useful guide to their likely effectiveness in future expeditionary scenarios.

Combined arms operations have improved dramatically, but against a virtually defenseless enemy.

The biggest improvement has been combined arms operations, which failed spectacularly in the Georgia war. During the Syrian campaign, operational headquarters have successfully coordinated air and naval operations with those on the ground, while providing close air support to friendly Syrian and Iranian forces. Commanders have also adroitly managed “deconfliction,” liaising with their U.S. and Israeli counterparts to avoid close encounters with Western coalition aircraft.

The downside is that these successful operations have been against a virtually defenseless enemy. Because the Russian Air Force has aggressively rotated pilots (a practice dating back to the Korean and Arab-Israeli wars), the Syrian operation has given some 80 percent of its tactical aviation crews and 95 percent of army aviation helicopter crews the opportunity to fly in combat conditions. But this says little about exactly what they have been learning.

Combat lessons

The first takeaway is that the Russian bombing campaign left the heavy lifting to older designs like the Su-24 Fencer and the Su-25 Frogfoot, which date back to the 1970s. The initial deployment of 32 aircraft to Syria included 12 Su-25SMs and 12 Su-24Ms. The balance was made up of four modern Su-30SM Flanker-H multirole fighters and four Su-34 Fullback bombers.

The operation expanded in November 2015, when the Kremlin decided to take revenge on ISIS for the terrorist attack on a Russian Metrojet airliner in Egypt. By reinforcing the initial expeditionary force with 37 Su-27 and Su-34 aircraft, Russian air units temporarily increased the daily sortie rate to 127. This total included flights by Russia-based strategic aviation. A force of five Tu-160, six Tu-95MS and 14 Tu-22M3 long-range bombers flew 6,500 km to launch 16 of the new Kh-101 and several of the older Kh-555 cruise missiles against ISIS targets in Raqqa. These cruise missiles had never been used in combat. Even so, until the spring of 2017, about half of all combat sorties in Syria were conducted by the obsolescent Su-24M.

A second distinguishing feature of Russian air operations in Syria is that attacks have been carried out from altitudes above 5,000 meters, to minimize the risk of being shot down by ground fire. This implies that the precision of these attacks is very low.

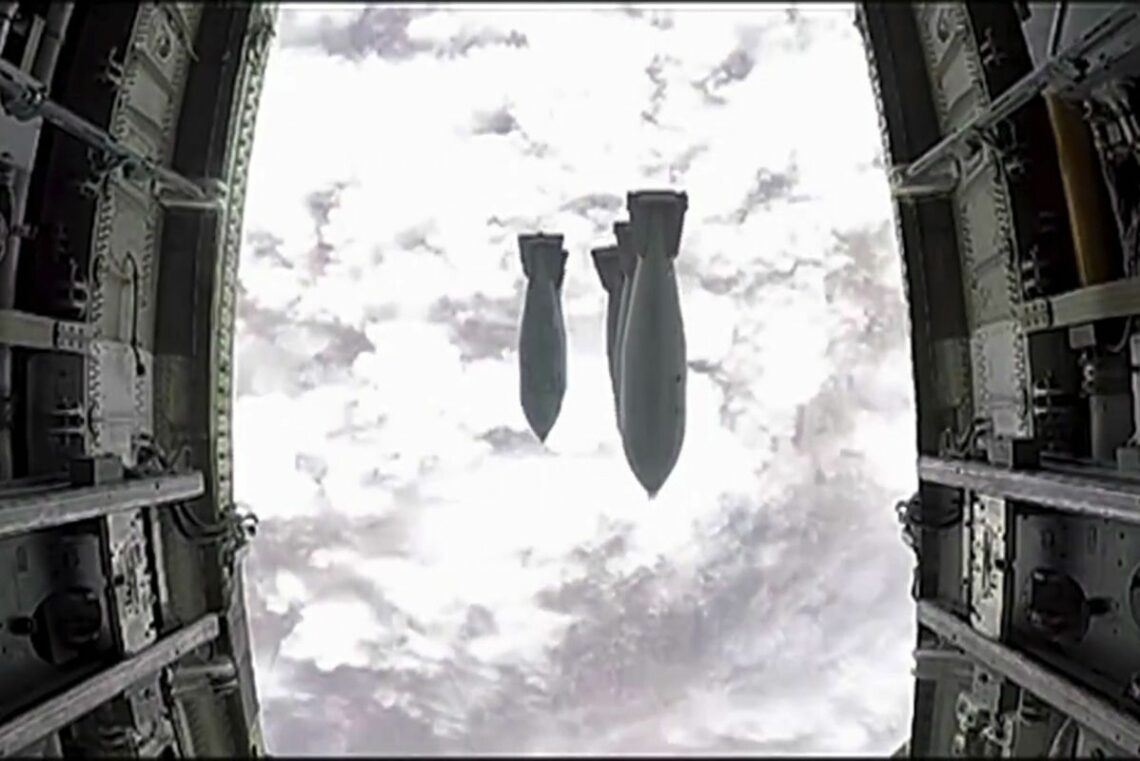

The Syrian intervention did mark the first time that Russian aviation has used precision-guided munitions (PGMs). But the share of “smart” weapons has been only about one-fifth of the tonnage dropped. The rest has been made up of “dumb” bombs of 1980s vintage. While this practice may be viewed as cost-effective, Russian aircraft conspicuously lack the targeting pods routinely fitted to U.S. aircraft to guide PGMs.

