Voter discontent raises hopes of Spanish opposition

Spain’s economic troubles may prompt voters to seek a change in government, but increasing political fragmentation could lead to paralysis.

In a nutshell

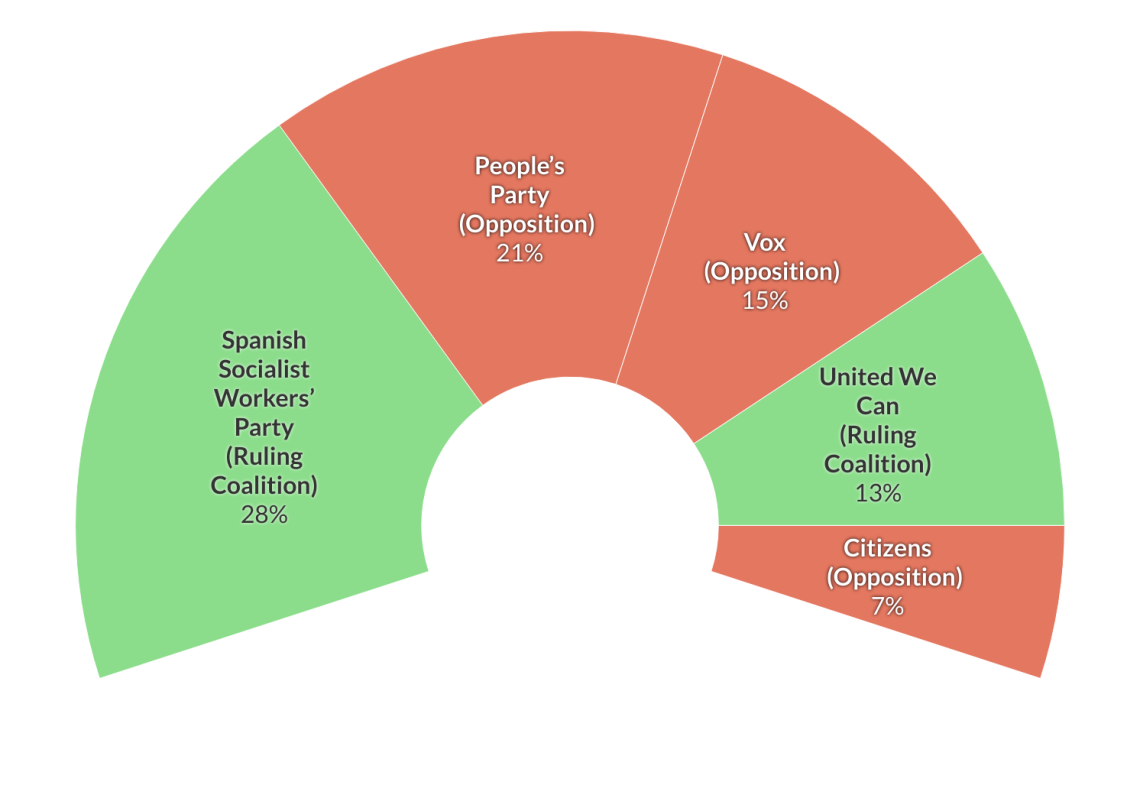

- The People’s Party and Vox, opposition forces, are poised to gain voters

- Shrinking centrism and a proliferation of parties make governing harder

- Political uncertainty will likely exacerbate the economy’s structural flaws

With a general election scheduled for December, this will be an eventful year for Spanish politics. Amid fears of recession, the erosion of consensus and clashes between the legislative and judicial powers, political instability could have serious consequences in the nation of 47 million people.

Spanish opposition forces have denounced what they call an “institutional crisis” and a “coup against the constitutional order.” Vox, a leading opposition party, is seeking a motion of censure against the government. It is a symbolic act with no chance of success since the coalition government led by Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez, leader of the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE), is supported by a parliamentary majority. The main opposition force, the conservative People’s Party (Partido Popular), is facing pressure to rally the opposition against laws adopted by the ruling coalition. But the party has declared that it will neither vote for or against the censure motion. However, the People’s Party has called for early elections, challenging the government’s legitimacy and accusing it of passing fundamental legislation opposed by voters. Failing that, voters by December 10 will elect all 350 members of the Congress of Deputies and 208 out of 265 members of the Senate in Spain’s bicameral parliament, officially called Cortes Generales.

