Sailing in the dark

With forecasts for oil demand and supply highly discouraging, Saudi Arabia enforces strict production caps compliance among OPEC members, warns financial markets “speculators” against betting on falling prices and hints at the possibility of further output cuts.

In a nutshell

- Oil prices have returned to their June average

- Saudi Arabia enforces strict production caps

- OPEC’s production cuts may prove insufficient to push up prices

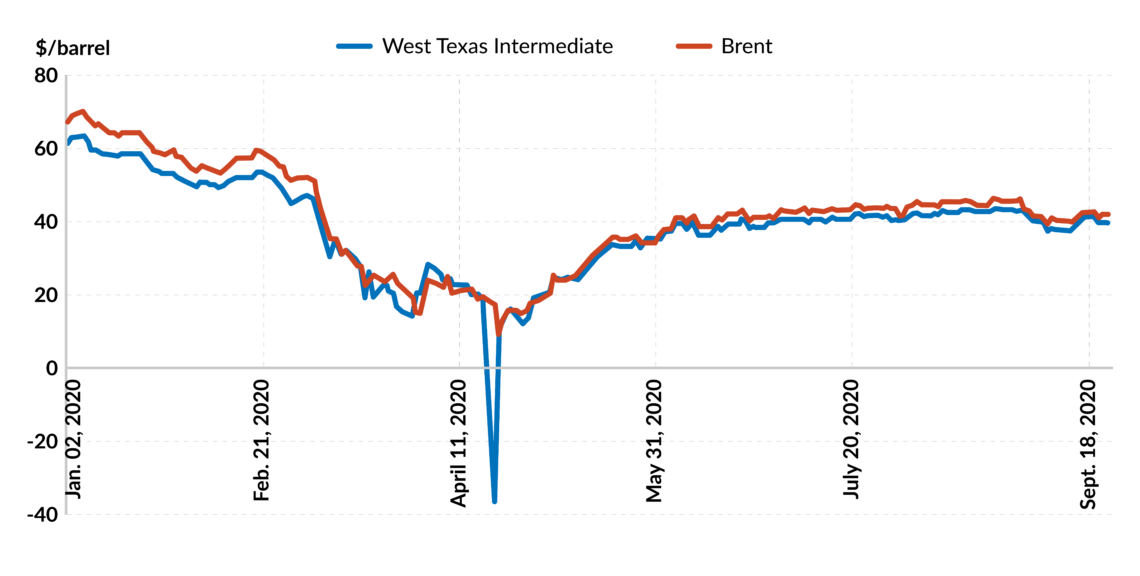

Having stalled through June and July, the recovery of the global oil market seemed to reboot in August. The OPEC+ producer alliance stuck to its schedule and relaxed its cuts by 2 million barrels per day, stating that “momentum” was in their “favor.” The optimism, however, was short-lived. After briefly crossing the $46 per barrel (bbl) mark in August, Brent oil prices fell below $39/bbl two weeks later and have hovered around $41/bbl ever since, with West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude at around $39/bbl – bringing prices back in line with their average since June. According to the September edition of the Dallas Fed Energy Survey, oil and gas producers expect a WTI oil price of around $43/bbl by the end of 2020.

As a result, OPEC’s tone has changed. After the group’s latest Joint Ministerial Monitoring Committee meeting in early September, the group’s tone went from confident to swaggering. OPEC’s most influential minister, Saudi Arabia’s Energy Minister Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman Al Saud openly warned financial market “speculators” against betting on falling prices. At the same time, however, the organization has shown its noncomplying members more leniency.

Facts & figures

OPEC +’s deployed immense efforts to initiate upward pressure on prices with cuts of a historic magnitude, but offsetting forces are still proving stronger. Forecasts for both the economy and oil demand are revised all the time, but the fact remains that as long as there is no effective treatment or vaccine for the coronavirus, everyone will continue to sail in the dark.

Facts & figures

OPEC membership

- OPEC was created in 1960 by Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Venezuela. Over the years, its membership has changed.

- Currently, it comprises 13 countries: Algeria, Angola, Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Libya, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Venezuela.

- Long-term members Indonesia, Qatar, and Ecuador left the organization in 2018, 2019 and 2020 respectively, while Equatorial Guinea and Congo became the latest countries to join the group in 2017 and 2018, respectively.

Happy birthday

OPEC celebrated its 60th anniversary this year. One cannot but admire the organization’s ability to survive and remain relevant despite the perennial problems arising from the twin challenges of cheating members and serious political divisions.

Saudi Arabia deserves most of the credit for the longevity of the organization. The world’s largest oil exporter has pursued a quiet behind-the-scenes oil policy. It often subsidized noncompliant OPEC members. On other occasions – like the “price war” in March 2020 – the Saudis opened the spigots and allowed oil prices to collapse, restoring discipline within the group. For the time being, however, and as long as Covid-19 continues to cast its long shadow on the global economy, Saudi Arabia has to deal with the compliance problem, to ensure production caps are recognised across the board.

OPEC’s stance toward noncompliant members has hardened compared to pre-pandemic times.

While reversing the Covid-19 oil price collapse, OPEC’s stance toward noncompliant members has indeed hardened compared to pre-pandemic times. In June, the organization announced a compensation scheme for the first time: members who did not restrain their output as much as agreed in May and June had to cut the “underperformed volumes in July, August and September.” At the September meeting, in a small nod to acknowledge sluggish compliance, that deadline was extended until the end of the year.

