Italian gold and populist publicity

Italy’s Deputy Prime Minister Matteo Salvini has revived a proposal to use his country’s gold reserves to reduce the budget deficit. Mr. Salvini is likely using this controversial plan to make headlines and burnish his populist credentials.

In a nutshell

- Matteo Salvini’s proposal to sell Italian gold to finance the deficit is unworkable

- Pushing the idea does, however, further several of his political goals

- Mr. Salvini is likely trying to take center stage in European politics

In early February, Matteo Salvini, Italy’s deputy prime minister and leader of the Lega party (formerly the Northern League), opened a debate on whether the country’s gold reserves could be used for fiscal policymaking. He floated the idea of selling the gold for euros to finance the budget deficit and cut – or slow down the rise in – public indebtedness.

As often happens in Italian politics, one has the impression that making headlines is more important than thinking twice: Mr. Salvini merely mentioned the need to avoid a rise in the value-added tax (VAT) to finance public expenditure and suggested that selling some of the country’s gold reserves could serve the purpose. He offered no further analysis. When journalists asked him to detail the proposal, Mr. Salvini added that he had not really “studied” the possibility, but that he would do so in the future. Moreover, with a daring leap of logic, he added that Italy’s gold reserves belong to all Italians.

Does tampering with Italy’s gold reserves make any sense? In this report, we analyze the basic facts and offer views on what might happen next, as well as about what to make of Mr. Salvini’s half-baked proposal.

Changing the rules

The situation is not as simple as Mr. Salvini seems to believe. The large quantities of gold ingots with “Italy” stamped on them do not belong to the country’s residents or to the Italian government, but rather to the Bank of Italy, which has strong links with the state but remains an independent entity owned by a set of commercial banks and insurance companies. The top two shareholders are the big Italian commercial banks – Intesa Sanpaolo and Unicredit. Together they own more than 28 percent of shares in the central bank. Moreover, some of the gold has been transferred to the European Central Bank to support the Eurosystem and is currently considered as a loan to Frankfurt.

Mr. Salvini and Lega are reviving a proposal put forward more than five years ago.

Mr. Salvini and Lega are actually reviving a proposal put forward more than five years ago by the former leader of the leftist Five Star Movement (M5S), Beppe Grillo. It involves expropriating the Bank of Italy, perhaps by passing a constitutional law to that effect, and asking the ECB to return at least a portion of the loan.

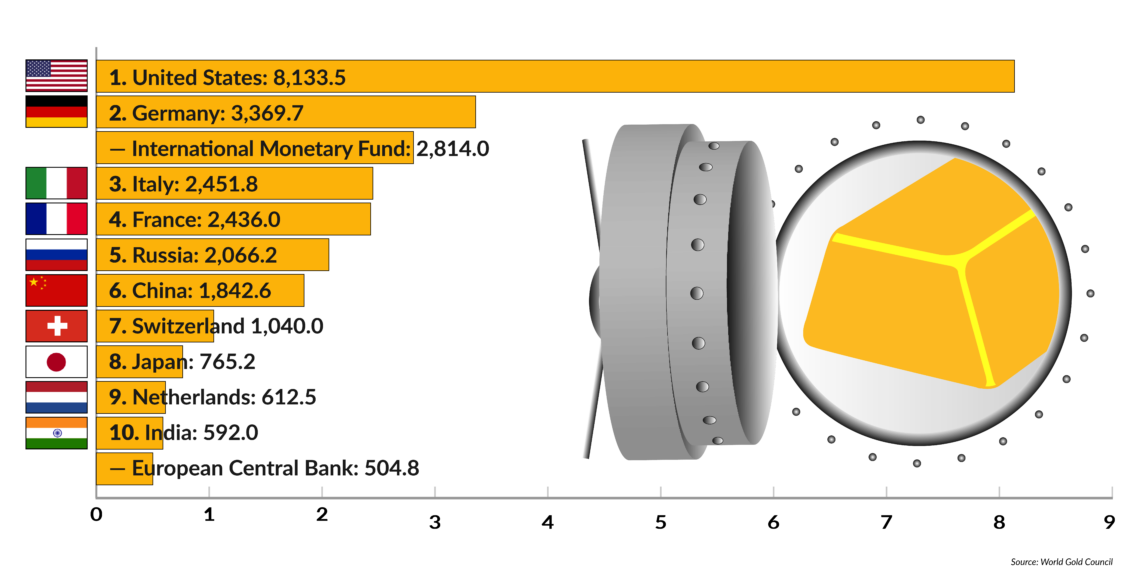

The booty would be substantial and badly needed. Italian gold reserves amount to some 2,450 tons, worth nearly 90 billion euros. They are the fourth-largest in the world (after the United States Federal Reserve, Germany’s Bundesbank and the International Monetary Fund). If the Italian budget deficit violates the 2.04 percent limit agreed upon with European authorities last December, the Italian government would be forced to increase the VAT rate in 2020 and again in 2021, generating additional budget revenues of 20 billion euros and 12 billion euros, respectively. Italy would be able to hide the deficit and avoid the VAT rise by selling between 30 percent and 50 percent of its gold reserves, depending on the price of gold and the size of the deficit. Of course, these sales would cover the budgetary needs for two years and have nothing to do with structural adjustment.

