Senegal on the path to authoritarianism

When a popular opposition politician was arrested on rape charges, Senegal erupted into protests. More and more young citizens resent the ruling elite. This growing dissent may prompt the government to adopt an increasingly authoritarian stance.

In a nutshell

- Antiestablishment sentiment is on the rise in Senegal

- Authorities have responded with strict measures

- Protests will not necessarily result in a regime change

The mass protests in Senegal resulted from three distinct trends shaping politics in sub-Saharan Africa: the rise of authoritarianism, increasing political and social tensions among the young, urban and jobless population, and the emergence of popular (and populist) leaders in street politics and social media.

Senegalese exception

In a region plagued by political instability, Senegal has had two democratic and peaceful transfers of power and no coups since achieving independence in 1960. According to the Ibrahim Index of African Governance, despite a slight downward trend, the country still ranks 9 out of 54 countries in overall governance and 10 when it comes to participation, rights, and inclusion.

However, more and more voices claim that Senegal is becoming increasingly authoritarian amid growing social and economic discontent. To understand these claims, it is necessary to go back to the presidency of Abdoulaye Wade (2000-2012). Mr. Wade defeated the hegemonic Parti Socialiste by mobilizing opposition parties through a coalition campaigning for “Sopi” (meaning “change” in Wolof).

During President Macky Sall’s first term, Senegal was one of the fastest-growing economies in Africa.

But his popularity significantly decreased during his second term, as he attempted to run for a third mandate through constitutional engineering. In the second round of the 2012 presidential elections, he was defeated by Macky Sall, no outsider to Senegalese politics. He had previously acted as minister of mining and energy; interior minister; prime minister, and president of the national assembly. In 2008, he left the Parti Democratique Senegalais (PDS) and formed the Alliance for the Republic (APR).

During President Sall’s first term, Senegal was one of the fastest-growing economies in Africa, with annual rates exceeding 5 percent. This period was characterized by the expansion of infrastructures and socioeconomic improvements, through the implementation of the ambitious Plan Senegal Emergent (PSE). However, these successes were accompanied by a few political setbacks.

First, the electoral law was changed in a way that limits political competition. Second, ambiguous constitutional amendments were approved in a referendum in 2016. Whereas the presidential term length was reduced from seven to five years, the Constitutional Council ruled that the reduction did not apply to the incumbent, who had come to power in 2012 and would be allowed to stay in office until 2019. Third, the presidential candidates of the two main parties were excluded from the 2019 elections because they had been convicted in corruption cases in which justice may have been instrumentalized for political ends. Fourth, in a surprising move in November 2020, President Sall dissolved the government to form a new executive, coopting members of opposition parties. Idrissa Seck, who came second in the 2019 presidential elections, was made chair of the country’s economic and social council.

More recently, the national assembly passed two anti-terrorism bills which, according to the opposition, may be used to prevent legitimate manifestations of political discontent. Their vague definition of “seriously disturbing public order,” for example, means a broad range of actions could be considered “act[s] of terrorism”.

Neutralizing the opposition through the judicialization of politics and the cooptation of its more vocal and prominent members is an old tactic, common to semi-authoritarian and authoritarian regimes in Africa and beyond, from Zimbabwe to Venezuela.

