Is there a future for the Stability and Growth Pact?

As inflation rears its head after a two-decade absence and the specter of sovereign defaults returns, the European Monetary Union seems determined to throw away its fiscal anchor.

In a nutshell

- Severe shocks have forced the EU to suspend fiscal rules

- The Commission’s projects add pressure to relax curbs

- A shift to qualitative rules could wreck fiscal discipline

On May 23, 2020, the European Union suspended its fiscal rules. It was the first time this had happened since the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) was created in 1997.

The measure was exceptional, though it was justified by the exceptional circumstances of the coronavirus crisis. From one day to the next, countries had to cope with unprepared and overwhelmed public health systems while throwing a lifeline to millions of households and businesses whose livelihoods were choked off by lockdowns. With each new Covid-19 wave, the scale of financing needs increased dramatically. In such a context, requiring governments to restructure high deficits and public debt was out of the question.

How long the suspension would last, and under what conditions the rules would be reinstated, was not specified at that uncertain moment. For some time, however, January 2023 was evoked as a possible target date. The European Commission had been expected to submit a proposal in that direction in the coming weeks.

Tragic setback

Plans to reactivate the SGP were instantly compromised on February 24, when Russia invaded Ukraine. The pandemic is far from over, and already another major crisis has emerged. Once again, EU governments are struggling to decide which fiscal and monetary policies are needed to respond to this new economic shock.

The very least the EU can expect is a severe economic recession, coupled with a surge in energy prices and overall inflation.

Member states are only now starting to assess how the war might affect them in the short and medium term. There is no doubt that the new refugee crisis, along with the spillover effects of drastic sanctions against Russia, will have serious economic repercussions. Their effect will be magnified if a ban on imports of Russian oil and gas, let alone proposals of a total trade embargo, are adopted by European members of NATO and the EU, along with their allies. The very least the EU can expect is a severe economic recession, coupled with a surge in energy prices and overall inflation. Stagflation is looming. Potentially, its consequences may be far worse than anyone can imagine now.

In such a context, established policy paradigms could be thrown out the window. Is the definitive end of the SGP nearer than we thought? Has the very idea of EU fiscal rules been rendered obsolete, as many politicians and economists already claim?

Fiscal straitjacket

The current fiscal targets date back to 1992, when the Maastricht Treaty set up the original architecture for economic governance in the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU). The EMU was based on a single monetary policy, to be conducted by an independent European Central Bank (ECB) on one side, and on a set of coordinated national fiscal policies on the other. At the time, fiscal discipline was considered an indispensable prerequisite for a monetary union that did not possess a common fiscal authority or capacity.

The SGP, signed five years later, was supposed to implement the quantitative reference values for the EU’s public debt and deficit rules as defined by the Maastricht Treaty. It was stated that the annual government deficit must not exceed 3 percent of GDP, and that the general government debt must not exceed 60 percent of GDP. In the 1990s, these figures coincided with the average economic situation of the 12 countries negotiating the Treaty.

In other words, the EU’s fiscal framework was created in a context of what by today’s standards would be considered low public debt and fast economic growth. Contemporary economies have not come anywhere close to experiencing such favorable conditions for many years.