To follow up on Mr. Grillo’s earlier idea, Lega would have to change the rules of the game within the Eurosystem and withdraw its gold deposit with the ECB; or quit the euro altogether. Constitutional changes would also be needed to appropriate the Bank of Italy’s gold, requiring the government to secure a two-thirds majority in parliament.

If Mr. Salvini persists with his idea and the government follows up on it, the Italian authorities would proceed on two parallel tracks: negotiating with the ECB while working to amend Italy’s constitution.

Populist bravado

We believe that Mr. Salvini and his supporters will not make much progress with Frankfurt and Brussels. European central banking is done by European central bankers, and one can easily imagine their reluctance to allow politicians to tarnish their prestige and empty their vaults. It is true that in most eurozone member countries, gold belongs to the “state,” rather than to the central bankers. In this aspect, Italy is an outlier.

Facts & figures

All that glitters

Largest gold reserves (metric tons held)

Yet, Frankfurt might take advantage of the debate and clarify that gold should be considered as collateral for present and future euros in circulation. In other words, the ECB might dig in and fight back, arguing that the Italian anomaly should become the rule, not the exception, and that it should be transformed into a Eurosystem regulation.

Would this be enough to discourage Lega and stifle Mr. Salvini’s effort to study the matter? Not necessarily. Lega’s grip on economics (let alone M5S’s) is rather fragile. Searching its economic policy for a consistent strategy aimed at reshaping Italy’s public expenditure and the European Union’s entire monetary architecture is futile.

For example, a year ago Lega was clearly against the euro and manifestly hostile to the EU, but it now claims that quitting the euro is out of the question and has quietly bowed to the budgetary winds blowing from Brussels. However, Mr. Salvini’s success (according to the polls, over 35 percent of Italians support Lega) is based on displays of populist bravado, rather than on grand strategies. Immigration was, until recently, the pièce de résistance of his repertoire. The gold proposal could take the spotlight and improve his party’s political performance by triggering a debate on the role of European central banking, possibly expanding to EU-directed fiscal policy.

Mr. Salvini is trying to take center stage in Europe and lead a broad euroskeptic alliance.

We posit that Mr. Salvini is trying to take center stage in Europe and lead a broad euroskeptic alliance in the new European Parliament. In doing so, he would kill several birds with one stone. He would divert Italians’ attention from their domestic problems and claim he is reshaping the EU, destroying the allegedly nefarious Franco-German alliance and restoring Italy as a major player in European affairs. In the meantime, he would still be able to blame Europe for all of Italy’s misfortunes, including any recessions. (M5S would become the next scapegoat.) And he would, of course, serve his vanity and ambition. Mr. Salvini’s attempt to change the role of gold within the EU economy might fail miserably, but this is a relatively minor point.

Four options

If this scenario materializes, Mr. Salvini will face a dilemma at home. Will he engage in a constitutional fight over Italy’s gold reserves, and ultimately try to nationalize the Italian central bank? Or will he downplay the domestic issues and turn his energies abroad? Four lines of action seem possible.

In the first, Mr. Salvini would act on the European stage to stake his claim to leadership of the euroskeptic alliance after May’s EU parliamentary elections. As a second option, he would try to reform monetary and fiscal policies at the national and EU levels. Financing Italian expenditure through gold sales would be just the first step. The second would include radically transforming the ECB and its relationship with the central banks of each EU member state.

The third possibility is radically different and would boil down to using the gold pretext to weaken and possibly delegitimize the Bank of Italy, which has recently been very critical of the government’s economic policy. Tensions with Frankfurt would be incidental and short-lived.

Finally, a fourth possibility would be to foment tensions with and within M5S, forcing it to abandon the coalition and triggering new elections before the end of this year.

It is hard to say which option will prevail. Lega lives one day to the next, while waiting for M5S to collapse. Mr. Salvini has no interest in pursuing technical matters that he has not mastered and that might eventually marginalize Italy in Europe.

In this light, we predict that the proposal to sell Italian gold will be shelved after a brief flurry of publicity. After all, Mr. Salvini himself later specified that he did not really mean what the journalists had understood him to say. Yet, populist leaders are unpredictable. If the gold turns out to be a winning issue for Lega, it might stay with us for months to come.