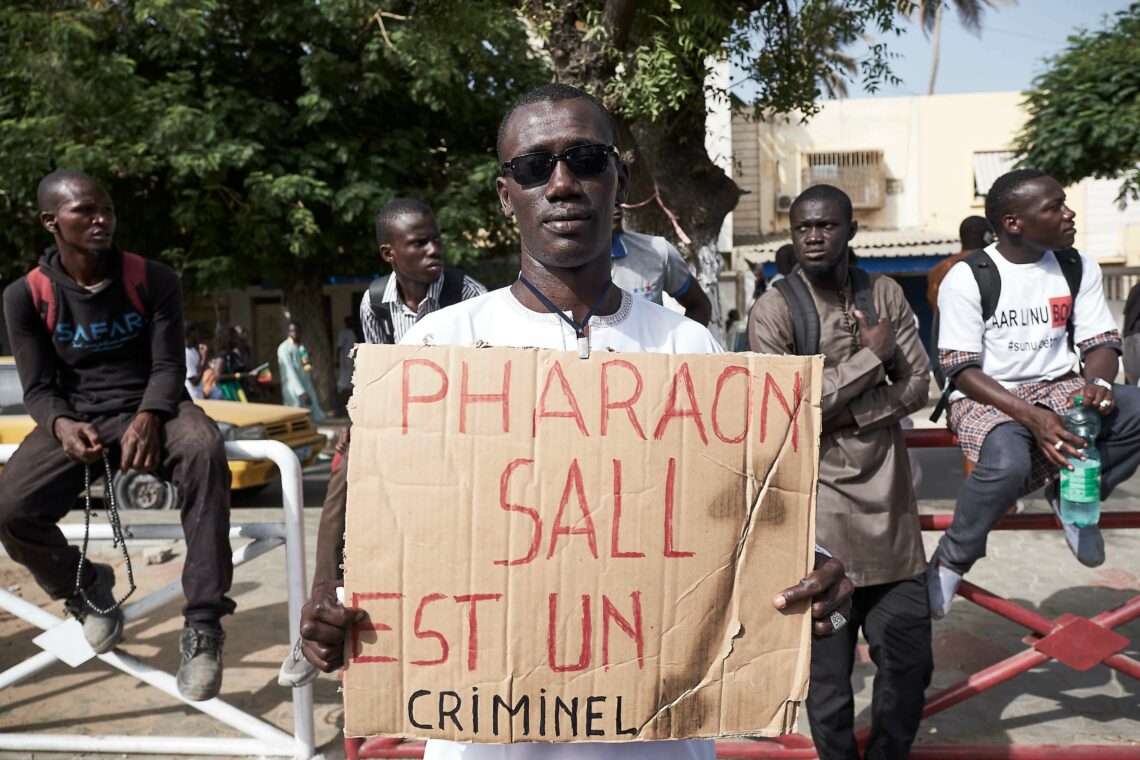

Mass protests

In March, mass protests were triggered by the imprisonment of Ousmane Sonko, a member of parliament. A fierce critic of the ruling elite and leader of the party PASTEF (Patriots of Senegal for Ethics, Work and Fraternity), he had come third in the 2019 elections. Violent demonstrations erupted while he was being taken to a police station after having been accused of raping a woman at a massage parlor. His parliamentary immunity was revoked, and he was charged with disrupting the public order and placed in custody.

Ousmane Sonko and his party denounce corruption and the establishment, decrying “neocolonialism” and “neo-imperialism” – including the country’s alleged subservience to France and adherence to Islam. Like Bobi Wine, who emerged as a challenger to President Yoweri Museveni in Uganda, Mr. Sonko is increasingly popular among the young, urban population. Given his sometimes inflammatory rhetoric and anti-system stance, he can be considered a populist politician.

Like in Uganda, Nigeria and Angola, the recent protests were marked by violent clashes between protesters and security forces. As a result, President Sall has announced new legislative initiatives to regulate (and restrict) social media, which were instrumental in mobilizing the population.

Socioeconomic fragility

Senegal benefits from significant advantages when compared with other countries in the region, including better health indicators, electricity and safe water access, internet penetration rates and gross domestic product (GDP) growth. However, the robust economic improvements of the last few years were not sufficient to keep pace with a fast-growing, young and increasingly urban population.

When it comes to critical indicators for a services-led growth strategy, such as expected mean years of schooling (the average number of completed years of education of a country’s population aged 25 years and older, excluding years spent repeating individual grades), Senegal ranks lower than African countries like Uganda, Nigeria, Tanzania, Togo, Djibouti, Rwanda or Ivory Coast. In 2019, 60 percent of the country’s 16.3 million population was under the age of 25. According to data from the UNFPA, in 2011, 36 percent of the girls and 37.5 percent of the boys aged 10-14 were out of school, and in 2015 the proportion of youth (15-24) not in education, employment or training was 28.7 percent among males and 42.8 among females. Adult and youth literacy rates remain low.

Because of the high unemployment rate, more and more young Senegalese are trying to reach Europe.

This fragile outlook has been dramatically affected by the economic consequences of the measures imposed to contain Covid-19. Restrictions mainly affected the informal sector, the primary source of income for most young people. Although President Sall recently announced the implementation of a $637 million-emergency program for employment and socioeconomic integration of the youth, this may be too little, too late. Because of the high unemployment rate, more and more young Senegalese are trying to reach Europe.

Scenarios

Events in Senegal reflect broader trends in sub-Saharan Africa. As seen in other countries in the region, a particular grievance – in this case, Mr. Sonko’s detention – triggered large-scale and violent protests reflecting the growing frustration of certain segments of the population.

Under a first, most likely scenario, while other waves of protests may emerge, President Sall will remain in power until the end of his term in 2024. Uncertainty and political violence, however, will likely increase as of 2023. Economic issues will determine election results. Under this scenario of relative stability, thanks to competitive production costs, security, and capacity to attract foreign investment, Senegal may benefit from a fast economic recovery. However, even under the best circumstances, youth unemployment will remain high.

The electoral contest will pave the way for three different outcomes. The most likely result is that President Sall’s political successor will win the elections because of post-Covid recovery dynamics, the competitive advantages of incumbents and the awareness among regional and international actors that such an outcome would preserve political stability.

Although less likely, elections could also lead to a protracted political and social crisis or the victory of Ousmane Sonko, considering his popularity among segments of the electorate and the fact that the most prominent figures of the opposition have either been neutralized or co-opted. These two scenarios would affect economic growth and reforms, not least because a critical competitive advantage of the Senegalese economy is the country’s reputation as one of the most stable democracies in the region.

Under another, less likely scenario, the country would go through a political crisis ahead of the 2024 elections. Such a crisis could be triggered by reactions to Mr. Sonko’s possible condemnation, which would prevent him from contesting the presidential election. President Sall could also attempt to run for a third time by claiming that the constitutional referendum reset the counter on his own term limit.

In this case, the president would face unprecedented protests. In similar circumstances, massive demonstrations have successfully removed other presidents from power – for example, Blaise Campaore in Burkina Faso in 2014. However, recent events in Africa suggest that incumbents still hold significant advantages. Moreover, Mr. Sall’s regional leverage and international popularity could mitigate the effects of internal protests.

While his reelection for a third term would end the Senegalese exception, it would not be surprising given recent events. In the region, Ivory Coast President Alassane Ouattara and Guinean President Alpha Conde have recently managed to extend their tenure in power.

While continuity will most likely go hand in hand with the authoritarianization of the Senegalese regime, ongoing political instability would further deteriorate the country’s social and economic prospects, leading to higher levels of migration and possibly radicalizing the youth.