Instability in East Asia: Trade clash between two U.S. allies

By imposing economic sanctions on South Korea, Japan establishes a dangerous precedent. At times when countries neighboring North Korea should be strengthening their ties and establishing transnational security cooperation, the conflict between Japan and South Korea could ultimately weaken the region.

In a nutshell

- Tokyo and Seoul are at each other’s throats, revoking trade privileges as the conflict escalates

- Despite integration efforts, East Asia remains a fractured region where there is no joint security system

- With less reliable U.S. involvement in the region, the Tokyo-Seoul tug-of- war could pose a serious security threat

One would think that the world, and Asia in particular, would be weary of crises and geopolitical flashpoints by now, but two allies of the United States, Japan and South Korea, are currently at each other’s throats. The trade clash between the two Northeast Asian neighbors has far-reaching implications and negatively affects security in this volatile region.

Pressure on Seoul

In July, Japan unexpectedly decided to restrict exports of certain materials of vital importance for the semiconductor industry in South Korea – one of the country’s most important manufacturing sectors. Seoul reacted vigorously and complained to the World Trade Organization (WTO). The Japanese government maintains the measures were in line with trade regulations.

Tokyo justifies its actions with the argument that these materials could become dual-use goods in North Korea and ultimately be destined to build weapon systems. Japan thus believes its export restrictions are coherent with the international sanctions in place against North Korea.

Japan believes its export restrictions are coherent with international sanctions against North Korea.

The Japanese government also took South Korea off its “white list,” thereby revoking trade privileges. In retaliation, Seoul announced that it would remove Japan from its white list. In the meantime, public opinion in South Korea turned against Japan. Protesters called on consumers to shun Japanese products. There are already signs of a marked slowdown in bilateral tourism, with the number of South Koreans traveling to Japan plunging to about half of last year’s figure. The situation is unlikely to improve soon, although Tokyo has backtracked on some export restrictions. It is worth noting that the Japanese are increasingly convinced their government is rightfully responding to unreasonable demands by South Korea.

Collateral damage

During calmer times – when enthusiasm about globalization went unchallenged – there were optimistic assessments about economic integration in the Far East. Some experts even foresaw the emergence of a common market and currency, along the lines of the unification process in Europe. However, such projections were, and remain, a fatal misjudgment of history. The evolution of the European Union rests on the twin pillars of NATO and post-World-War II French-German reconciliation. East Asia does not possess a multilateral security structure, and there has been no reconciliation between China, Japan and the Koreas.

It is important to recall that substantial damage was inflicted to East Asian security and economic integration when President Trump abrogated the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) immediately after taking office. This agreement offered significant geopolitical and economic benefits that are now badly missed in East Asia. Most notably, had the TPP been in place or in the last stages of negotiation, the Korean-Japanese trade spat we are witnessing would most likely have been avoided.

Facts & figures

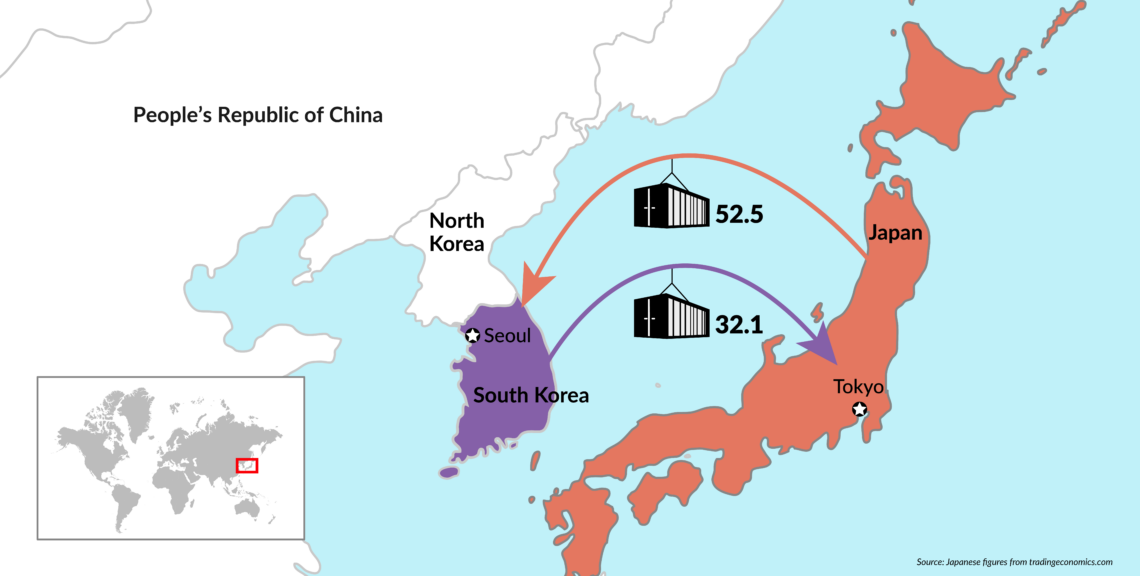

Trade between Japan and South Korea

Exports and imports in 2018 (billions of USD)

What makes the situation in East Asia particularly volatile is the lack of a regional security framework. There are various types of bilateral treaties between the United States and individual East Asian nations – the most substantial of which are with Japan and South Korea. There is a significant U.S. military presence in both countries and the bases in Okinawa are among the most critical security instruments in the world.