A country of crises

Spain has been immersed in multiple crises since 2008, when the economy was among the worst hit by the great recession. By 2013, the unemployment rate exceeded 25 percent. What started as a financial crisis evolved into a social one with far-reaching political consequences, as evidenced by the emergence in 2014 of Podemos, now rebranded as United We Can. It started as a protest movement in response to rising discontent with austerity measures. In 2015, the movement turned into a progressive party led by Pablo Iglesias and secured 20.7 percent of the vote. The strong showing ended the bipartisan model – featuring the left-center Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party and the conservative People’s Party — that had characterized Spanish democracy since the 1975 death of dictator Francisco Franco.

With this new political configuration, a fresh challenge emerged in 2017 when the Catalan referendum favoring the region’s independence reignited the conflict between separatists and unionists, with political consequences beyond Catalonia. It gave rise to the anti-independentist and liberal Citizens (Ciudadanos) party and the founding and fast ascendency of the Vox nationalists.

While the end of the bipartisan system brought more political diversity, it also introduced instability. Vote fragmentation prevents the formation of majority governments and paves the way for coalitions that may erode already fragile consensus. After the April 2019 elections failed to deliver a government, regional independentist parties became determined to sustain the ruling coalition led by the socialist Mr. Sanchez, even if their share of the national vote is negligible.

In the winter of 2022, a new crisis emerged, this time triggering a collision between the legislative and judicial powers.

Read more by Teresa Nogueira Pinto

Spain reels from the pandemic and an economic downturn

Institutional crisis

The crisis was triggered by reform of the penal code, which affects the Catalonia question and the functioning of the Constitutional Court. Among the approved changes are the removal of the crime of sedition and the reduction of the sentencing for the crime of misuse of public funds, redefined to include only instances in which funds are misappropriated for personal gain. Both changes directly benefit the organizers of the 2017 referendum.

A second important aspect of this reform has to do with changes to the functioning of the Constitutional Court. In June, the mandates of four of the 12 judges had expired, thus compromising the functioning of the court. The government proposed two new appointments, and the General Council of the Judiciary had to appoint the other two judges. However, the council was also blocked, and its president resigned.

According to a recent poll, 71 percent of Spanish citizens consider the economic situation of the country to be “bad” or “very bad.’’

The leftist coalition proposed a legislative amendment altering the system of electing judges. The court, however, following an appeal by the People’s Party, ordered the suspension of the Senate vote, finding that the change was unconstitutional because it was presented as a partial amendment to a legislative bill, which was not on constitutional matters. Pressured by the European Commission, which urged all the actors to respect the rule of law, Mr. Sanchez accepted the decision of the court.

This crisis reflected the temptations of judicialization of politics or politicization of justice in times of polarization. Not surprisingly, political actors perceived it differently. For Mr. Sanchez, the unprecedented decision of the court prevented a decision from the legitimate representatives of the Spanish people. For the opposition, in turn, these legislative initiatives represented a coup against the rule of law and the constitution.

Economic determinants

But Spain’s political landscape is also a product of economic circumstances. According to a recent poll, 71 percent of Spanish citizens consider the economic situation of the country to be “bad” or “very bad,” whereas only 1.8 percent consider it to be “very good” and 7.6 percent considered it to be “good.” While this is not exclusive to Spain and it may be partially attributed to external factors like pandemic or war, these findings are bad news for the ruling coalition.

The country, whose economy never fully recovered from the 2008 crisis, is on a path to impoverishment, facing excessive debt, an untenable pension system, low productivity, relatively high youth unemployment and higher-than-expected consumer inflation.

Almost one in every three Spanish (27.8 percent) lives at risk of poverty. In the European Union, only Romania, Bulgaria and Greece have higher risks. This trend results from the erosion of the middle class and is reflected in the fact that Spain is the European country with the highest risk of poverty among adults who grew up in families with a good financial situation, and that poverty is increasing among those who have a job.

The Spanish economy has been slowing down and is expected to grow only 1.2 percent in 2023. The ruling coalition has prioritized income redistribution over economic growth by raising taxes, regulating the housing market and creating and then increasing the minimum subsistence income. While these are palliative measures, the removal of social transfers would significantly increase the number of people living in poverty.

Strategic divergences on the right and dilemmas on the left

Considering the high levels of dissatisfaction, the opposition is well-positioned to win the 2023 elections. However, parties must consider polarization and vote fragmentation. Between 2008 and 2019, the number of parties in Spain’s parliament almost doubled, from 10 to 19.

The leading opposition forces, Vox and the People’s Party, appear united in their rejection of the government, despite differences on strategic matters. They may focus less on competing against each other for votes and more on guaranteeing an alternative majority.

The 2023 general elections will likely bring a change of government, and a governing coalition including the People’s Party and Vox.