However, OPEC’s overall compliance in August has improved to a very respectable 97 percent (up from 94 percent in July). For once, reality may be better than the numbers suggest because a very unusual suspect has emerged as the principal offender: the United Arab Emirates’ compliance decreased from 97 percent to 74 percent. The UAE is a crucial and reliable OPEC member and this violation (caused by a need to produce more natural gas as a by-product of oil) is likely a quirk that will be corrected quickly.

Meanwhile, OPEC’s partners in the broader OPEC+ deal – nine countries led by Russia – have proven to be equally committed to the joint agreement, with a compliance rate of 98 percent. On the back of its strong performance, OPEC has hinted at the possibility of deepening the cuts in the coming months, should oil demand remain sluggish. Unfortunately, in today’s oil markets, this strategy may only aggravate the organization’s challenges.

More supply troubles

The reason lies in the potential recovery of further supplies – from within OPEC and outside the group. Within OPEC, additional barrels from Libya are expected to hit the market. Libyan warlord General Khalifa Haftar, head of the self-styled Libyan National Army whose troops blocked Libya’s oil ports in January, announced the blockade’s end in September. It is unclear how much additional oil will reach international markets; Libya’s production has been on a roller coaster since 2010, but under current circumstances, even a small increase spells trouble for OPEC+.

Moreover, the United States’ presidential election could change U.S. policy toward Iran if Democrat Joe Biden wins the race. Both Iran and Libya are OPEC members exempted from the cuts because of the social and economic hardship they endure (caused by sanctions and civil war). Under both scenarios, the rest of OPEC would have to curtail their output further.

Outside OPEC, the problem is that the moderate price increase accomplished thus far gives rise to more oil deliveries from private producers, particularly in the U.S. shale patch. According to the Dallas Fed Energy Survey, published in September, the contraction’s pace in the U.S. oil and gas sector has significantly lessened.

According to the Dallas Fed Energy Survey, the contraction’s pace in the U.S. oil and gas sector has lessened.

There has been a lively debate on whether the record levels of U.S. shale oil production seen before the pandemic will ever be reached again. The answer depends on two factors: oil demand, which affects prices, and the ability of shale producers to improve efficiency by cutting costs. The production does not depend on the availability of shale resources, which are plentiful. One should not underestimate the private sector’s creativity in a competitive oil market (as is the rule in the U.S.). After all, the incentive structure provided by competition moves the technological frontiers in any industry. Even if former vice president Joe Biden wins the elections, his administration is unlikely to hurt the shale industry, which has given the U.S. strong leverage in foreign affairs.

Some commentators have taken the wave of bankruptcies that have accompanied the recent financial restructuring in the shale industry as a harbinger of its imminent demise. Such a conclusion is likely to prove false. The U.S. is very efficient when it comes to keeping the assets of bankrupt companies in operation. It is simply not legitimate to calculate these enterprises’ cumulative value and conclude that the industry must be “dead.” The U.S. bankruptcy procedures allow for rapid restoration of an industry by facilitating the fast transfer of the assets of insolvent (and often inefficient) producers into the hands of investors and new owners, typically with more capital. This system triggers better performance after the restructuring.

Historically, the outcome of financial restructuring has been stronger, not weaker, performance, also in the shale industry. There is no apparent reason why this time, things could be different. A more productive shale industry will react even more swiftly, increasing production in response to the rise in price generated by OPEC caps from Saudi Arabia.

Peak oil demand?

The most critical force dictating the direction of the oil market remains the demand for the commodity. It will determine how fast, or slow, the record-high inventory built during the coronavirus lockdown can be brought back to average levels – the precondition for restoring a market balance with durable price increases.

In the final analysis, the global economy’s health will continue to set the pace of the oil demand recovery. Although improvements are expected in the third quarter of 2020, they will be uneven and low-base, and unlikely to imply a sharp V-shaped recovery – especially not as long as Covid-19 infections continue to spread at the current rapid pace.

Oil demand remains much less understood than oil supply.

At some point, the world will get over this dark phase. What happens next is a matter of how much of the demand destruction caused by the pandemic proves structural – and hence irretrievable, regardless of economic recovery. BP’s annual energy outlook published in September presents two scenarios in which demand never recovers to pre-Covid levels. Oil demand peaked in 2019, states the report. For one of the large international oil and gas companies, this is a significant reassessment: last year, BP, along with its peers, expected oil demand to peak in the 2030s, or even later.

Scenarios

In reality, no one knows when this will occur. Oil demand remains much less understood than oil supply. However, it may well be that the Covid-19 crisis has brought us closer to its peak. Oil intensity – the amount of oil used to produce one unit of GDP – has been on a declining trend since the first oil shock in 1973. These efficiency improvements are likely to continue even in times of weak demand.

A recent study confirms what has been long known: for decades, global demand for crude oil has been growing. However, this growth rate has slowed – sometimes in response to an energy crisis, in other cases, due to structural changes in economic activity. Most importantly, oil intensity does not recover to precrisis levels after a major crisis, even after many years. Efficiency improvements are here to stay.

Should oil demand peak, the oil industry will no longer be able to free ride on OPEC, and OPEC itself will no longer be able to pursue its long-standing practice of cutting production to raise prices. In a shrinking market, such a strategy will simply result in the worst possible outcome: a smaller market share and lower revenues.

Prince Abdulaziz Al Saud, Saudi Arabia’s energy minister, recently stated: “[W]e will never leave this market unattended.” Whatever he means by that, OPEC in general and Saudi Arabia in particular have their work cut out for them: once the pandemic is over, oil producers can only hope for a short breathing period before the next battle.