Russia has developed its own version of the old U.S. JDAM (Joint Direct Attack Munition) guidance kit that relies on GPS satellite navigation to transform old iron bombs into smart weapons. Known as SVP-24, it is dependent on the Russian GLONASS system, which is less accurate than the GPS. Since the accuracy of American JDAM munitions in Iraq fell well short of the media hype, the precision of their Russian counterparts in Syria must be poor indeed.

In short, Russia’s air campaign in Syria has succeeded mainly because outdated aircraft have dropped large loads of high-explosive and fragmentation bombs on unprotected civilians. While this has sufficed to achieve victory, it has been contingent on a callous attitude to civilian casualties. It could well be true that Russian air attacks are responsible for more civilian deaths than either ISIS or the Syrian Arab Army (SAA). By using the same type of ordnance as Syrian aircraft, however, Russian forces have achieved plausible deniability.

What the Syrian operations do not show is how Russia would fare in an air campaign more sensitive to collateral damage and waged against sophisticated defenses. The February 2018 downing of an Su-25 by rebels in Idlib province may be significant here, as it was a rare instance of Russian ground-attack aircraft encountering modern, shoulder-fired surface-to-air missiles, or MANPADs.

The story with army aviation has been different. Attack helicopters like the iconic Mi-24 Hind, and newer models like the Mi-28, Mi-35 and Ka-52, have been highly effective at providing close air support. In return, however, they have suffered a much higher loss rate than fixed-wing aircraft.

Air superiority

A real test of how Russian airpower stacks up against its American rivals lies in the use of tactical aviation to achieve air superiority. Here the U.S. F-16 Fighting Falcon and F-15 Strike Eagle would be matched against modern variants of the classic Su-27, including the two-seat Su-30SM Flanker and the single-seat Su-35S Flanker-E.

While the latter models have flown in Syria, they have been used purely for ground attack, not aerial combat. The only time Russian aircraft have encountered hostile fire in the air was in November 2015, when a Turkish F-16 shot down a Russian Su-24 that had briefly strayed into Turkish airspace.

The decisive factors in combat are radar and long-range target acquisition, where the U.S. retains an edge.

By sharing the same airspace with advanced U.S. designs such as the F-22 Raptor, Russian pilots have been able to practice radar and target acquisition. Still, that leaves open the question of whether they could hope to achieve air superiority.

Some have argued that the Su-30SM Flanker would outperform an F-15 Strike Eagle in a dogfight. But such aerobatics are mainly for show, not for a modern air war. The pilot of an aircraft that ends up in a dogfight has probably already made serious mistakes. The decisive factors in combat are radar and long-range target acquisition, in which the U.S. is believed to retain an edge.

Demonstration effect

The cutting edge in future air combat is likely to be fifth-generation stealth fighters. The U.S. has been operating stealth aircraft for more than 30 years, coming of age with the iconic F-117 Nighthawk that led the way in the invasion of Iraq. Today it has more than 387 such aircraft, including 187 F-22 Raptors and about 200 F-35 Lightning II Joint Strike Fighters.

Russia is still experimenting. Sukhoi has long been working on a prototype known as the T-50 PAK-FA. Recently renamed Su-57, only 10 are believed to have been built. The Su-57 caused quite a stir when four of these prototype aircraft were sighted in Syria. Since their value in combat operations would have been slim indeed, the obvious purpose was a propaganda stunt.

The Kremlin’s willingness to expose such expensive aircraft to the risk of being destroyed on the ground, by random mortar or drone attacks, demonstrates the value it places on the demonstration effect of showing that it, too, can operate stealth aircraft in combat. This ambition has permeated the Syrian campaign, which has provided opportunities for testing – and showcasing – new weapons.

The main objective of the cruise missile strikes by long-range bombers, corvettes in the Caspian Sea and submarines in the Mediterranean was to signal NATO that Russia has developed a formidable standoff missile capability. In response, NATO has begun thinking seriously about killer drones and long-range artillery.

Keeping score

The ambition to intimidate NATO fits in with Russia’s strategic objectives of deterrence and protecting the Motherland. Modern missile technology, including sophisticated air defense systems like the S-400, is not to be taken lightly as a way of achieving these aims.

The air campaign in Syria must be assessed in this context. While it enhances Russia’s ability to intimidate smaller nations, it need not impress NATO. Nor has the indiscriminate bombing of defenseless civilian targets helped to market Russian military technology.

Having tactical aviation drop PGMs using inferior GLONASS technology merely drives home that Russia lacks effective precision-guided, air-launched standoff missiles like the Raytheon AGM-154. Even the brief appearance of the Su-57 served mainly to demonstrate that Russia is not really in the game of stealth.

Russian arms producers are threatened on export markets where customers demand more sophisticated equipment.

In this light, two developments this year seem significant. In April, India finally decided to pull out of an 11-year partnership to develop the T-50 stealth fighter. At about the same time, Russia’s plans to build a stealthy long-range bomber, the Tupolev PAK-DA, were quietly shelved. Claims that Russia has developed radars that make stealth irrelevant do not impress. If Russian arms producers want to remain serious players in export markets where customers are demanding more sophisticated equipment, this is not good enough.

What remains is Russia’s undisputed air defense capability, which is more than adequate to deter attacks against the Motherland. Just as assessments of Russia’s naval capabilities must ignore talk about building a blue-water navy, with carriers and heavy missile destroyers, and focus on protecting home shores with advanced missile platforms, analysis of Russian airpower must distinguish between its ability to conduct foreign operations and to defend its own airspace.

On the latter count, Russia merits respect. NATO sources have even expressed concern that Norwegian aviation could be grounded by Russia’s anti-access area denial (A2/AD) capability. As missile technology supersedes conventional aviation, focusing on tactical aircraft and dogfighting skills might be keeping score in the wrong game.