As a protest party, Vox has attracted disenchanted citizens, including voters from the impoverished working class. The party has created its own union, Solidarity (Solidaridad) and defeated PSOE in some of its strongholds. It also appeals to constituencies that feel more affected by irregular migration and young voters that challenge what they perceive as a dominant, progressive and undemocratic culture.

The party has become the most visible face of the opposition, leading several anti-government protests and being particularly vocal on issues like the unity of Spain, migration, crime or the cultural wars. A member of the new European right, Vox may be defined as an anti-globalist, sovereigntist and conservative party. Its manifesto is the “Agenda Espana,’’ designed to combat the 2030 United Nations Agenda for Sustainable Development, and focusing on food and energy sovereignty, illegal migration and cultural hegemony.

The People’s Party, in turn, is well-positioned to win centrist votes amid ongoing economic dissatisfaction and institutional instability, especially if moderate voters consider that the dominant PSOE is giving in to the radical demands of its coalition partner, United We Can. Moreover, the opposition party will likely continue to benefit from the premature erosion of the liberal Citizens Party. The victory of the People’s Party in the 2022 elections in Andalusia, a historical stronghold of the socialists, was seen as an indicator of the fragility of the PSOE. But United We Can also faces a difficult test in 2023. By joining the ruling coalition, the party has become part of the “system” that it used to denounce, losing its ability to attract discontented voters.

Facts & figures

Scenarios

Spain’s political and economic crisis reflects both wider European trends and specific national circumstances. While there are exceptions, the erosion of centrist parties has become a dominant trend in European politics. The post-Cold War period, characterized by liberal internationalism and a large, centrist consensus, is giving way to more generalized anxiety and new cleavages between sovereigntists and globalists, and conservatives and progressives over issues where finding compromise is more difficult. This new context represents a major test for liberal democracy, which depends on a common ground of fundamental values and norms regulating the political community.

Like in other European countries, political actors in Spain are adapting to this volatility, fragmentation and polarization in which coalitions become inevitable.

Three scenarios are worth considering.

Scenario 1

Under a first, most likely scenario, the 2023 general elections will bring a change of government, and a governing coalition including the People’s Party and Vox. An important indicator for this scenario will be the May municipal elections, where opposition parties are expected to have a strong performance. The People’s Party and Vox govern together in regions like Castilla y Leon, and relations between them at the national level have improved.

Under this scenario, vote fragmentation would not be negative for the center-right if it guaranteed a majority to those parties willing to form an alternative coalition. However, risks and challenges would remain, especially on issues like migration where Vox – despite its institutionalization – is expected to keep its hard line.

Such an outcome would not, per se, solve Spain’s constitutional and political crisis, which will only be overcome by the settlement of Catalonia’s status. But because it involves fundamental political claims and the very identity of Spain itself, a compromise will remain difficult to achieve.

Moreover, as the Spanish economy becomes less competitive and poverty increases, a significant strategic change – including reversing some of the measures adopted by the ruling coalition – remains unlikely, except in a scenario of a center-right victory with a stable majority. In this scenario, under which Vox would have considerable leverage, conciliation of the economic policies of both parties would be necessary. On some issues that would be possible. Both parties are committed to immediate tax cuts, less government spending (the number of civil servants has increased in recent years, reaching more than 2.7 million) and the reversal of the right to housing law, which introduces caps and freezes on rental prices and reduces ownership rights. In other issues, convergence could be more difficult. Vox has declared not only socialism, but also globalism, as the main enemies, calling for protectionist measures to defend Spain’s industry against foreign competition.

Scenario 2

A second scenario is the replication of the so-called “Ayuso model” on a national level. Through a strategy of focusing on opposition against the socialists (under the slogan “socialism or freedom”), the president of the Madrid Community, Isabel Ayuso, was able to win a majority for the People’s Party, defeat the PSOE and Pablo Iglesias, while containing Vox. However, Spain is not Madrid and, in many poorer regions, voters may feel closer to Vox. In addition, Alberto Nunez Feijoo, while considered a credible national leader of the People’s Party, may lack the charisma of Ms. Ayuso. This scenario would bring less change for two main reasons: first, because the opposition party is not expected to win a majority comfortable enough to substantially alter economic and social policies and, second, because the party has lost some of its reformist impetus since the government of Mariano Rajoy, who served as prime minister from 2011 to 2018. This outcome would, however, guarantee more stability.

Scenario 3

Under a third scenario, the results of the 2023 general elections would not allow for the formation of a government. While this is a less likely scenario, tensions between Vox and the People’s Party in Madrid, for example, expose the strategic and ideological divergences between the two parties. Political uncertainty combined with structural economic vulnerabilities would have devastating consequences for Spain, especially in the context of weak growth or even recession.