Facts & figures

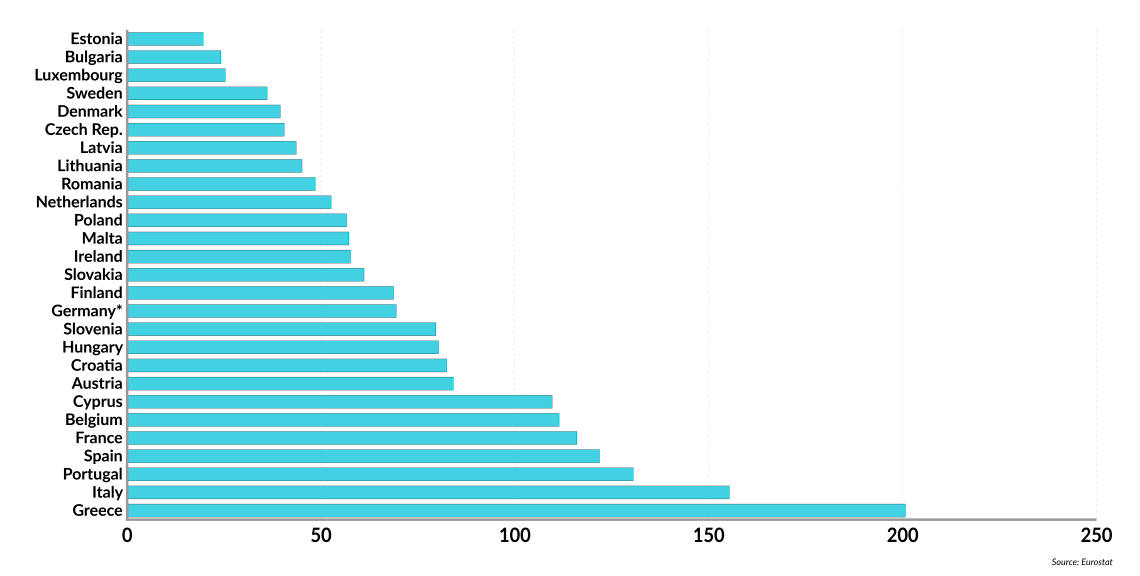

Government debt-to-GDP ratio (%)

Q3, 2021

To take the debt criterion, for example, at the end of the third quarter of 2021, the general government debt-to-GDP ratio stood at 200.7 percent for Greece, 155.3 percent for Italy, 130.5 percent for Portugal, 121.8 percent for Spain, 116 percent for France and 109.6 percent for Cyprus. For the whole euro area, the debt ratio amounted to 97.7 percent.

Debt tsunamis

As Europe faces its worst security crisis in decades, debt burdens will only increase. At the EU’s Versailles summit on March 10, member states jointly committed to massive increases in defense spending and investments in innovative technologies to become more self-sufficient in the production of food, energy and military hardware. Even in a best-case scenario, the consequences of the Russo-Ukrainian war will have a long-lasting effect on the EU. In case of a protracted war or serious escalation, the International Monetary Fund has warned that the impact could be “devastating.”

Even fiscally conservative countries such as Germany, Austria and the Netherlands, along with low-debt member states in Scandinavia and Eastern Europe, which have normally insisted on the importance of getting the bloc’s public finances on a sounder footing, have recently conceded that returning to the normal implementation of the SGP is inconceivable. None of them wants to see southern members going down the path of austerity again. The disastrous mismanagement of the Greek debt crisis and near-Grexit in 2015-2016 (sometimes dubbed “Graccident,” for an unintended Greek exit from the euro area) still very much weighs on policymakers’ minds. In hindsight, the whole episode is considered one of the EU’s biggest policy failures.

Moreover, all parties involved are worried that the EU’s fiscal framework, if reinstated, would hamper not only the bloc’s post-pandemic recovery (not to mention its unpredictable and still distant postwar recovery), but also efforts to deal with the longer-term economic challenges of climate change and aging populations.

The Commission’s plan to reinstate the SGP could indeed conflict with another one of its flagship projects presented last year – the so-called Fit for 55 package under the European Green Deal, which aims to reduce net greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55 percent by 2030, as compared to 1990 levels. The Commission estimates that funding this transition to clean energy will cost EU countries about 520-575 billion euros a year.

The new generation of fiscal rules came with its own flaws.

At the same time, aging populations will significantly worsen the fiscal outlook, as healthcare and pension expenditures are likely to explode in the coming years. Coping with these budgetary stresses all at once will require backbreaking effort and sacrifice, especially from high-debt member states still struggling to emerge from the Covid-19 recession.

So far, EU leaders seem to have fallen in line with a riff on John Maynard Keynes’ famous quip made by French economist Jean Pisani-Ferry in 2019: “When facts change, change the pact.” All agree that the current phase of pre-negotiation should serve as a useful pause to consider how the EU’s fiscal corset could be loosened. Consensus must be reached before the rules are reinstated, it is argued.

