Shinzo Abe’s successors to face a nasty test of wills

The Chinese craft intrusions in the territorial waters and airspace of Japan’s Senkaku Islands put Tokyo in a quandary. The question marks over the reliability of Washington’s support for U.S. Asian allies further complicates the Japanese position.

In a nutshell

- China ratchets up its military pressure in both South and East China Seas

- Challenging Japan’s sovereignty of Senkaku Islands is a threat to regional stability

- At stake is the credibility of the U.S.-Japan alliance

The steady expansion of China’s military presence in the South China Sea has caused much international concern in recent years, and rightly so. However, the situation in another hotspot has also become alarming: in the adjacent East China Sea, around the Senkaku Islands between Taiwan and the Okinawa archipelago.

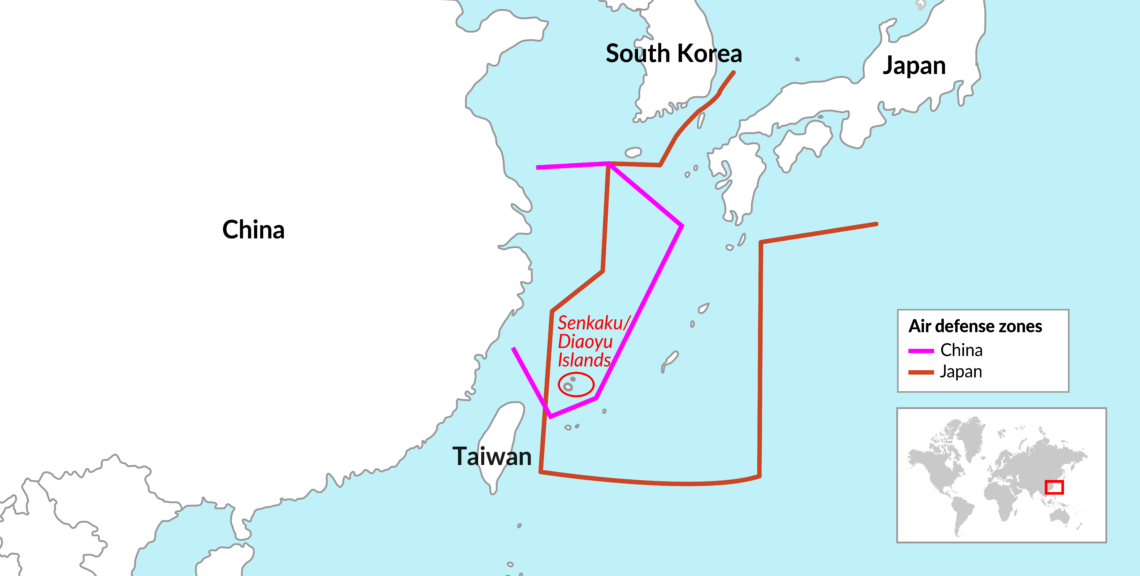

China, Taiwan and Japan claim these islands as their territory. Japan calls the uninhabited rocks the Senkaku Islands, the Chinese – the Diaoyu Islands. Japan controls the islands, but China’s craft are intruding into their territorial waters and airspace with increasing frequency.

The U.S. role

General Douglas MacArthur, the United States World War II commander in the Pacific theater, famously called Japan the “unsinkable aircraft carrier.” That carrier’s utility became fully evident during the Korean War (1950-1953). Today, the security environment in East Asia is chock-full of uncertainties, not least the ticking bomb in the north of the Korean Peninsula. The hermit regime in Pyongyang often leaves even China, its crucial supporter, at a loss about its goals while it pursues ballistic missile and nuclear warhead development programs.

Japan and South Korea have bilateral treaties with the U.S. and host significant American military bases. Seoul and Tokyo both know that the Americans’ protective umbrella is vital in preserving peace in the region and shielding their countries from aggressive Chinese designs. However, the foreign and security policy of the administration of President Donald Trump has created uncertainty among U.S. allies, not only in Europe and within NATO, but also in the Far East. Mr. Trump, however, has used less harsh language toward Japan than he has against Germany, in his recurrent criticism of bilateral trade deficits and insufficient contributions by allies to the common defense.

The Chinese navy undertook a massive display of its strength by conducting at the same time live-fire exercises in four areas.

While it was clear that the personal chemistry between Donald Trump and Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe was rather positive, abrupt mood swings at the White House have sowed much uncertainty. Many in the Far East wonder whether the American support would be fully available to allies on the brink of a hot war.

The question seems particularly pertinent concerning the Senkaku (or Diaoyu) Islands. Would the U.S. risk an exchange of blows with China to defend Japan’s control over a few uninhabited rocky islands in the East China Sea?

Facts & figures

Historical legacy

The Senkaku (in Chinese, Diaoyu) Islands are contested between Japan, the People’s Republic of China and the Republic of China (Taiwan). Historically, China has a strong claim.