Yet the burden of history is never very far when it comes to Korean-Japanese relations. In 1910, long before the outbreak of the Pacific War (1941-1945), Japan annexed the Korean Peninsula as a colony. The Japanese occupation only formally came to an end with the capitulation of Tokyo in August 1945.

Pandora’s box

During the Cold War, external pressures kept a lid on open confrontations between South Korea and Japan. More recently, with Shinzo Abe becoming Prime Minister in 2012 and Moon Jae-in entering the Blue House in May 2017, the climate has become more unstable, particularly since the start of the Trump presidency in Washington. Mr. Abe steers a forceful course when it comes to national defense and security. He aims to abrogate Article 9 of the Japanese constitution, which restricts Japan’s military defense to its shores. This attitude causes considerable concerns among its neighbors, particularly China and South Korea.

The most recent souring in Japanese-Korean relations has its roots in the dark legacy of the Japanese occupation of the Korean Peninsula. In 1951, Japan and 48 other countries signed the San Francisco Peace Treaty, ending the post-World War II occupation of Japan. The treaty required that Japan recognize the independence of Korea. It also stipulated that any reparation claims should be settled through special bilateral arrangements. Normalization talks between Japan and Korea began in 1952 and, after protracted negotiations, ended in 1965 with the Treaty on Basic Relations and an attached agreement on economic cooperation.

During the Cold War, external pressures kept a lid on open confrontations between South Korea and Japan.

Following the 1965 pact, Tokyo gave Seoul $300 million in grants and $200 million in loans over 10 years. At the time, these sums were equivalent to 1.6 times South Korea’s annual national budget. The funds played an important role in the country’s economic reconstruction. In return, the South Korean government agreed to use part of the money to compensate individuals who had been subjected to forced labor during the Japanese occupation.

In 2005, during the presidency of Roh Moo Hyun (2003-2008), things began to unravel. South Korea claimed that the 1965 pact did not include compensation for all war-related hardships and that it most notably ignored the so-called “comfort women” subjected to systemic sexual abuse by Japanese soldiers.

Finally, in 2018, South Korea’s Supreme Court ruled that the 1965 pact only settled issues between the two countries, not individual compensation. Consequently, Japanese firms ought to pay damages for the mental suffering of four former wartime forced laborers. An alarmed Tokyo insisted that all claims had been settled and that the court ruling contradicted the 1965 pact. Japan feared the ruling would open a Pandora’s box of compensation claims in other countries occupied during the short-lived empire. A senior Japanese government official stated that on this issue, Japan could “not even move one millimeter.”

Trade threatened

While the short-term economic and security consequences in the region are worrying, the most disturbing issue relates to the future of free trade. In a way, Prime Minister Abe’s government is following the steps of the Trump administration. Trade is being used to score political points, thus the risk of impacting international trade and the world economy. Already, we have seen China limiting the export of rare earths, causing disruptions to international and even global supply chains.

Scenarios

There is some concern that trade policies could become the platform for a nationalist surge in East Asia – playing tit for tat by imposing tariffs on imports and restricting exports. History shows that trade restrictions are easy to implement but difficult to remove. Presently, the Japanese public is not afflicted by the trade spat between Tokyo and Seoul. However, it could be the beginning of a downward spiral toward mercantilism and protectionism. Politicians could quickly begin to call on their people to bear the costs of such policies for “the greater good of the nation.”

Of course, the military regime of North Korea is the elephant in the room. The vital threat to peace in East Asia is in Pyongyang. This situation should prod neighboring countries into strengthening their cooperation since a divided region might provoke North Korean adventurism. However, instead of a reinforced regional and transnational security cooperation, we are witnessing a falling out among parties who should be on the same side. Meanwhile, Washington is reacting haphazardly. Security experts in the U.S. administration have less say in the situation than a president with scant interest in coherent security policy, making matters more volatile.

Disturbing background

Presently, Sino-Japanese relations are on the mend. Chinese President Xi Jinping is apparently keen to reduce the number of challenges China faces at home and abroad. This posture lessens the pressure on Prime Minister Abe to repair Tokyo’s relations with Seoul.

On the other hand, Japanese companies are eager to get back to normal relations with South Korea. Facing a rapidly shrinking and aging population at home, they badly need to expand their presence overseas – all of this while dealing with restrictions in the U.S. A targeted relaxation of the restrictions on exports to South Korea could indicate that the Japanese government is listening to the domestic industry.

In the short run, the most likely scenario for East Asia appears to be growing instability. While Prime Minister Abe is firmly in power and secure at the helm of Japanese politics for the coming years, South Korean President Moon faces numerous domestic challenges. In spring 2020, South Koreans will elect a new national assembly. With the economy threatening to enter a downturn in the months to come, Mr. Moon’s political support will most likely suffer.

At the same time, the region is coming to terms with a less reliable American presence. President Trump once mentioned that the U.S. might reconsider the TPP, but nobody believes that such an ambitious undertaking will materialize soon. Tokyo has spent so much political capital on the first TPP negotiations that it is highly unlikely it will muster enough domestic support for a second try. The region will have to live with more frequent friction, both in trade and security.