Too smart

Calls for reform are not new. The SGP has been subjected to harsh criticism since its inception. At the time, many said its one-size-fits-all framework was too rigid. The pact did not account for country specificities or allow the flexibility to respond to unforeseen circumstances. Worse, it was economically damaging. By constraining government action during crises, critics said, it contributed to making recessions longer and more severe. Moreover, rules that are too strict often end up being ignored. In 2002, then-EU Commission President Romano Prodi bluntly called Europe’s fiscal rules “stupid.”

Between 2005 and 2015, several far-reaching reforms were implemented, including two voluminous packages of regulations and directives commonly labeled six-pack and two-pack. Their purpose was to improve compliance with fiscal rules by tightening the EU’s monitoring of member states. In this context, a sophisticated framework for integrated surveillance and coordination, known as the European Semester, was created.

The new generation of fiscal rules came with its own flaws. In the blink of an eye, the rules had moved from “stupid to too smart,” a group of researchers wrote in 2018.

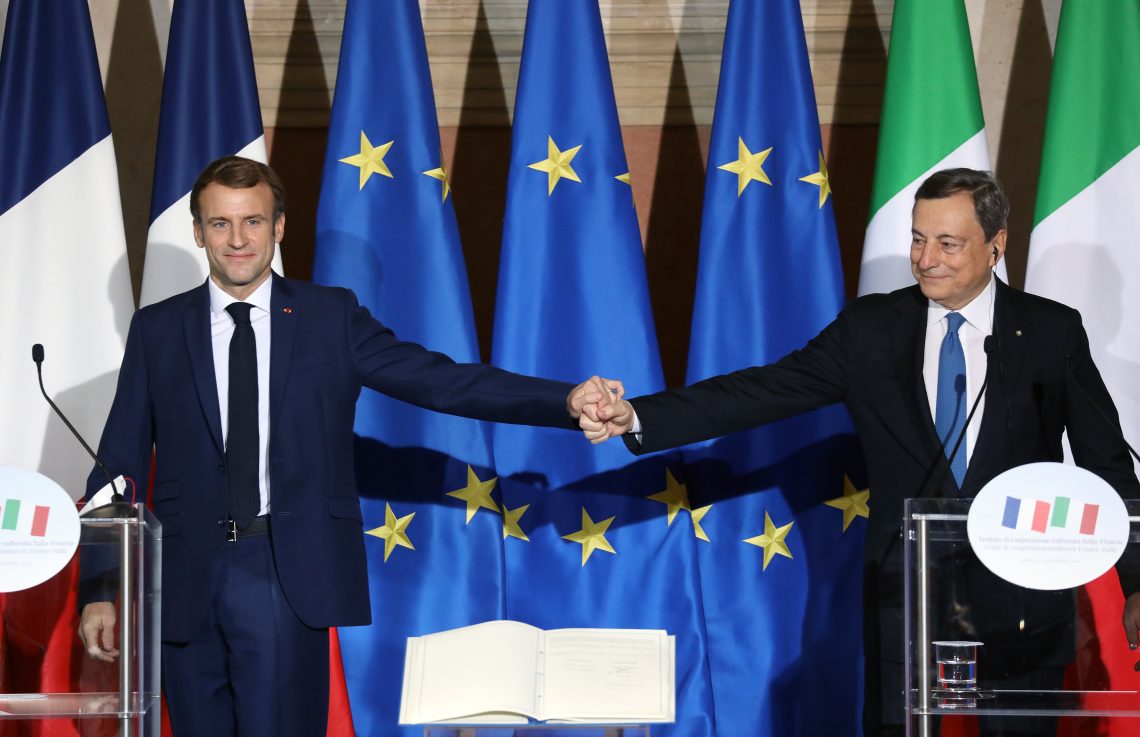

In a recent Financial Times opinion piece, French President Emmanuel Macron and Italian Prime Minister Mario Draghi complained, yet again, that the rules are “too obscure and excessively complex.” Member states find them very hard to understand, due in part to a maze of constantly revised, often conflicting and overlapping sub-rules, provisions, exemptions and indicators.