- During the imperial Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), the Senkaku Islands were Chinese and have been shown as such on ancient maps. In 1895, Taiwan became a Japanese colony following China’s defeat in the first Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895)

- After the World War II capitulation of Japan in 1945, Taiwan returned to the Chinese Republic of Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek. The United States occupied Japan until its sovereignty was restored in 1953, under the Treaty of San Francisco

- However, Okinawa and the Senkaku Islands remained under American administration until 1972, when they were returned to Japan

- The United States held on to two island chains, Iwo Jima and Okinawa, on which it established significant military bases. In 1972, most of Okinawa was returned to Japanese sovereignty and the Senkaku Islands were handed over to the Japanese

- The Chinese have never accepted this state of affairs. The matter is of particular sensitivity to Beijing, as China had suffered massive war damages and humiliations under Japanese occupation

- Notably, nationalist circles in mainland China hold that the entire archipelago of Okinawa should be part of China, as in former times, when the islands were known as the Ryukyu Kingdom and the local rulers paid obeisance to the emperor in Beijing as early as in the 14th century

These worries have become more acute today, as the Chinese have increased their presence in the islands’ waters and air. In recent weeks, the Chinese navy undertook a massive display of its strength by conducting at the same time live-fire exercises in no fewer than four areas: the South China Sea, the East China Sea, the Yellow Sea and the Gulf of Bohai. This show of strength is directed at both the U.S. and Japan. Beijing’s message: China has the capacity to concurrently take on several adversaries at various points of conflict in different war theaters. This makes the dispute about the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands directly connected with the current tensions in the South China Sea.

With such an escalation in the Chinese military presence, the danger of an intended or accidental collision with the Japanese air or sea craft increases and the reliability of the U.S. alliance becomes even more pressing. The point is not lost on the Americans. In late July 2020, in Tokyo’s Yokota Air Base, Lt. General Kevin Schneider, Commander of the U.S. troops in Japan, stated at a press briefing: “The U.S. is hundred percent, absolutely steadfast in its commitment to help the government of Japan with the situation in the Senkakus. That is 365 days a year, 24 hours a day, seven days a week.”

These words from the military commander have also been directed to Beijing. Gen. Schneider’s unambiguous message fits the hardened rhetoric recently employed by U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and U.S. National Security Advisor Robert O’Brien when dealing with China.

Facts & figures

China’s naval buildup

The islands dispute is part of a broader geopolitical shift that is currently taking place in the Indo-Pacific region. Tokyo is faced with a multilayered challenge to its future standing as a first-rate power in the Far East.

When China emerged as the “factory of the world” and then as an economic superpower – pushing Japan to the second rank – there was little debate about the security implications. Generally, people in the industrialized West were relaxed about China’s rise. The opinion that the emergence of a major world power would, this time, be a peaceful process held sway in the Western corridors of power, the corporate headquarters and the media. The leadership in Beijing itself seemed to promote this confidence.

The pragmatism of China’s great reformer, paramount leader Deng Xiaoping (1978-1985), who admonished his countrymen not to go overboard in their national pride, was expected to be heeded by his successors. Mr. Deng’s prescription to “hide your strength and bide your time” guided the country seeking a peaceful rise.

The arrival of Mr. Xi, followed by his quick accumulation of an extraordinary amount of power, marked a turning point in China’s modern history.

Today, we have gained new insight into the true nature of China’s rise to the top in Asia. Xi Jinping became secretary-general of the Communist Party of China in November of 2012 and president of the People’s Republic of China in March of 2013. This was not an ordinary change of power, as had happened a decade earlier, when Jiang Zemin (1989-2002) handed the reins of the party to his successor Hu Jintao (2002-2012).

The arrival of Mr. Xi, followed by his quick accumulation of an extraordinary amount of power, marked a turning point in China’s modern history. From then on, the erstwhile Middle Kingdom was no longer simply an economic superpower. It has strived for the position of no less than a hegemon.

Hence the challenge Japan faces in the East China Sea. China, which historically had not much strength in the high seas, in recent years, has substantially increased the capacity of its navy.

Tightrope walk

From the hull-count perspective, China’s naval buildup has been impressive. However, to extend maritime power far from one’s shores, a country needs a true blue-water navy with technical and strategic skills and experience, which are neither easy nor quick to acquire. With these aspects factored in, Japan’s Maritime Self-Defense Force is still superior to the Chinese armada.

Japan is facing a tightrope walk in the years to come. On the one hand, the Chinese claim for the Diaoyu Islands is not going to go away and no compromise seems possible; and there is Japan’s imperative, too, to protect its sovereignty. Tokyo needs to develop a strategy for responding to the Chinese actions at sea without provoking Beijing into an exchange of blows.

There have been diverging opinions about China relations within Japan and its ruling Liberal Democratic Party.

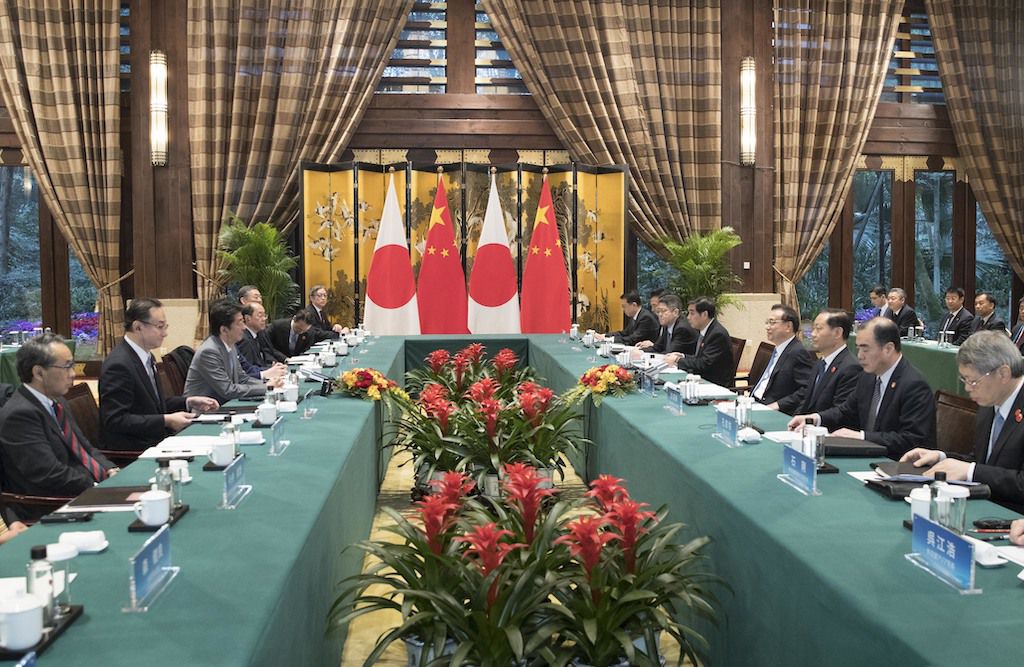

At present, the Japanese strategy is marked by ambivalence. Tokyo continues its conciliatory China policy in the face of the mounting provocations. During Mr. Abe’s watch (soon to end for health reasons), the two countries’ relations have improved. The planned April 2020 state visit by President Xi has been postponed due to Covid-19, but it has not been canceled.

Also, Japan has restrained its criticism of the new security law for Hong Kong. While international demands have mounted to censure Beijing over its violation of the former British colony’s liberties under the one country, two systems formula, Tokyo remains on the sideline.

Traditionally, there have been diverging opinions about China relations within Japan and its ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP). The hawks favor a harder line toward the Communist colossus. On the other side are those LDP members in Parliament and government who advocate a lenient approach, to remain on speaking terms with the Chinese leadership and stabilize bilateral relations through enhanced economic ties.

Prime Minister Abe has steered an ambivalent course. He has long been known as a nationalist, among those high-ranking Japanese politicians who irked the country’s neighbors by visiting the Shinto Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo, controversial for honoring some figures considered war criminals in the nations once occupied by Imperial Japan. However, in more recent times, and as prime minister, Mr. Abe sided with the LDP figures working for better relations with Beijing.

Scenarios

While the sudden resignation of a long-serving national leader of Mr. Abe’s caliber is bound to cause some apprehension, there is no need for alarm over his departure. As in Japan’s past, the transfer of power will be smooth. The state, the economy, and the social system put in place by the LDP are all sound. The world will hardly notice a change when a new prime minister takes charge.

Therefore, we foresee a scenario in which both Japan and China will muddle through the crisis. Japan is concerned about a more aggressive China. It will continue to discreetly build up its military power and enhance its geopolitical standing – most notably by collaborating closely with other democratic nations, namely the U.S., India and Australia.

At the same time, Japan will try as much as possible to preserve the recent thaw in bilateral relations with China. This policy, however, will not preclude simultaneous efforts to reduce Japan’s economic dependencies on China.

The success of a “peaceful ambivalence” scenario – i.e., avoiding actions that could cause an unstoppable decline into a confrontation – depends on several factors beyond Tokyo’s control. There is the looming potential of a change in the leadership of the U.S. Also, there is the unknown of supreme leader Xi’s vision of a hegemonic China; we cannot foresee whether more chauvinistic elements within the CPC will be able to goad him toward full confrontation. One should remember that Beijing’s strongman has invested his own prestige and political future into China’s ambitious design.

Both China and Japan know that a shooting war would cause immense damage and drastically set back relations in the Far East region. History teaches that fights can break out over any rationale. Indeed, it is the Japanese empire’s fatal expansionism that some historians now see as a useful warning for China not to repeat the same mistakes.