French economist Olivier Blanchard ironically compared the process of rebuilding the EU’s fiscal framework to the Cathedral of Avila. After years of amendments and reinterpretations, the SGP’s architecture had become absurdly cluttered, subject to so many changes and additions that its original structure was hardly recognizable.

Countries quickly learned how to exploit loopholes in the opaque system. Many systematically delayed fiscal adjustments, notably through “creative accounting gimmickry.” Critics also highlighted unequal treatment of member states, arguing that sanctions against noncompliers were applied unfairly. While punitive proceedings for violating EU budgetary rules were instigated against several southern member states, France and Germany were routinely spared.

In the end, though, no fines have ever been imposed on a member state for violating the SGP. That has exposed the Commission to allegations of leniency toward fiscally irresponsible governments. Some analysts saw such practices as a manifestation of the EU’s growing politicization, which resulted in a watering down of the Pact and, ultimately, the loss of its credibility.

Proposed remedies

The Funcas Europe platform recently listed a range of redesign proposals made in light of the Covid-19 pandemic. Several stand out as potential inspiration for SGP reformers.

German economist Achim Truger suggests raising the debt limit from 60 to 90 percent of GDP. The 3 percent deficit limit could also be “adjusted upward,” he argues. However, these would require a formal amendment of the Maastricht Treaty – a complex task given constant political friction between the member states.

Enrico D’Elia suggests that the fiscal rules compare the debt and deficit figures to revenue rather than GDP. A study requested by the European Parliament calls for the implementation of a “green golden rule” that would exempt capital investments on environmental projects from the debt totals. And ECB researchers, for their part, have proposed shifting the fiscal rules from sanctions for noncompliance to rewards for compliance.

For many years, this fiscal union has remained an unreachable goal. Why should it be any more attainable now?

The European Fiscal Board (EFB) insists on the importance of completing the EMU by finally building in a permanent central fiscal capacity. For many years, this Fiscal Union has remained an unreachable goal. Why should it be any more attainable now?

The EFB thinks the one-off recovery plan, NextGenerationEU, could be a step in the right direction. Embedded in a reformed EU budget, this fiscal instrument could be enlarged and made permanent, giving the bloc an ability to respond swiftly to severe shocks such as we are experiencing now or to implement high-priority common investments, such as green energy or defense projects.

All of these proposals agree on one point: the EU’s fiscal rules need to be simplified.

Rules vs. discretion

However, the aforementioned Mr. Blanchard, also a former IMF chief economist, believes it is an illusion to think that such fiscal rules can be “simple.” He adds that it is just as delusional to believe they can ever be “complex enough” to encompass contemporary economic reality.

Together with coauthors Alvaro Leandro and Jeromin Zettelmeyer, Mr. Blanchard has presented various versions of a research paper (whose latest iteration was published in October 2021) containing his own modest proposal: that quantitative fiscal “rules” be abandoned altogether in favor of “qualitative prescriptions” or “standards” that “leave room for judgment.”

For example, it could be stated that “member states shall ensure that their public debts remain sustainable with high probability.” In other words, in assessing a country’s effort to maintain fiscal discipline, what should count are not statistical benchmarks such as debt-to-GDP ratios but rather “qualitative standards” that distinguish good from bad behavior and focus more on debt trajectories and sustainability.

How such “standards” would be enforced without opening the door to discretionary excesses remains an open question.

Like the other proposals, Mr. Blanchard’s is built on the assumption that the low interest rate environment we have known for many years will persist for “some time to come.” As long as borrowing costs stay close to zero, he believes, excessive debt would not represent an intolerable threat.

A very different picture emerges, however, if one envisages an environment of steeply rising public debt, sluggish economic growth and higher interest rates. This has become today’s baseline scenario. Indeed, the ECB is expected to start a monetary tightening cycle by the end of this year. And Economy Commissioner Paolo Gentiloni recently warned that fiscal rules limiting government borrowing could remain suspended until at least the end of 2023.

These decisions might be wise in the current context. But the downside is that the specter of sovereign defaults will loom into view sooner rather than later. This makes it once again clear that without an effective framework for fostering fiscal discipline, the EMU is simply unviable.